Two guys, dressed as if they were the Chinese cast of The Book of Mormon, promoting an independent LGBTQ+ magazine called Missionary. They had me at “missionary,” and they’re gonna have you, too.

Missionary magazine is an independent publication focused on LGBTQ+ communities in China and elsewhere, created by Beijing-based visual arts organization DaddyGreenBASEMENT. They published the first issue, Public, in September last year, showcasing a series of personal discussions about male homosexuality in public spaces.

Co-founders Zhu Zhaokang (aka Dimethicone) and Yu Shiyuan (aka Blackmustard) spread their gospel to Shanghai with an appearance at the Art Book in China fair in November, and expanded their offline community with a curated night at emerging underground Beijing club ZhaoDai in December. They’ve just put out an open call for submissions for their second issue, APPEARANCE, which they say will move beyond the strict focus on gay male culture to tell stories from other parts of the global LGBTQ+ sphere.

Missionary recently took part in LGBTQ-focused event series East Palace West Palace at Beijing’s ZhaoDai club (photos: -釒土- Weibo)

Ahead of issue two hitting the stands (Missionary is available on Taobao and select independent bookstores in Beijing, Suzhou, Chongqing, Taipei and London), I chatted with Zhu and Yu about their mission, the inspiration behind Missionary‘s first issue, rising icons on the Chinese LGBTQ+ scene, pervasive stereotypes around the culture, and recent, heated public discussion about China’s so-called “masculinity crisis.”

RADII: What are your backgrounds? How did you first get the idea for the magazine?

Missionary: We’re Zhu Zhaokang (D) and Yu Shiyuan (B). We were both born in the ’90s, with the same college major of art and design. We’re based in Beijing.

D has six years of experience working in the fashion magazine industry; B transferred from working in the luxury goods industry to working at a bookstore. We met in 2015, and wanted to start a studio together to do creative and visual design work, so we founded DaddyGreenBASEMENT. Missionary is one of our more important publication projects since founding the studio.

Missionary founders Zhu Zhaokang (aka Dimethicone) and Yu Shiyuan (aka Blackmustard)

Tell me more about DaddyGreenBASEMENT.

DaddyGreenBASEMENT is our passion project for now. We both have full-time jobs, but in our free time we join the art and culture social scenes that we like in the form of a studio. We’ll definitely make it our brand down the road, as we have imagined many possibilities for it — it’ll cover publication, new media, exhibition and art installation. All of this can happen under the DaddyGreenBASEMENT name, and we’d love to have an actual venue to develop these ideas, like a shop or a bar. I could talk for a long time about how the name came along, but long story short, “daddy” and “green” represent the two energies that we think are worth pursuing — “bravery” and “hope.”

The magazine is called Missionary, and your mission statement ends with a Bible quote: “And then you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” You also dressed up as Mormons at the Shanghai aBC book fair. Are you religious? What part of the Bible resonates the most with you in connection to the creation of the magazine?

We were both baptized into the Christian faith early on. D is Catholic, B is Protestant. The Mormon look we did at the aBC book fair was inspired by Google results of gay pornographic sites when we searched “Mormon”. It seems that religion can always be associated with homosexuality and prohibition. Repression can always result in rebellion. Apart from “And then you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free” (John 8:32) as a criterion for Missionary, we also have “I have the right to do anything — but I will not be mastered by anything” (Corinthians 6:12) to light our way.

Repression can always result in rebellion.

Elsewhere in the magazine’s mission statement you write: “To restore the truth of a community through sexual activities” and ”To present the life status of the gay community in an artistic form.” Is there a higher purpose or deeper meaning beyond that?

I don’t think it qualifies as a higher purpose, and meaning is only given through time and readers’ feedback. Our purpose is really simple: to share stories of gender minorities and to decrease prejudice via reading. Though it’s hard and even unlikely to achieve, we do it anyway.

Our purpose is really simple: to share stories of gender minorities and to decrease prejudice via reading.

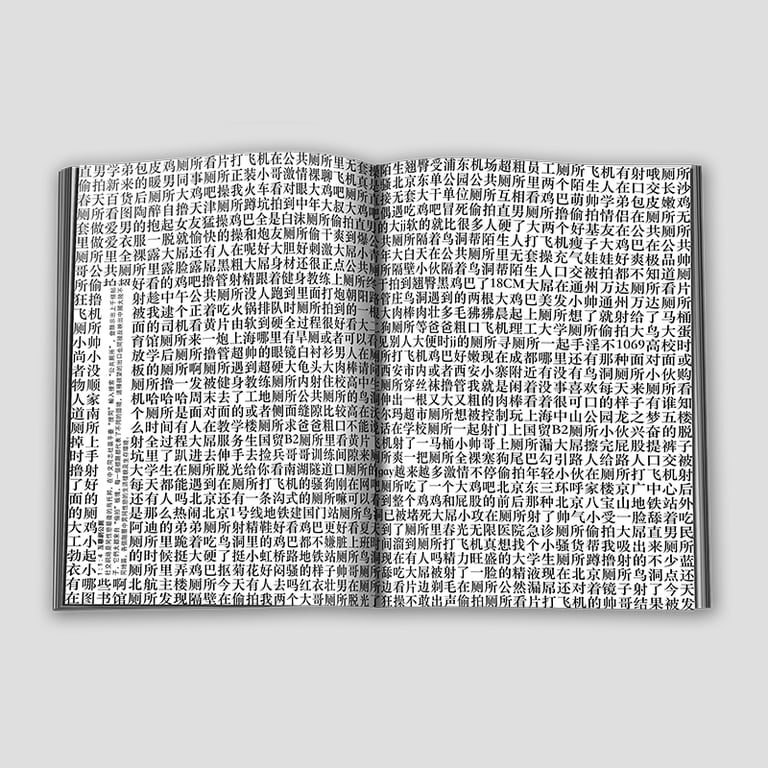

The first issue is called Public, thoroughly presenting male gay sexuality in public spaces through sections entitled “where”, “what” and “who.” You quote Laud Humphreys in your opening text, and in the first section, “where,” you break down a few points from his book Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places. I think referencing this historical, academic and progressive piece sets the tone of the magazine. How did Humphreys’ thinking inspire the first issue?

It’d be more accurate to say that we were inspired by social phenomena like male gay sexual activities through “glory holes”. Being a member of this group, we’ve all had sexual experiences in public, some more than others. Much like Dr. Laud Humphreys, to conduct academic studies, his own behaviors and the way he gained trust from interviewees may not be as honest as he claimed.

Male sexual activities in public bathrooms have been around for a long time, be it in China or abroad, as bathrooms are the most basic sexual interaction venue for gays. Even in the internet age we’re in now, “glory holes” exist in every city. Our first issue’s topic was originally public bathrooms, but we realized one single venue doesn’t fully depict the gay community that feels constricted in public spaces.

The issue also features lots of striking photography. As a visual arts-oriented organization, what is your creative process here? Do you lock in a theme and then arrange specific photoshoots afterwards, or do you collect photographs first then make your selections and appoint the theme? How do the text and visuals feed back on or influence each other? What is your guiding philosophy in syncing text with visuals?

The issue also features lots of striking photography. As a visual arts-oriented organization, what is your creative process here? Do you lock in a theme and then arrange specific photoshoots afterwards, or do you collect photographs first then make your selections and appoint the theme? How do the text and visuals feed back on or influence each other? What is your guiding philosophy in syncing text with visuals?

First, we lock in the theme, then we create a tight structure and work our way down, which is the work process of traditional print media. Thanks to D’s experience working at fashion magazines, we’re able to keep a nicely organized workflow. So we first make plans according to our themes, then we complete the production part.

We do it all, from booking the photographers or doing the photography ourselves, to locking in locations and talents, to post-production. Text carries the task of describing the visuals, but these days people are more accustomed to images than text when it comes to reading habits, so we try to minimize text and let the photos talk, leaving interpretation open to the readers.

In addition to writers and subjects from China, you also feature people based in Denmark, Canada, Russia and Australia. Why is it important to have such a global perspective when the main language and main readership of the magazine are Chinese?

In addition to writers and subjects from China, you also feature people based in Denmark, Canada, Russia and Australia. Why is it important to have such a global perspective when the main language and main readership of the magazine are Chinese?

The main characters of the magazine are fellow Chinese gay people, and what we want to do is make a magazine that’s focused on Chinese gender minority communities, but we can’t help noticing the equality movement and queer arts outside China. Due to our national conditions, and for political reasons, we don’t have many professional organizations or platforms to host our voices, so we must look back on how gay communities around the world have developed and try to find inspiration and even direction from some of their protagonists. In fact, after the completion of our first issue, we realized that male gay communities share similarities no matter what system they’re part of.

After the completion of our first issue, we realized that male gay communities share similarities no matter what system they’re part of.

The Chinese government currently maintains a “Three No’s” policy with regard to homosexuality: No support, No opposition, No encouragement. What kind of support systems or difficulties did you encounter during the creation of the first issue?

In this day and age, most of our insights come from different networks of people. We’re acknowledged by some arts and culture organizations, and we join diverse activities in our day to day lives. We’re also encouraged by friends who work to promote queer culture, and we cross paths in real life.

As for difficulties, the main thing is that we kept getting rejected by printing factories because of the content of our magazine. It shows that the domestic market is still monopolized by mainstream values, and we do not have the constitutional rights of free speech and free publication. In the end, we had to print our magazines in a small factory that wasn’t fully equipped. The paper, the binding and the printing craftsmanship — none of them met our expectation, which is a regret of ours. On the other hand, after the first issue was published, we were happy to see more and more people walking with us.

Talent show Produce 101’s Wang Ju created a stir during her run on the show last year. Some say that her physical appearance, which doesn’t conform to mainstream female beauty standards in China, led to her being adopted as an LGBTQ+ icon, and her quick rise to fame reflected the LGBTQ+ community’s capability to create a star. What do you think about that?

Talent show Produce 101’s Wang Ju created a stir during her run on the show last year. Some say that her physical appearance, which doesn’t conform to mainstream female beauty standards in China, led to her being adopted as an LGBTQ+ icon, and her quick rise to fame reflected the LGBTQ+ community’s capability to create a star. What do you think about that?

We watched some interviews with Wang Ju after the show finished. She talked about how she was just showing her true self on the talent show, the part of her that doesn’t care about others’ opinions. Personal charisma, plus being on a trending show, brought her to the attention of — and won her the affection of — the LGBTQ+ community. We think it’s partially influenced by Western culture: the strong female character is nicely represented by her, and this is a positive influence. Breaking some norms may help in pushing equality and stopping discrimination.

Related:

“China’s Beyoncé” Wang Ju Fails to Make “Produce 101” CutArticle Jun 25, 2018

“China’s Beyoncé” Wang Ju Fails to Make “Produce 101” CutArticle Jun 25, 2018

Post-’90s gay talk show host Gang Sida (姜思达) is one of China’s youngest thought leaders. Another content creator born after 1990, Mudan (戏精牡丹), is famous for his hilarious performances of female characters. They’re both great content creators with millions of online followers. Do you think they qualify as LGBTQ+ icons? Obviously, their reach goes beyond the LGBTQ+ community, but what do you think of these two young creators with open LGBTQ+ identities gaining fame and popularity?

The emergence of such artists shows that the country is slowly changing. Surely, good works and forms of expressions won’t go buried. They deserve to be called icebreakers, bearing risks and hopes. When people’s mentalities and aesthetics begin to change, and they become more open and diverse, they will naturally be attracted to quality work and forms of expression. As people get closer and receive influence [from these people], they focus and they think, and they rediscover themselves through [these works], changing their self-perception.

Related:

One supposedly positive stereotype about gay men is that they have elite, cosmopolitan tastes in areas like art, culture, and fashion. This stereotype of cultural elitism also suggests, in words used in Missionary, how some people are “trying to meet the standard” to fit in with “that part of mainstream culture that’s temporarily accepted.” What do you think about this stereotype?

This is something you can’t blame people for. The gay community needs such elite imaging to package themselves, or in other words, as a shield to protect themselves. Mainstream aesthetics have a massive population base. When outnumbered, a minority group naturally must improve its “quality”. Humans are natural imitators — following trends or general convergence [to a norm] is also a social phenomenon. The underlying gay community gets counted as elite, and elite means being accepted by mainstream aesthetic standards. Surely there are things about gay culture that aren’t known to people, aspects that are hidden in dark corners, which is what our first issue talks about.

The role of the “gay bestie” is seen more and more in pop culture in China, in the fields of literature, TV and film. I remember the first time I came across this concept in high school from watching My Best Friend’s Wedding. In the movie, Julia Roberts’ best friend is a charming gay lawyer who always has her back. This movie came out in the US in 1997. Now, in China in 2019, what do you think of the “gay bestie” role in our pop culture?

The role of the “gay bestie” is seen more and more in pop culture in China, in the fields of literature, TV and film. I remember the first time I came across this concept in high school from watching My Best Friend’s Wedding. In the movie, Julia Roberts’ best friend is a charming gay lawyer who always has her back. This movie came out in the US in 1997. Now, in China in 2019, what do you think of the “gay bestie” role in our pop culture?

This is probably about how one looks at emotions. If you get easily influenced by a show and rush to imitate the behaviors you see in it, we think you’re lost. Of course, what happens in a show does happen in real life, but we all need to manage our own emotions and find suitable listeners. It’s much more meaningful to turn listeners into close friends, but it’s not easy. It can be random.

In the past year, there has been an ongoing discussion over a supposed “crisis in masculinity” in China, due to the use of androgynous imagery by certain pop culture figures. Over the past couple of months in particular, this discussion has been sparked by a photo contrasting Chinese boy band TFBoys and French footballer Kylian Mbappé with the caption, “Strong youth, strong nation; Sissy youth, sissy nation”:

“少年强则国强,少年娘则国娘”

In September 2018, both Xinhua and People’s Daily published “think-pieces” on “male characteristics,” with Xinhua using this phrase in the headline. From what I’ve observed, it’s as if half the crowd rallies for the kind of traditional masculinity embodied by action films like Wolf Warrior 2, while the other half follows programs like Idol Producer. What are your thoughts on the heated discussion and these polarized standards?

It’s actually a good thing that there’s a public discussion on wording like “sissy”(娘 niáng), and such pointed topics. On the other hand, it’s really narrow-minded to over-simplify the definition of masculinity, and even take it to a national level by switching concepts. This could also be a manifestation of being culturally insecure. I remember this quote from the TV series Pose: “Everybody needs somebody to make themselves feel superior. That line ends with us though. This shit runs downhill, past the women, the blacks, Latinos, gays, until it reaches the bottom and lands on our kind.” There will always be people who dominate the conversation with the loudest voice, so will there be disagreement.

You might also like:

Has China’s Food Delivery Boom Led to the Fetishization of its Drivers?Is a recent trend in China’s LGBTQ circles for “ordering” handsome delivery boys an imaginative spin on the classic “uniform fetish” or something more troubling?Article Oct 18, 2018

Has China’s Food Delivery Boom Led to the Fetishization of its Drivers?Is a recent trend in China’s LGBTQ circles for “ordering” handsome delivery boys an imaginative spin on the classic “uniform fetish” or something more troubling?Article Oct 18, 2018

How does your magazine come into play to counter some of the stereotypes surrounding gay men in China?

To be completely honest, we don’t put any hope in eliminating people’s stereotypes. As we mentioned earlier, we’re doing a tough and thankless job. It’s hard to even get recognition from our own community — this is our deepest realization after publishing the first issue. Another interesting fact is that there are more females than males interested in Missionary. It seems that female minds are more inclusive than males’, whether they’re straight or gay.

What’s next for Missionary and DaddyGreenBASEMENT? Missionary is defined as an LGBTQ+ magazine, and the first issue puts an exclusive focus on gay male sexuality. Will future issues switch this focus?

We’ve locked in the theme and direction for the second issue: APPEARANCE. The first issue is focused on the male homosexual community, as we’re part of that. The second issue will be a bigger topic. More easily-neglected characters will be included, such as women, elder homosexuals, the disabled, the physically and mentally ill, transgender people, etc. We’ll be looking at the entire LGBTQ+ community in the second issue, aiming to reflect the external imaging and internal state of mind of China’s gender minority groups via a series of artworks.

DaddyGreenBASEMENT will also throw a number of online and offline events. We’ll be co-releasing a gender-neutral accessory with an independent designer very soon.

How do people get involved in the making of future issues, online and offline?

How do people get involved in the making of future issues, online and offline?

We’ll be collecting stories from the public for our second issue. [Ed. note: find their open call for submissions here.] We look forward to establishing connections with gender minority groups and sharing each and all the compelling stories. You can follow us on WeChat (DaddyGreenBASEMENT) and on Instagram (missionary_magazine).

—

Gay identity is an “emergent masculinity” in China — to promote its very culture is to fight against the toxic masculinity that is still ubiquitous in Chinese society. Not only the gay community, but all marginalized groups can benefit from it. That also includes me, a heterosexual Chinese woman who is (according to my family and society at large) at the end of “the golden window to bear children,” as a common Chinese phrase — 最佳生育年龄 zuìjiā shēngyù niánlíng — has it.

To borrow the words of my favorite queen, Sasha Velour: “Let’s change shit up. Let’s get inspired by all this beauty, and change the motherfucking world.”

Buy your copy of Missionary magazine at their Taobao store, or at bookstores in Beijing (梦办 DreamCo), Chongqing (肩硬 JAMin), Suzhou (Forestbooks), and Taipei (朋丁 pon ding), Hong Kong (流動閱酷 Queer Reads Library), and London (Gay’s the Word). If you’re interested in contributing to the magazine, find the open call for their second issue here.