Elon Musk might be understandably impressed with China’s ubiquitous super-app WeChat, but the truth is there are many corners of the Chinese internet that even the popular app hasn’t explored.

Take, for instance, the landscape of online religious worship, which has flourished over the past few years. In 2021, China’s internet users surpassed 1 billion, and the Covid-19 pandemic pushed many offline activities into the online realm.

Chinese practitioners of multiple religions, such as Buddhism, Daoism, and Islam, are taking their faith to domestic instant messaging apps, blogs, microblogs, ecommerce sites, and social media platforms, and the results are otherworldly, to say the least.

Examples of Buddhism-inspired content on Douyin

For instance, chanting Buddhist sutras in the middle of your day just got a lot more convenient. Instead of trekking to your nearest temple, download the app ‘Digital Wooden Fish’ (电子木鱼) — named after muyu (木鱼) or fish-shaped wooden gongs — to start a prayer session on your mobile phone.

The interactive app, which will broadcast sutras for you to chant along to, even lets you play the gong by tapping on the screen.

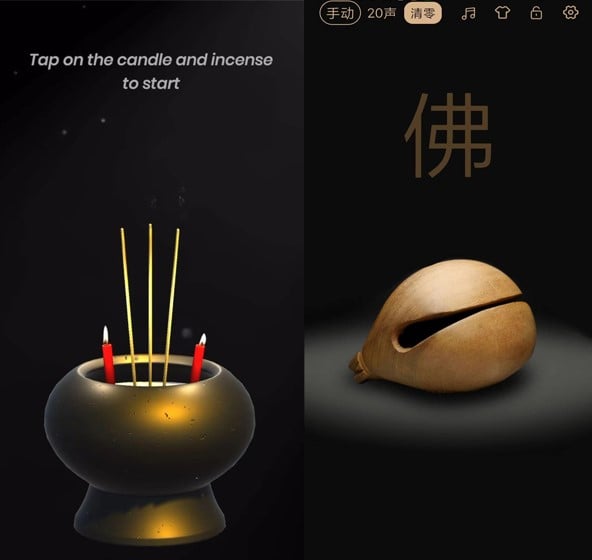

Screenshots from the Mobile Incense app and Digital Wooden Fish app

Each tap increases the user’s ‘good virtue score’ (功德值, gongde zhi), which can be accumulated and shared with friends on popular Chinese social media platforms, such as WeChat, Weibo, and Xiaohongshu.

Meanwhile, another prayer app called ‘Mobile Incense’ allows users to burn digital incense.

Religious netizens searching for more interactive experiences should head to the Chinese video platform Bilibili. The website is flooded with an endless stream of sacred (and sometimes profane) content, including monks engaging in mukbang or carrying out live looping sets and hours-long sutras in multiple languages like Mandarin, Tibetan, and Sanskrit.

Bilibili is also where RADII has discovered one of the most exciting yet bizarre forms of cyber worship: bullet chat prayers.

Bullet comments (弹幕, danmu), which allow viewers to send live comments flying across the screen during a video, are prevalent on China’s numerous streaming platforms.

The content of the comments is entirely user-generated and varies greatly depending on the context. Some in China use this function to banter about content and control avatars while online clubbing, while others use it to pray or request blessings from deities on sutra-chanting videos.

On-screen during one video, a concerned grandparent pleaded, “Buddha, please bless my granddaughter and allow her to pass both subjects of her art examinations,” while a more cynical netizen typed, “Buddha, please make my school explode.” (Yikes!)

Whether or not online worship is effective remains hard to prove. Still, it seems likely that the phenomenon will continue to evolve (metaverse churches are already a thing) and influence religious practices.

Cover image via Bilibili

FUTURE

Digital Incense and Cyber Chants: Religion Goes Online in China

Beatrice Tamagno

2 mins read

Beatrice Tamagno

2 mins read

Elon Musk might be understandably impressed with China’s ubiquitous super-app WeChat, but the truth is there are many corners of the Chinese internet that even the popular app hasn’t explored.

Take, for instance, the landscape of online religious worship, which has flourished over the past few years. In 2021, China’s internet users surpassed 1 billion, and the Covid-19 pandemic pushed many offline activities into the online realm.

Chinese practitioners of multiple religions, such as Buddhism, Daoism, and Islam, are taking their faith to domestic instant messaging apps, blogs, microblogs, ecommerce sites, and social media platforms, and the results are otherworldly, to say the least.

For instance, chanting Buddhist sutras in the middle of your day just got a lot more convenient. Instead of trekking to your nearest temple, download the app ‘Digital Wooden Fish’ (电子木鱼) — named after muyu (木鱼) or fish-shaped wooden gongs — to start a prayer session on your mobile phone.

The interactive app, which will broadcast sutras for you to chant along to, even lets you play the gong by tapping on the screen.

Each tap increases the user’s ‘good virtue score’ (功德值, gongde zhi), which can be accumulated and shared with friends on popular Chinese social media platforms, such as WeChat, Weibo, and Xiaohongshu.

Meanwhile, another prayer app called ‘Mobile Incense’ allows users to burn digital incense.

Religious netizens searching for more interactive experiences should head to the Chinese video platform Bilibili. The website is flooded with an endless stream of sacred (and sometimes profane) content, including monks engaging in mukbang or carrying out live looping sets and hours-long sutras in multiple languages like Mandarin, Tibetan, and Sanskrit.

Bilibili is also where RADII has discovered one of the most exciting yet bizarre forms of cyber worship: bullet chat prayers.

Bullet comments (弹幕, danmu), which allow viewers to send live comments flying across the screen during a video, are prevalent on China’s numerous streaming platforms.

The content of the comments is entirely user-generated and varies greatly depending on the context. Some in China use this function to banter about content and control avatars while online clubbing, while others use it to pray or request blessings from deities on sutra-chanting videos.

On-screen during one video, a concerned grandparent pleaded, “Buddha, please bless my granddaughter and allow her to pass both subjects of her art examinations,” while a more cynical netizen typed, “Buddha, please make my school explode.” (Yikes!)

Whether or not online worship is effective remains hard to prove. Still, it seems likely that the phenomenon will continue to evolve (metaverse churches are already a thing) and influence religious practices.

Cover image via Bilibili

NEWSLETTER

Get weekly top picks and exclusive, newsletter only content delivered straight to you inbox.

NEWSLETTER

Get weekly top picks and exclusive, newsletter only content delivered straight to you inbox.

RADII NEWSLETTER

Get weekly top picks and exclusive, newsletter only content delivered straight to you inbox

RELATED

Dakka App: the Indie Café Hunter’s Secret Weapon in Hong Kong

China Cracks Down on OnlyFans to Push its Digital Social Stability Further

Shopping Made Even Easier Through RedNote x Taobao x Tmall Partnership

Digital Incense and Cyber Chants: Religion Goes Online in China

Beatrice Tamagno

2 mins read

Elon Musk might be understandably impressed with China’s ubiquitous super-app WeChat, but the truth is there are many corners of the Chinese internet that even the popular app hasn’t explored.

Take, for instance, the landscape of online religious worship, which has flourished over the past few years. In 2021, China’s internet users surpassed 1 billion, and the Covid-19 pandemic pushed many offline activities into the online realm.

Chinese practitioners of multiple religions, such as Buddhism, Daoism, and Islam, are taking their faith to domestic instant messaging apps, blogs, microblogs, ecommerce sites, and social media platforms, and the results are otherworldly, to say the least.

For instance, chanting Buddhist sutras in the middle of your day just got a lot more convenient. Instead of trekking to your nearest temple, download the app ‘Digital Wooden Fish’ (电子木鱼) — named after muyu (木鱼) or fish-shaped wooden gongs — to start a prayer session on your mobile phone.

The interactive app, which will broadcast sutras for you to chant along to, even lets you play the gong by tapping on the screen.

Each tap increases the user’s ‘good virtue score’ (功德值, gongde zhi), which can be accumulated and shared with friends on popular Chinese social media platforms, such as WeChat, Weibo, and Xiaohongshu.

Meanwhile, another prayer app called ‘Mobile Incense’ allows users to burn digital incense.

Religious netizens searching for more interactive experiences should head to the Chinese video platform Bilibili. The website is flooded with an endless stream of sacred (and sometimes profane) content, including monks engaging in mukbang or carrying out live looping sets and hours-long sutras in multiple languages like Mandarin, Tibetan, and Sanskrit.

Bilibili is also where RADII has discovered one of the most exciting yet bizarre forms of cyber worship: bullet chat prayers.

Bullet comments (弹幕, danmu), which allow viewers to send live comments flying across the screen during a video, are prevalent on China’s numerous streaming platforms.

The content of the comments is entirely user-generated and varies greatly depending on the context. Some in China use this function to banter about content and control avatars while online clubbing, while others use it to pray or request blessings from deities on sutra-chanting videos.

On-screen during one video, a concerned grandparent pleaded, “Buddha, please bless my granddaughter and allow her to pass both subjects of her art examinations,” while a more cynical netizen typed, “Buddha, please make my school explode.” (Yikes!)

Whether or not online worship is effective remains hard to prove. Still, it seems likely that the phenomenon will continue to evolve (metaverse churches are already a thing) and influence religious practices.

Cover image via Bilibili

NEWSLETTER

Get weekly top picks and exclusive, newsletter only content delivered straight to you inbox.

RADII NEWSLETTER

Get weekly top picks and exclusive, newsletter only content delivered straight to you inbox

RELATED POSTS

FUTURE

Digital Incense and Cyber Chants: Religion Goes Online in China

Beatrice Tamagno

2 mins read

Beatrice Tamagno

2 mins read

Elon Musk might be understandably impressed with China’s ubiquitous super-app WeChat, but the truth is there are many corners of the Chinese internet that even the popular app hasn’t explored.

Take, for instance, the landscape of online religious worship, which has flourished over the past few years. In 2021, China’s internet users surpassed 1 billion, and the Covid-19 pandemic pushed many offline activities into the online realm.

Chinese practitioners of multiple religions, such as Buddhism, Daoism, and Islam, are taking their faith to domestic instant messaging apps, blogs, microblogs, ecommerce sites, and social media platforms, and the results are otherworldly, to say the least.

For instance, chanting Buddhist sutras in the middle of your day just got a lot more convenient. Instead of trekking to your nearest temple, download the app ‘Digital Wooden Fish’ (电子木鱼) — named after muyu (木鱼) or fish-shaped wooden gongs — to start a prayer session on your mobile phone.

The interactive app, which will broadcast sutras for you to chant along to, even lets you play the gong by tapping on the screen.

Each tap increases the user’s ‘good virtue score’ (功德值, gongde zhi), which can be accumulated and shared with friends on popular Chinese social media platforms, such as WeChat, Weibo, and Xiaohongshu.

Meanwhile, another prayer app called ‘Mobile Incense’ allows users to burn digital incense.

Religious netizens searching for more interactive experiences should head to the Chinese video platform Bilibili. The website is flooded with an endless stream of sacred (and sometimes profane) content, including monks engaging in mukbang or carrying out live looping sets and hours-long sutras in multiple languages like Mandarin, Tibetan, and Sanskrit.

Bilibili is also where RADII has discovered one of the most exciting yet bizarre forms of cyber worship: bullet chat prayers.

Bullet comments (弹幕, danmu), which allow viewers to send live comments flying across the screen during a video, are prevalent on China’s numerous streaming platforms.

The content of the comments is entirely user-generated and varies greatly depending on the context. Some in China use this function to banter about content and control avatars while online clubbing, while others use it to pray or request blessings from deities on sutra-chanting videos.

On-screen during one video, a concerned grandparent pleaded, “Buddha, please bless my granddaughter and allow her to pass both subjects of her art examinations,” while a more cynical netizen typed, “Buddha, please make my school explode.” (Yikes!)

Whether or not online worship is effective remains hard to prove. Still, it seems likely that the phenomenon will continue to evolve (metaverse churches are already a thing) and influence religious practices.

Cover image via Bilibili

NEWSLETTER

Get weekly top picks and exclusive, newsletter only content delivered straight to you inbox.

NEWSLETTER

Get weekly top picks and exclusive, newsletter only content delivered straight to you inbox.

RADII NEWSLETTER

Get weekly top picks and exclusive, newsletter only content delivered straight to you inbox

RELATED

Dakka App: the Indie Café Hunter’s Secret Weapon in Hong Kong

China Cracks Down on OnlyFans to Push its Digital Social Stability Further

Shopping Made Even Easier Through RedNote x Taobao x Tmall Partnership

Digital Incense and Cyber Chants: Religion Goes Online in China

Beatrice Tamagno

2 mins read

Elon Musk might be understandably impressed with China’s ubiquitous super-app WeChat, but the truth is there are many corners of the Chinese internet that even the popular app hasn’t explored.

Take, for instance, the landscape of online religious worship, which has flourished over the past few years. In 2021, China’s internet users surpassed 1 billion, and the Covid-19 pandemic pushed many offline activities into the online realm.

Chinese practitioners of multiple religions, such as Buddhism, Daoism, and Islam, are taking their faith to domestic instant messaging apps, blogs, microblogs, ecommerce sites, and social media platforms, and the results are otherworldly, to say the least.

For instance, chanting Buddhist sutras in the middle of your day just got a lot more convenient. Instead of trekking to your nearest temple, download the app ‘Digital Wooden Fish’ (电子木鱼) — named after muyu (木鱼) or fish-shaped wooden gongs — to start a prayer session on your mobile phone.

The interactive app, which will broadcast sutras for you to chant along to, even lets you play the gong by tapping on the screen.

Each tap increases the user’s ‘good virtue score’ (功德值, gongde zhi), which can be accumulated and shared with friends on popular Chinese social media platforms, such as WeChat, Weibo, and Xiaohongshu.

Meanwhile, another prayer app called ‘Mobile Incense’ allows users to burn digital incense.

Religious netizens searching for more interactive experiences should head to the Chinese video platform Bilibili. The website is flooded with an endless stream of sacred (and sometimes profane) content, including monks engaging in mukbang or carrying out live looping sets and hours-long sutras in multiple languages like Mandarin, Tibetan, and Sanskrit.

Bilibili is also where RADII has discovered one of the most exciting yet bizarre forms of cyber worship: bullet chat prayers.

Bullet comments (弹幕, danmu), which allow viewers to send live comments flying across the screen during a video, are prevalent on China’s numerous streaming platforms.

The content of the comments is entirely user-generated and varies greatly depending on the context. Some in China use this function to banter about content and control avatars while online clubbing, while others use it to pray or request blessings from deities on sutra-chanting videos.

On-screen during one video, a concerned grandparent pleaded, “Buddha, please bless my granddaughter and allow her to pass both subjects of her art examinations,” while a more cynical netizen typed, “Buddha, please make my school explode.” (Yikes!)

Whether or not online worship is effective remains hard to prove. Still, it seems likely that the phenomenon will continue to evolve (metaverse churches are already a thing) and influence religious practices.

Cover image via Bilibili

NEWSLETTER

Get weekly top picks and exclusive, newsletter only content delivered straight to you inbox.

RADII NEWSLETTER

Get weekly top picks and exclusive, newsletter only content delivered straight to you inbox

RELATED POSTS