It mushroomed in 2019 — we don’t mean the Covid-19 pandemic, either. Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you must have noticed: The previously overlooked world of fungi suddenly permeated mainstream culture, appearing in everything from director Louie Schwartzberg’s 2019 documentary Fantastic Fungi (find it on Netflix) to Malaysian-Norwegian author Long Litt Woon’s critically-acclaimed 2019 memoir The Way Through The Woods: On Mushrooms and Mourning.

Phyllis Ma herself caught the fever in 2019. The Chinese American photographer, who was born in Guangzhou, South China before moving to the U.S., has a knack for making seemingly ordinary things special, hence her Instagram moniker @specialnothing.

The sum of her passions, the 35-year-old who studied printmaking at The Glasgow School of Art and fashion design at the Fashion Institute of Technology began zooming in her lens on fungi after paying a visit to an organic mushroom farm in Brooklyn, New York City, and is now known for her eye-popping prints of fungi, which are the subjects of a series of zines titled Mushrooms & Friends.

Recognizable by her shock of electric blue hair, the photographer turned fashion icon has recently taken a more niche interest in Chinese mycology.

“Although I ate a lot of mushrooms growing up — like straw mushrooms, wood ear, tremella, and caterpillar fungus — I had no idea that they were anything special,” Ma tells RADII. “Only in the past few years have I realized that China has such a rich mycological culture, history, and cultivation expertise compared to the rest of the world.”

The artist has been featured in or created work for NYC’s top publications like The New Yorker and The New York Times, France’s Le Monde and Libération, and Germany’s Page Magazine, but there is so ‘mushroom’ (pun intended) for more fungi-related stories. RADII is elated to be Ma’s first interview in Asia:

RADII: Have you been back to China since you moved from Guangzhou to the U.S.?

Phyllis Ma: I’ve been back a few times to visit family in Guangzhou, Anhui, and Chaozhou, but less so in recent years. My last trip was to Chengdu and Guangzhou in 2017. Unfortunately, I was not obsessed with mushrooms at the time, so I’ll have to make my next trip extra myco-focused.

I’m curious if mushrooms have entered popular culture and fashion in China. From what I see online and talking to friends there, it seems like something that the younger generation hasn’t gotten into it yet, but I guess it also depends on the region.

RADII: You hit the nail on the head. Mushroom mania hasn’t quite swept through Asia the way it has in the U.S., possibly because fungi have always been in the background of our consciousness. For example, medicinal mushrooms have long been used in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Thoughts on TCM? Pure fluff or true facts?

PM: I’m a big fan of TCM, and I’m fascinated by how it’s deeply ingrained in Chinese culture and food. In my personal experience, TCM isn’t a panacea, but can be really effective for certain conditions that are resistant to Western treatments. Finding an experienced practitioner is really important. Also, it requires a lot of patience and doing consistent treatments over a long period of time.

RADII: Have you noticed any Western misconceptions about Chinese mycology?

PM: Yes, there’s one that comes to mind. Some mushroom growers in the U.S. claim that all mushrooms from China are toxic. I’m not sure if they actually believe it, or if they espouse it as a way of self-promotion. Either way, the results boil down to a baseless and xenophobic belief that assumes that anything ‘Made in China’ is bad.

Of course, there are poor quality and even mislabeled mushrooms coming from China, but the fact is, China also has some of the most high-tech farms, and currently produces around 90% of mushrooms globally. To claim that all Chinese mushrooms are toxic is not only absurd, but also blatantly Sinophobic.

RADII: It’s heartening to see more youth taking an interest in nature, especially since being cooped indoors during the Covid-19 pandemic. Your hobby sees you clambering over woodpiles, trudging through thickets, and literally getting your hands dirty. Have you always had an outdoorsy streak or does your new passion simply call for it?

PM: Growing up, I’ve always lived in cities, so nature wasn’t easily accessible. In recent years — first through climbing and then mycology — I have been motivated to spend more time outdoors. My partner, Sam, who grew up in the Swiss Alps, is also a big inspiration. His father was a climber and a mountain guide, so he naturally grew up with a lot of knowledge about the outdoors. I learn so much from him when we go hiking and foraging together.

RADII: While you do take photos of your subjects on site, your expertise lies in highly-choreographed studio shots. How do you ‘chauffeur’ your models from one location to the next?

PM: That’s a good question, because I really do have to strategically transport the fungi until I can photograph them. If I’m lucky to be staying near nature, I can just carry the mushrooms by the stem or in a paper bag.

It’s more complicated when I’m in New York City. To protect the mushrooms on the trip home, I wrap them in wax paper and then place them in a tupperware, with some holes in the lid for airflow. I always carry a few different sizes of tupperware on forays (organized like Russian dolls), and a pill organizer for the extra tiny specimens.

RADII: I know it’s like asking a mom to choose favorites from her brood, but which mushroom tugs at your heartstrings the most?

PM: I definitely give a different response whenever I’m asked this because it’s so hard to just pick one. Bamboo fungus or stinkhorn is definitely one of my favorites. First of all, it’s hilariously phallic. I love that it can be both intriguing and repulsive at the same time. If you’ve ever smelled one, you will know what I mean. Also, it’s pretty ingenious that bamboo fungus utilizes smell as a way to attract insects that, in turn, help to spread its spores.

RADII: Have you ever experimented with magic mushrooms? *Koff* With photographing them, I mean.

PM: I will just say that I have been photographing some, so stay tuned for that.

RADII: Your passion for photographing fungi has opened your eyes to some pretty dope discoveries, like the Daoist devotion to mushrooms. Tell us more.

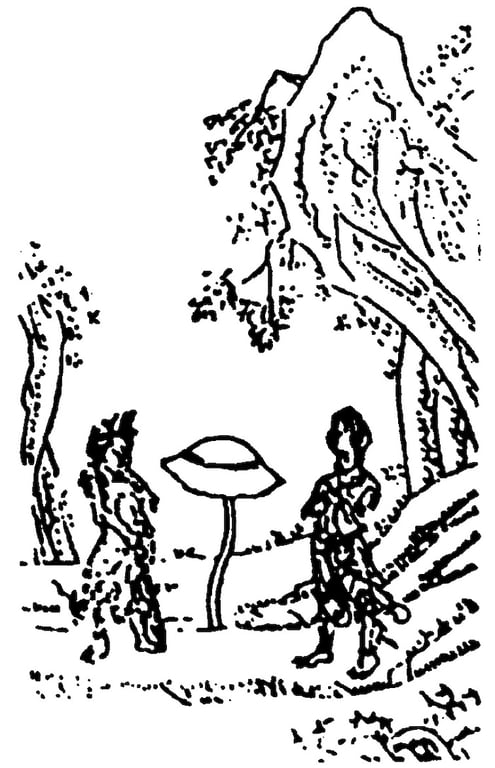

PM: I’ve been searching for mentions of mushrooms in Chinese history, and I came upon a Daoist text from the early 11th century called Numinous Treasure Catalogue of Mushroom Plants (Taishang Lingbaozhicao Pin 太上灵宝芝草品). There are 127 drawings of different types of divine mushrooms and herbs, and details on how to find them. The drawings are absolutely amazing and fantastical.

“Some divine mushrooms [in Daoist texts] can appear in the form of humans or even be protected by two guards.”

It’s not clear if the text correlates to actual mushrooms, but it’s possible that it might’ve been inspired by lingzhi or even Amanita muscaria and other hallucinogenic mushrooms.

RADII: You also recently experimented with potting your own lingzhi bonsai.

PM: So I fell into a rabbit hole researching lingzhi bonsai (灵芝盆栽) on Chinese websites like Bilibili and Weibo, and I stumbled upon a documentary showing two different ways of creating lingzhi bonsai. One method was grafting lingzhi together, and another was fusing together dried specimens. I’ve been growing Ganoderma lucidum at home for the past few months, so I got to try out both methods.

For my bonsai, I ended up harvesting two brackets, fusing them together, and adding the final creation to a potted plant. It feels like the mushroom and I collaborated on a sculpture together.

RADII: Fungi aside, your other photography projects point at an interest in comestibles. Is it safe to assume you are a — forgive the cliché term — ‘foodie’?

PM: That’s really funny because I’m not a foodie at all! It’s more that I like to explore food as a metaphor, which is how my mushroom project began. I was intrigued by mushrooms’ role as both food and an agent of recycling and sustainability.

RADII: What are some mushroom-related goals you hope to manifest in 2023?

PM: I would love to connect more with Chinese mycologists and mushroom growers. Please get in touch if you happen to be reading this!

I’m also really looking forward to visiting China whenever I can next. I’d like to visit Yunnan, the Tibetan Plateau, and as well as farms that cultivate lingzhi, morels, and bamboo fungus.

RADII: I have a good feeling about this given the recent relaxing of rules. See you in China, hopefully!

All images courtesy of Phyllis Ma unless otherwise stated