If you’ve ever wished you could take a month off and get away from it all — try giving birth in China. Today, regulated mega-spas — called “yuezi centers” (yuezi zhongxin 月子中心) — are a fast-rising trend, taking care of new moms (and their newborns) who still subscribe to traditional Chinese medicinal beliefs.

Zuo yuezi (坐月子) or “sitting the month,” refers to the month-long period of postpartum confinement traditionally practiced in China. Although these age-old conventions may sound like a punishment to modern ears, the practice was originally intended to help women recover after the strain of giving birth, though it also has its roots in how women were perceived in early Chinese society.

Related:

Why China’s New Mothers Look to Both Science and SuperstitionArticle Aug 31, 2017

Why China’s New Mothers Look to Both Science and SuperstitionArticle Aug 31, 2017

Though China gained wider access to medicine in the 20th century, traditional medicine ideas were often still practiced. Fast forward to modern day, and hygienic luxurious centers have rapidly cropped up — in 2018, there were close to 3,000 centers around China — to meet the needs of mainly middle-class women looking to get their body back on their own terms — and grapple with the challenges of modern parenting.

Getting a massage from one of the center’s nurses

I consider myself like many post ’80s and ’90s-born Chinese who inherited traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) from their parents’ and grandparents’ generation, but only practice it when convenient. So naturally when I gave birth to my first child, I didn’t exactly follow all the rules. I took a warm shower the day after I gave birth, and was dining out with friends within a week. However, once I moved into the Aidigong Yuezi Center (爱帝宫月子中心) in Shenzhen, I was forced to follow far more rules than I expected. This included wearing long sleeves, wearing socks, drinking herbal water, bathing with ginger water, and getting aijiu (艾灸, a kind of Chinese herbal aromatherapy) to ease a stiff shoulder I’d developed since giving birth.

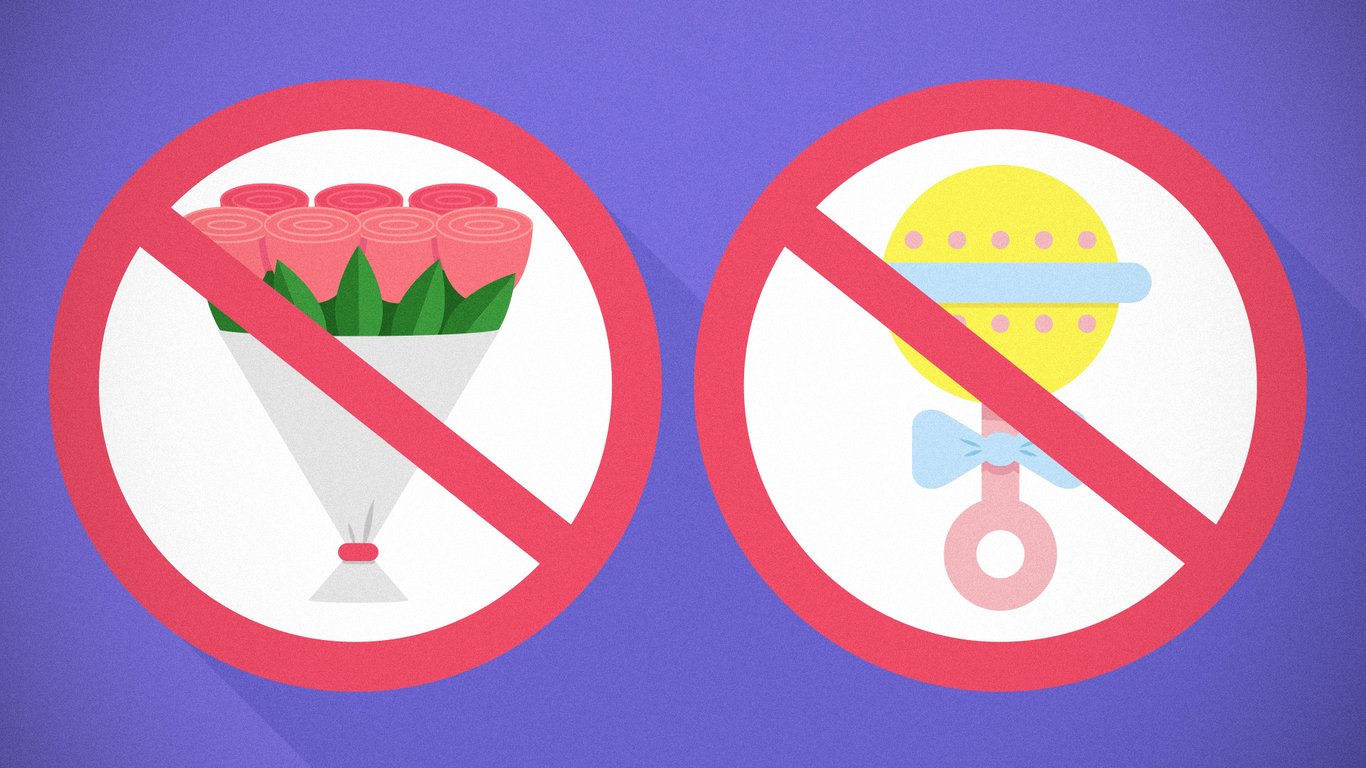

But many mothers that I spoke to at the center had the opposite problem. Yan, 32, a mother from Shenzhen that I met during my month there, was at her wits’ end dealing with her mother-in-law, who she felt had more archaic ideas about what it meant to raise a newborn and heal her “broken body.”

“I was ordered [by her] not to get out of bed,” she recalls, adding that her mother-in-law gave her further restrictions on things like showering, brushing her teeth, and turning on the air conditioning — all traditionally adhered to during the postpartum confinement period. In traditional Chinese culture, married women are typically taken care of by their mothers-in-law after giving birth, but women like Yan are often turning to these centers to get care without the generational clash. In extreme cases, the clash has sometimes led to untimely deaths, such as in 2017 when a woman in Shandong died from heatstroke (link in Chinese).

Yan recalls:

“It was unbearable. My emotions were out of control. Seeing my crying baby, I really thought about running away.”

Jia, 35, says that she and her husband wanted to learn what she and many other mothers call “science-based child rearing.” She similarly had clashes with her mother, who she says would put too many clothes on the baby and sometimes burn incense whenever the baby cried.

By enrolling in a yuezi center, and having a nurse on call to oversee them, Jia says that she felt more at ease than when she was on her own. “I read a lot of online articles beforehand,” she says, “but online experts can’t help you in daily life.”

Most of these postpartum centers are located in first- and second-tier cities, where a majority of China’s big business is concentrated and the pace of life can be relatively quick. By comparison, a day in this type of spa can feel like a vacation.

Though the centers may vary slightly, you might wake up when the baby does, and the day to follow mostly revolves around three aspects. True to TCM theory, the morning begins with treatments aimed at helping women’s bodies recuperate and lose baby weight. These treatments often run off the basis of regulating the flow of qi in your body — keeping you warm, but not overheated, is one part of that — and relieving the “blockages” that may have built up within the meridians.

Two-in-one spa treatment

Staff may also whisk away the baby at your request for treatments, baths, swimming lessons, sunbathing, massage, and even baby face masks.

Though perhaps not adhered to as strongly as some people’s in-laws would like, TCM is nevertheless present throughout the entire experience, from treatments to the medical advice to the food — pricey items such as pig’s kidneys, dates, and papaya with bird’s nest are all foods TCM theory prescribes to new moms during yuezi. Peppered throughout are a rotating schedule of monthly classes, which blend Western medicine and TCM — lessons for new moms (and often their partners) on recognizing child illnesses, educational baby games, and how to otherwise take care of their bodies and their infant after they leave the center.

A nurse plays with black and white infant cards

It’s no surprise that yuezi centers are projected to become a 30 billion RMB industry by 2025. These centers are costly; month-long stays at these centers start at around 15,000 RMB (around 2,140 USD) — well over the average monthly salary in China’s first-tier cities, according to official data — and top out at a staggering 460,000 RMB (65,000 USD) for a top-tier package in Shenzhen, according to DT Financial (link in Chinese).

But it’s an expense that more and more new moms are willing to bear. In a 2017 study, 95% of those surveyed were open to the idea of postpartum confinement, and 51% of them said they would consider enrolling in a yuezi center, up from 38% in 2014. Now China’s most popular centers are booked out as much as six months in advance, which means new parents need to make reservations as soon as their first trimester — sort of like a swanky hotel, except that your check-in date is contingent on the day you give birth.

Aside from the price tag — which is indeed hefty — I definitely found more pros than cons to this experience, regardless of whether or not one subscribes to TCM beliefs. After our month was up, I left feeling educated, emotionally supported, and crucially, well rested (it turns out, no sleepless nights for the first month of having a baby makes a huge difference for your well-being). One unexpected benefit was also the social aspect: being able to meet other new moms who were facing similar challenges and fears to my own.

Related:

Why China’s Millennials Are at War with Marriage and Having BabiesPost-‘90s millennials online are saying, “death to the next generation”Article Sep 11, 2019

Why China’s Millennials Are at War with Marriage and Having BabiesPost-‘90s millennials online are saying, “death to the next generation”Article Sep 11, 2019

And perhaps most importantly of all, it gives Mom a rare chance to have “me time” outside of her new role and cope with the changes in her life; one thing I feel these centers in China do right is prioritizing moms’ wellbeing as much as their babies. At the end of our month-long stay, both mother and baby departed for the real world healthy, and in mom’s case, ready to take on the challenges of this new stage of life.

All photos unless otherwise stated: Chaai Wu

Header image: Mayura Jain