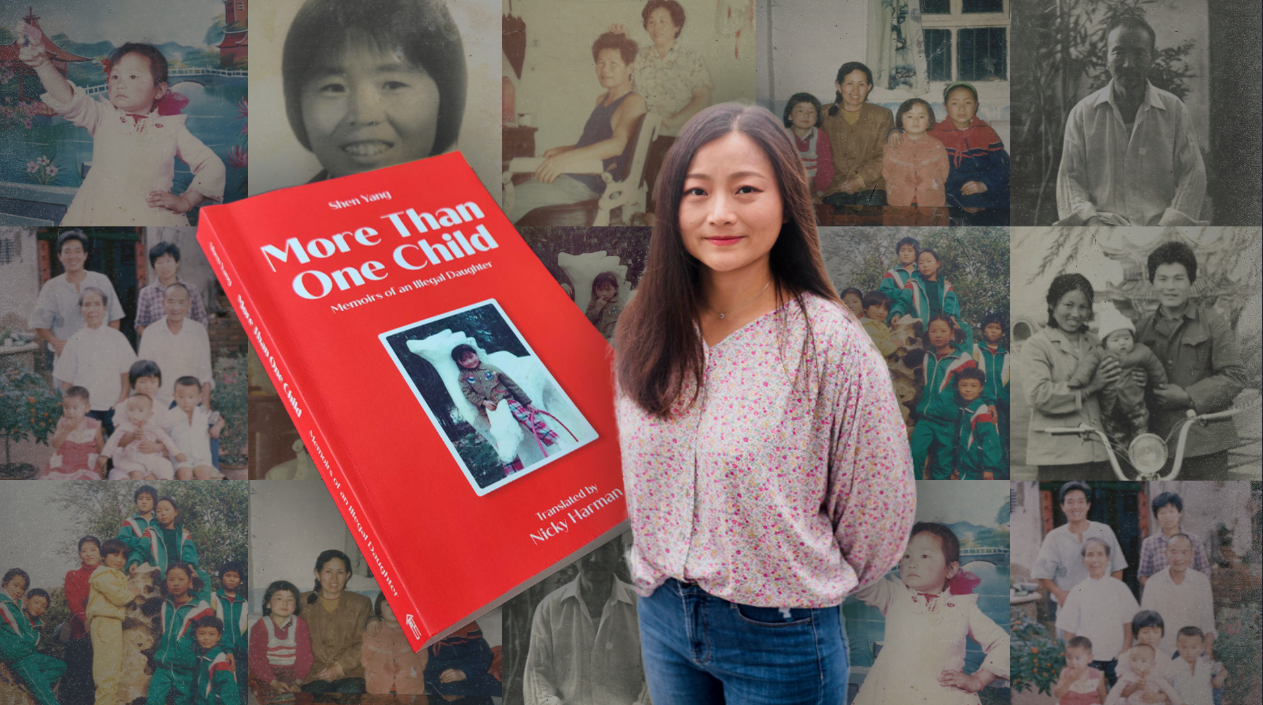

Welcome to 2021, when it is officially legal to have up to three kids in China. But it wasn’t long ago when the reality of having more than one child came with legal repercussions. In the autobiography More Than One Child, author Shen Yang documents, through courage and resilience, what it was like to grow up as an ‘excess-birth child,’ or heihaizi, during an era of stringent public policies. This facet of her identity would define every memory in life — both joyous and turbulent.

If Chen Danyan’s Only-Child Manifesto captured the reality of life as an only child, More Than One Child is an ode to kids from the other side of the coin — the ones who had to navigate the rugged terrain of illegality, secrecy, and shame upon birth. But despite that, Yang is more than the sum of her struggles. And above all, the book is a story about the greater community of excess-birth children.

Below, we are pleased to share an excerpt from More Than One Child, where the author lays bare recollections from her childhood. Beyond this scene-setting, we recommend picking up a copy of the book to better understand how the one-child policy shaped many lives.

You can purchase More Than One Child via Book Depository, Belestier Press, or Amazon.

On 1st January 1986, on a bright sunny morning, I finally saw the light of day. My mother, with me in her belly, had been on the run from the authorities for nine months. Because I was a New Year baby, they gave me a warm name, Yangyang, or Sun.

However, I was hardly a little ray of sunshine to my family. I had a sister who was four years older than me, I didn’t have a little willy, I broke a law simply by being born, and if the family planning authorities discovered my existence, my mother would be carted off to the clinic to have her tubes tied, and our family would be heavily fined.

So there I was, swaddled in a thick quilt. I may have chosen a lucky day to be born on, but I could not change my destiny.

Come what may, my mother had to give birth to a son in order to carry on the family line. The family could not afford the excess-birth fine and did not want my mother to be sterilized, so as soon as I was born, I was sent to my mother’s parents, Nana and Grandad. They lived in Sunzha Village, Yanzhou County, in Shandong.

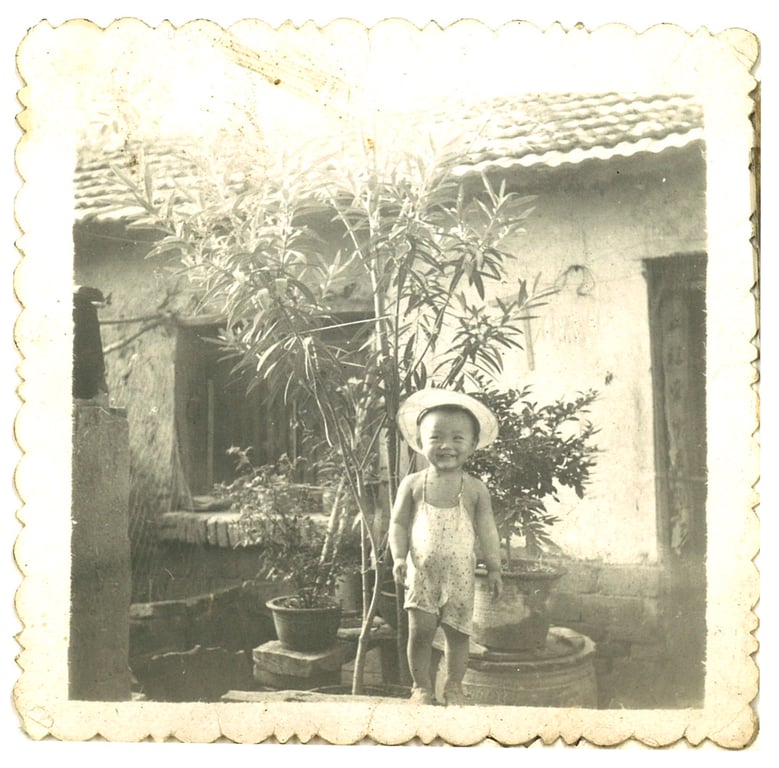

Nana and Grandad had lived in Sunzha for most of their lives. The area was relatively undeveloped compared to the nearest city, Jining; the air was clean and there was plenty of space to play outside. Grandad liked to get up early in the morning and stroll around the village, one hand behind his back, the other playing with two large walnuts, turning them in his palm. When he met someone he knew, he always stopped for a chat. Then he would walk to a little store at the entrance to the village to buy some baijiu liquor from a big vat, and take it home to enjoy.

Shen Yang at two years old with her grandmother in Sunzha Village

My grandfather’s biggest pleasure in life was to have a few cups of baijiu, a few peanuts, and some snacks every morning. It didn’t matter whether the snacks included meat or not as long as there was the drink. Without it, the day was incomplete. In his words, baijiu was the best thing on earth, it made everything, even a few scraps of pickled vegetables, taste wonderful. Nana called him an old wino, but he saw himself as kin to the wine-quaffing poets of ancient times. He used to listen to Chinese opera as he sipped, and when he had finished, he would lie back on his bamboo recliner, gently turning the two large walnuts in one hand. He had had them so long that they were worn smooth. From the small radio on the table came the guttural sounds of Beijing dialect. Warm sunshine filtered through the half-open door, making dust particles dance merrily in the air. Grandad lay with his eyes half-closed, rocked, hummed, and turned his walnuts.

Nana was the polar opposite to Grandad. She was always busy with something, usually at work on her flowers, herbs and vegetables in their yard. It was more of a vegetable garden than a yard, with every inch of earth planted. A big elm tree stood in the northwest corner, and there was a small plot with greens nearby. There was a large patch of peanuts on the east side, while the south wall sheltered pots and planters. In winter time, these were piled against the wall, the withered stems and flowers in them rustling in the chill wind as they waited to be revived by the coming springtime.

One cold day before there was any sign of spring, my mother and father arrived with their new-born, me, then left. I was a burden to them, but I became Nana and Grandad’s little treasure. At a little over one year old, I learned to walk by hanging onto the furniture as I followed my grandfather around the house. At two, I could walk well enough to stagger after him, pulling my toy duck along with me, as he walked to the shop. Sometimes, I messed around in the garden with my Nana; when she picked beans, I threw them to the hens; when she dug up her peanuts, I stamped around in the earth; when she put fertilizer on the flowers, I ran around the yard pulling the basket of cow dung.

The seasons passed, and soon four years had gone by. My parents visited me from time to time, bringing treats and toys, but I loved Nana and Grandad best. They took care of me every day, they loved and spoiled me, and no matter how naughty I was, they never laid a finger on me. I liked to snuggle up to Nana and listen to her stories. I used to pull her eyelids open when she was asleep. I liked going to the market with her. She swayed along in front, with a big bamboo basket over her arm. I trotted behind with a little ragbag over my shoulder. We strolled around all morning, and Nana’s basket was always full of all kinds of snacks. I spent the whole time stuffing my belly until it bulged like my little bag.

Happy times at Nana and Grandad’s home

I liked to go with Grandad to get water. He went in front with the carrying pole over his shoulder, a bucket swinging from each end, and I skipped along behind, pulling and dragging on the back one. As I waited for him to draw the water, I sat and played with pebbles. When he was ready and had the heavy buckets loaded at each end of the pole, he set off home, walking on the balls of his feet, with me at his heels. As Grandad puffed and panted, I thoroughly enjoyed myself splashing in the little puddles of spilled water.

Once, we met an enormous speckled cockerel that had slipped out of someone’s yard. He strutted around under a big locust tree, the picture of Mr High-and-Mighty. Grandad drew his water, I sat and played with pebbles, just as we usually did. Suddenly, the cockerel erected its large red comb, craned its thick neck, glared at me and charged. Quick as a flash, just as it was about to give my bottom a vicious peck, Grandad grabbed the carrying pole and lunged at it. The cockerel turned tail and fled. My terrified tears turned to laughter. At that moment, Grandad was my guardian angel.

In the big room of our house, in the northwest corner, there was a carved chest full of patterned ceramic jars of different sizes. They held Grandad’s favourite spicy salted peanuts, some fruits and pastries that Nana loved, and the cakes and biscuits that I could never get enough of.

Although Mum and Dad were not around, they gave Nana living expenses every month. Nana, of course, spent all this money on me. In the countryside in the early 1990s, not many children got to eat thin-skinned dumplings crammed with stuffing the way I did. My Nana was a clever cook. She not only produced all sorts of stuffed dumplings, but every once in a while she made me cakes with big red jujube dates in them.

Jujube cakes are always eaten at Chinese New Year in southwestern Shandong. The dough is rolled out flat, and then pulled into long strips; the cake is formed by coiling the strips around a date in the middle. These are arranged in circles and layered up into a tower. The shapes vary from family to family, everyone does it differently. They’re delicious and have a special meaning too, symbolizing people’s hopes for prosperity and a better life in the coming year.

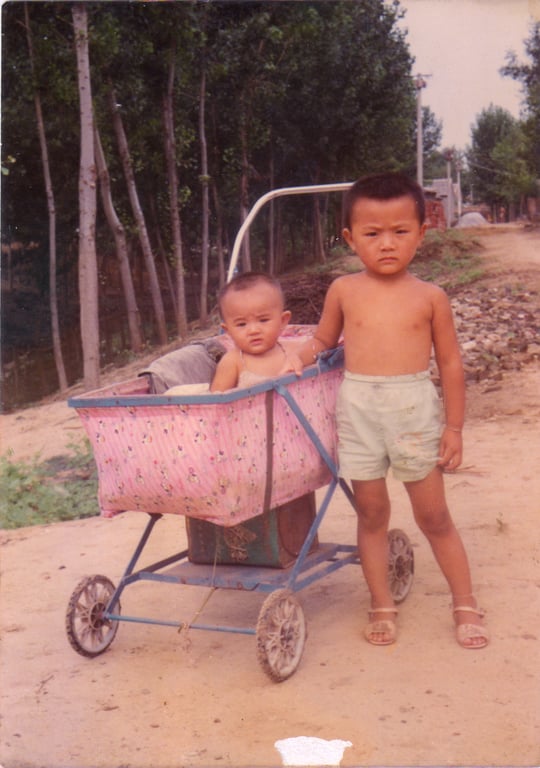

Shen Yang with her younger sister, Star

Nana’s jujube cakes came in different flavours and shapes. With her nimble fingers, she used to push a few jujubes into the dough and just like that, she’d made a small animal. When the cakes had been steamed and taken out of the steamer basket, she deftly rubbed a little bit of the jujube paste between finger and thumb to form very small round bobbles which she stuck on top of each one, where they sat looking at you, like funny little eyes.

I would rush out of the door, clutching the little animals that Nana had made so carefully, and show them off to the other urchins. I was only four and a bit, I didn’t know any better. Yan, who was three years older than me, once managed to get a cake off me. I didn’t care, I gnawed at the stale mantou bun she’d given me in exchange, grinning and giggling.

Jujube cakes were a big treat, and the kids who didn’t get any were jealous. There was one six-year-old who was tormented by the sight of Yan gobbling down the tempting morsel, and the little swine sneaked into our yard when he knew I wasn’t there and told Nana about Yan persuading me to give up my cake. Nana was furious and I suffered the consequences too.

From that day on, Nana announced, she would not be making New Year jujube cakes again. ‘You can go and ask the moon and the stars,’ she told me. I begged and begged, and Grandad begged on my behalf, but he got short shrift. ‘Don’t you play Mr Nice Guy,’ she told him.

Grandad couldn’t say anything to that, so he just puffed and snorted through his whiskers.

And that was the end of the fragrant smell of steaming jujube cakes in our yard, for a good long while.

Shen Yang with her siblings, cousins and grandparents

One day, guests arrived to see an uncle and aunt whose house was at the back of ours. My aunt produced a table full of delicious food and steamed a pot of jujube cakes. I was playing with the chicks in the yard, but the moment I smelled them steaming, I started walking, drawn by the smell.

I didn’t ask for one, or help myself, I just stood staring at the freshly cooked jujube cakes with big, round eyes. Jujube cakes are not my favorite, but I had not had any for a long time and the fragrance made my tummy rumble.

My aunt looked at me and smiled. She took out a cake from the steamer basket, put it on a small saucer and gave it to me cheerfully. My eyes shone as I took it and ran away.

When the family were sitting in the back yard preparing dinner, I brought the saucer back, now empty. I stood there biting my lip, ogling the jujube cakes on the table. My aunt gave me another one without saying a word. But ten minutes later, I was standing in her yard with the saucer empty again.

‘This girl must be starving!’ my aunt said. ‘She’s had two jujube cakes, and it looks like she’s going to scoff the lot!’ And she ran to the front yard and called my Nana, ‘How many days has Yangyang gone without food?’

Nana rushed out of the house where she was cooking flatbreads, ‘What’s going on?’ she demanded.

‘I just gave Yangyang two big jujube cakes, but twenty minutes later, she’s eaten all of them! And now she’s back with an empty saucer again. She can have as many as she wants, it’s not that, but I don’t want her to overeat,’ said my aunt anxiously. ‘Her uncle can only manage two at most before he’s full.’

Nana said nothing. She went straight to the coop at the foot of the north wall. On the ground, the chickens were fighting over the pieces of cake I had thrown to them. My aunt came in and looked astonished.

The thing was, her jujube cakes were doughy and didn’t have many jujubes. I had been spoiled by Nana. I had picked out all the jujubes and eaten them, and given all the rest of the cake to the chickens.

Nana was extremely apologetic. ‘I’m so sorry,’ she said. ‘Don’t ever give her anything again, she’s a spoiled brat!’

My aunt stood looking at the cake bits, as if she did not know whether to laugh or cry.

In spite of my misdeeds, my adored grandmother never laid a finger on me.

And after that, she used to cook up a few jujubes on their own if I was peckish.

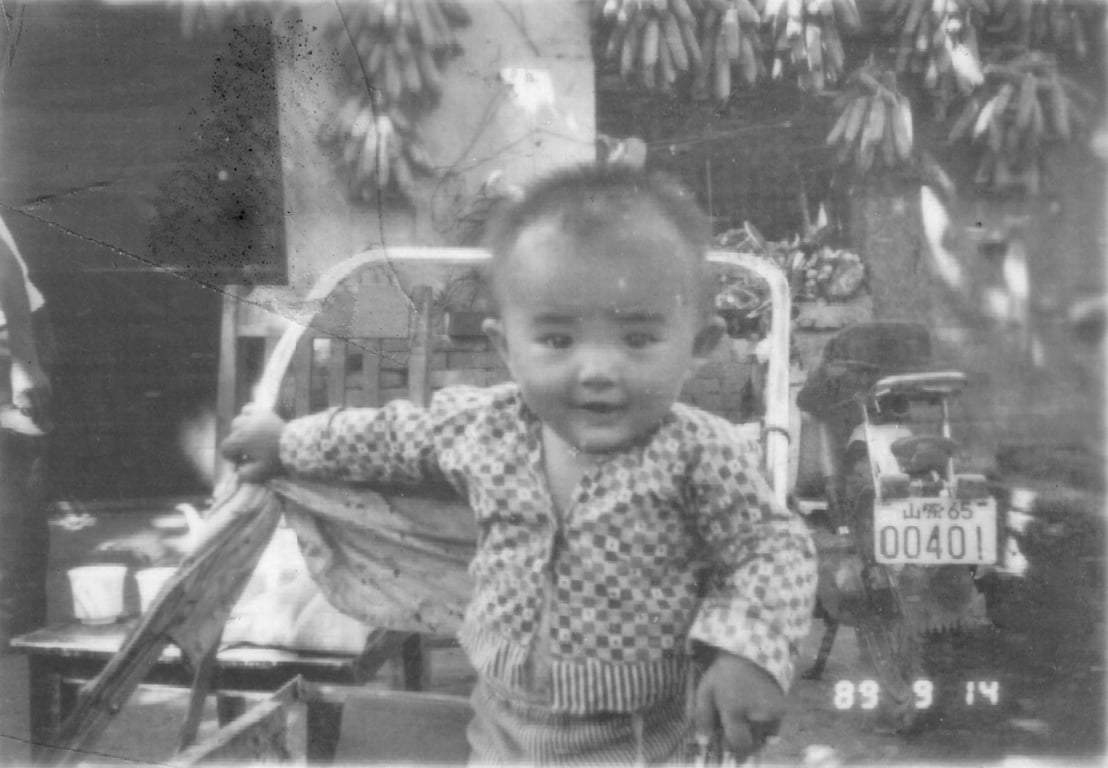

Shen Yang’s youngest sister, Star

While I was being kept out of sight and having the time of my life at my grandparents’ house, my two younger sisters came into the world. As soon as they were born, Third Sister was spirited away to Granny and Grandpa’s house, and Fourth Sister joined me at Nana and Grandad’s. The day she arrived, there was a buzz of activity in the little yard. There was my father, busy unloading the car and carrying bags into the house. There was my mother, washing baby bottles and making up formula milk. Nana was happily moving furniture around and making up a cot bed. Grandad was walking around the house, this new little baby in his arms, crooning to her.

I sat outside in the yard, bawling my eyes out.

‘What’s up? What’s up?’ Grandad was the first to come out to me, still holding the baby.

‘No! No!’ I went into full tantrum mode, rolling around on the ground and screaming.

‘Ai-ya! Don’t lie in the dirt, get up!’ Nana heard me and came out too.

There was a roar from my father, ‘Whatever’s the matter? Get up, you little brat!’

That only made me cry harder, and the tears poured down my face.

‘Now, now, Yangyang, what’s upset you so much?’ This was my mother.

She squatted beside me on the ground and put her arms around me. I snuggled up to her, still casting glances at Grandad and the thing he was holding. Grandad twigged immediately and brought the baby over, ‘Meet your little sister.’

‘Little sister?’ I frowned at her puckered purplish face. I thought I’d never seen anything so hideous. ‘I don’t want an ugly-mug sister!’

They all roared with laughter, Nana and Grandad, Dad and Mum.

When everything had settled down, my parents slipped away. It was towards the end of 1989, the calm before the storm.

All images via Shen Yang