On July 6, the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) announced a rigid and unprecedented rule that would force international students at schools that offer fully online courses for the fall semester to leave the country, or to transfer to other schools with in-person instruction. Harvard and MIT were among the first universities to sue the administration, and within days, a total of 60 universities from 17 states — as well as students themselves — had filed lawsuits against the “cruel, abrupt, and unlawful” legislation.

The Trump administration then redacted its announcement on July 14, shortly before a federal judge in Boston was to hear arguments for the lawsuit that was filed by Harvard and MIT against the rule.

This redaction has caused an immediate stir in China, which has an estimated 370,000 students currently studying abroad in the US. The hashtag “US government agrees to withdraw the new student visa rules” (#美国政府同意撤销留学生签证新规#) received over 290 million views on Chinese microblogging platform Weibo in just a few hours after the news came out. Not surprisingly, the overall sentiment is confusion and anger over the changing policy, as well empathy towards the affected students.

A Hostile Environment

In a related post, one of the most-liked comments reads: “The law is not the same between morning and night. This government has lost all trust.”

Some students had already been barred from entering the country at US airports by customs officials since the ban came into effect last week. According to CNN, the government may also still be considering applying this rule to incoming new students who are currently not in the US.

The one-size-fits-all student ban is seen as a way for the Trump administration to pressure schools into reopening in the fall, according to major media outlets such as the New York Times. But for Chinese students, tension has been building for far longer — and has shaped how they now see their future in the education system they’ve enrolled in.

“I still feel extremely unwelcome in this country,” says Li Renjie, a fourth-degree doctoral student majoring in semiconductor engineering at UCLA. “When I first came to the US four years ago, it was never like this. The back and forth has really put international students in an awkward place. I feel the current administration doesn’t care about international students at all, given they could come up with this kind of abrupt and inconsiderate policy in the first place.”

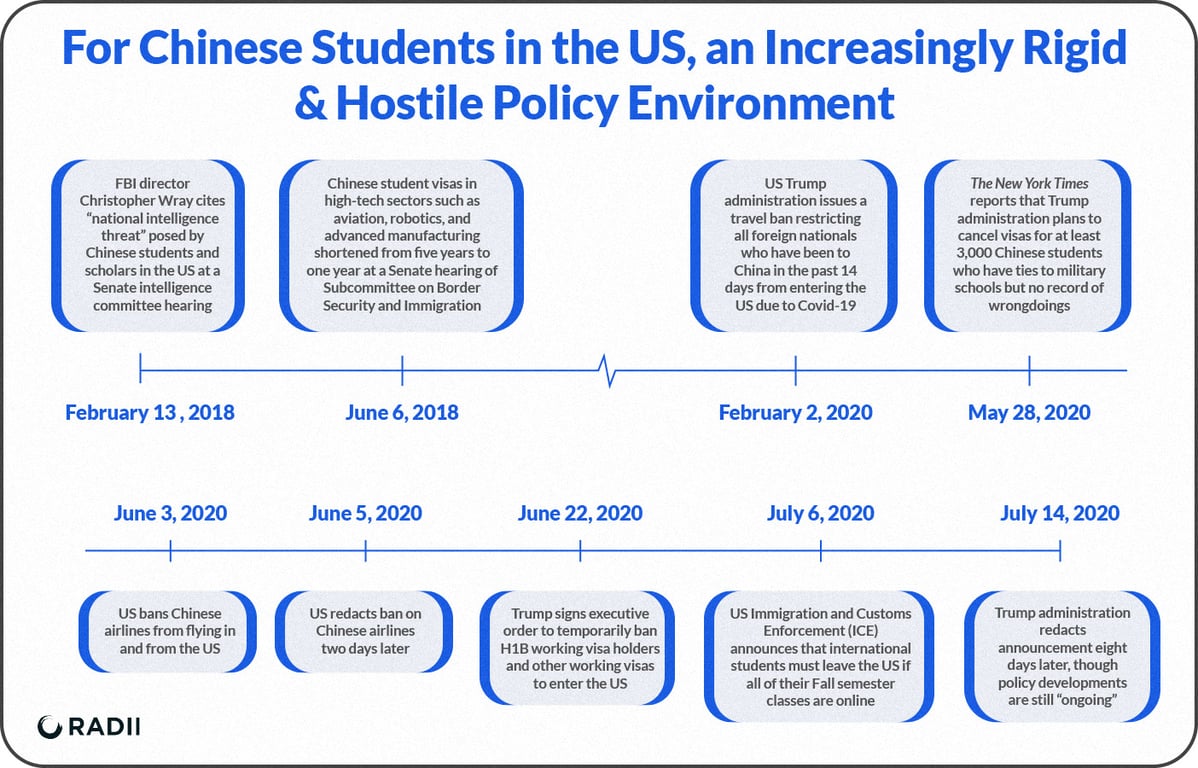

The now-rescinded rule had come after Trump temporarily froze H1B and other working visas, limited certain groups of Chinese students from entering and/or studying in the US, and issued a travel ban to restrict travellers from China in the wake of the coronavirus outbreak — moves that have caused a rollercoaster of emotions for international students over the last few months. In addition, a rise in racist and xenophobic incidents against people of Asian descent has made their learning environment potentially more hostile than ever.

Related:

A New Site to Report Racist Attacks Against Asian-Americans Received 1,000+ in Two WeeksPlus online hate speech directed at Chinese is up 900%, and there’s a growing list of incidents on Wikipedia from 38 countriesArticle Apr 06, 2020

A New Site to Report Racist Attacks Against Asian-Americans Received 1,000+ in Two WeeksPlus online hate speech directed at Chinese is up 900%, and there’s a growing list of incidents on Wikipedia from 38 countriesArticle Apr 06, 2020

Li adds that he is especially stressed because his lab research has been on hold due to the Covid-19 pandemic, which delayed his graduation date an additional year. “Even though I will not be deported anymore, I feel my future is still uncertain since my lab is closed,” he says. “I am worried about the future developments of relevant policies.”

A chart circulated among overseas Chinese students in the wake of the initial ICE announcement outlines the options that students would have after the ban:

Original image: Weibo

No matter which category they belong to, the roads were filled with dead ends: students would still need to pay high tuition fees all while facing unprecedented difficulties in booking airlines, obtaining visas, graduating, and securing job opportunities after graduation.

International Students in American Society

Economically speaking, the one million international students at US colleges and universities contributed nearly 41 billion USD to the US economy for the academic year 2018-2019, according to NAFSA statistics. Students from China make up nearly 34% of these international students — the largest group total.

International students usually pay two to three times higher tuition fees than their American counterparts. Though American universities have been called out for suing the current administration largely to preserve their economic interests, financial contributions from international students are essential to funding academic research and scholarships.

Restricting international students could also result in a reverse brain drain across many sectors, as students that remain to work represent a sizeable intellectual workforce in the US. In Silicon Valley, Asians are the largest ethnic group and are expected to make up 43.5% of the region in 2040; many of these important workers first came to the US for schooling and stayed on.

A notable early example of this is Qian Xuesen, a rocket scientist from China who graduated from Caltech with a doctorate degree and became a key researcher in the US’s Manhattan Project during World War II, playing a significant role in the early development of rocket and jet propulsion technology. In a perhaps unsurprising parallel to modern times, Qian was forced to go back to China over wrongful national security concerns in 1955.

Related:

It’s Not Rocket Science, Except When it is: The Strange Case of Qian XuesenArticle Aug 15, 2018

It’s Not Rocket Science, Except When it is: The Strange Case of Qian XuesenArticle Aug 15, 2018

Many students were also greatly impacted by their time in the US, and have sought ways to give back to their country of residence, especially during the pandemic. When cases first began to skyrocket in the US, first- and second-generation Chinese students and graduates utilized their bilateral resources to reroute PPE from Chinese factories to the then-hardest-hit states such as New York. One volunteer group made up of 13 Chinese and Chinese American friends connected 50 donor companies with suppliers and facilitated the donation of nearly 1.56 million USD-worth of supplies. First-generation Asian-Americans are also among the medical workers putting their lives at risk in the battle against Covid-19.

International students are an integral part of the American campus, and have fostered both the diversity as well as the academic competitiveness of universities. Creating an inclusive and welcoming environment for students from all kinds of backgrounds is at the heart of American core values, and on the forefront of the agenda for higher education.

“One of the reasons that I chose UCLA is because of its diverse student body. I wanted to meet interesting people from all over the world,” says Daniel Coltellaro, who grew up in California and graduated from UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs in 2018. “I had a great time meeting friends from [countries such as] China [and] Japan. Looking back, that was one of the most important decisions I have made.”

Coltellaro is planning to take the foreign service test in the hopes of becoming a diplomat in the near future. “My interactions with my international friends enriched my understanding of what’s happening outside of the US — especially China, which I used to rely on mainstream media to get relevant news about that was often biased and negative,” he says. “I think it’s crucial to welcome international students. Otherwise we just become an echo chamber that has no outside perspective, and we become stagnant.”

As US-China relations deteriorate especially at the governmental level, cultural and individual exchanges are in many ways the best diplomacy the two countries can have right now. However, the policy environment surrounding international students, especially Chinese students in the US, has become increasingly more rigid and hostile in the past two years.

Following FBI director Christopher Wray’s 2018 comments about Chinese students and scholars posing a threat to national security, there was a surge in racial profiling targeting Chinese and Chinese Americans, especially in the fields of science, academia, business, and public policy, with reportedly more intense scrutiny and discriminatory treatment against them. While real espionage cases do exist, targeting an entire ethnic group for them will only fuel prejudice, racism and hostility.

With these policies in place, there is a cooling effect for some Chinese students who wish to go to study in the US, as more and more turn to schools in European countries or simply decide to stay at home and opt for a top Chinese institution instead. According to a report (link in Chinese) by China’s largest educational service group New Oriental, the percentage of respondents who ranked the US as their number one choice for studying abroad dropped from 51% in 2015 to 43% in 2019; meanwhile, respondents who selected the UK as their top destination increased from 32% to 41% within the same time span.

Staying Hopeful

Polly Cui, a H1B employment visa holder who was working in New York City for over 2 years and has been stuck in Beijing since January, is among many who have been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and the policies it has triggered. “I graduated from NYU a few years ago and had been working in New York since then. I came back to China to visit my family during Spring Festival, then Covid happened,” she says. “Now it’s already July and I’m still here in China, not being able to return to the States because my passport is still stuck at the US consulate. I had to give up my place in the US because I can’t keep paying for an empty apartment. I also had to reschedule my flight and work remotely with time differences.”

Yet Cui remains hopeful of a return to New York. “I love the city so much — its diversity, passion and freedom [allows me] to be the wildest and weirdest version of myself. New Yorkers are all dream chasers, go getters, and warriors who are fighting for the future.”

However, she thinks students are a group that should be exempt from politically-motivated policies. “[International] students are among the most vulnerable communities,” she says, referring to the tough visa constraints, as well as job and financial pressures that they face. “Fair, human, and creative methods are needed to combat global crises like this pandemic.”

Header image: Anthony Delanoix via Unsplash