Rainbow Chan is an artist in the fullest sense of the word. Her practice stretches across visual and performance art, electronic music production, theoretical writing, sound art, DJing and onwards. Particularly noticeable in her work is the fruitful coalescence of electronic music and visual art, a dynamic bolstered by her inextricable inclusion of personal and theoretical understandings of China.

Sitting outside one of Beijing’s hutong bottle shops this past October, Chan told me about the importance of hybridity to how her work operates, her electronic music moniker Chunyin, her unique relationship with the Chicago dance music genre footwork, and how she has personally developed within the context of her artwork.

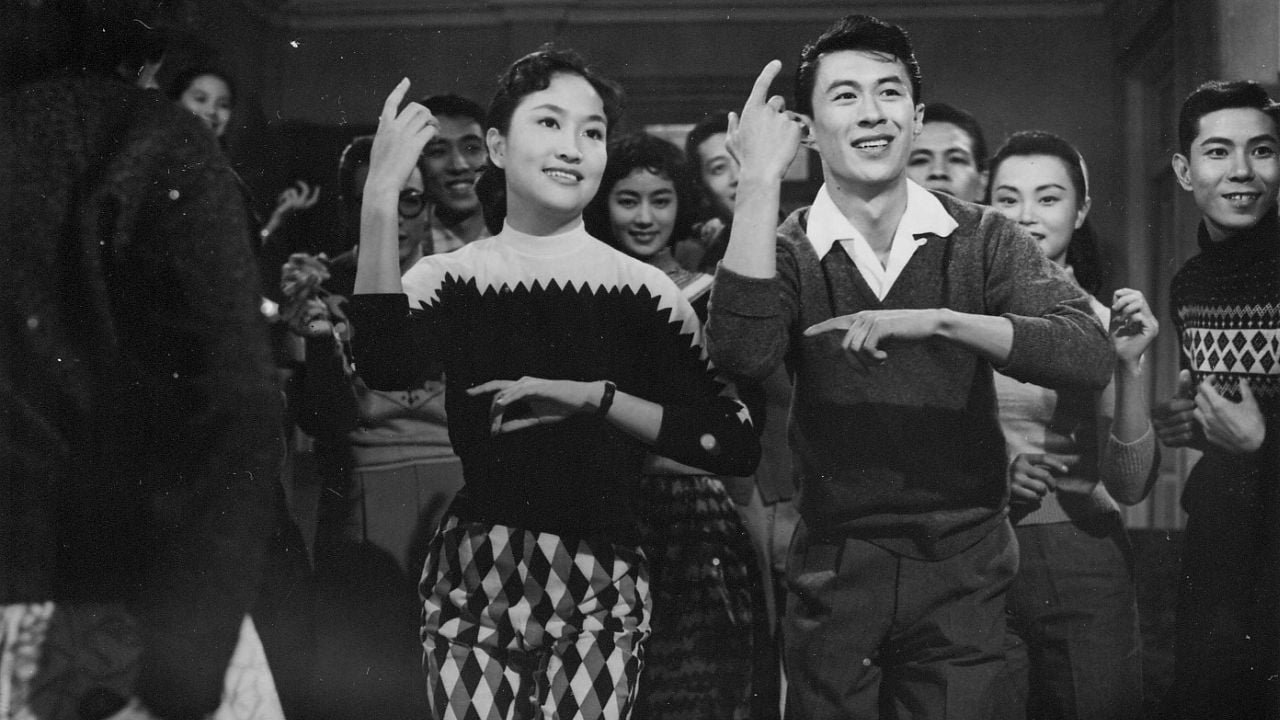

Rainbow Chan in Shanghai (photo by RADII Visual Editor Thana Gu)

This autumn, Chan spent a month in the outer reaches of Beijing’s sixth ring road for an artist’s residency at the 4A Beijing Studio Program. During our meeting there, we got speaking about the prevalence of counterfeit shops in the town where she was living, a subject of avid interest for Chan. Her currently in-the-works Master’s thesis is focused on shanzhai, a slippery and increasingly theoretical umbrella term for trademark-impinging and counterfeit goods, particularly those made in China.

A day earlier, Chan had presented Gloss, a performance art/electronic music hybrid work at prolific Beijing non-profit I: project space. The dominant motif was a pair of spectacularly fake shoes that she’d found in a Guizhou shopping center — although blatant rip-offs of couture brands are common, the inventive and cheeky appropriation on display in this pair immediately appealed to her. Gloss featured the artist’s own music, which Chan says emphasizes the shanzhai theme: “a lot of the songs were bootleg edits that I’d made, songs in which I’d sampled bits of text from real ads, or I had listened to a bunch of ads by Adidas or whoever, and tried to mimic the style and tap into that kind of language.”

Continuing on the topic of electronic music, Chan brings up Fatima Al-Qadiri’s 2014 album Asiatisch, an enigmatic, parodic depiction of a self-described “imagined China.” The album presents sonic stereotypes that represent China to those — like Qadari herself at the time of Asiatisch’s release — who have never been there. Chan’s feelings about the album align with a number of contemporary critics who ascribed a potential harmfulness to the album’s reductive concept and its reproduction of signifiers that are often co-opted as racist tropes. “I hadn’t really heard her stuff before, but when I did I had this really emotive response, where I felt quite confronted as a Chinese person listening to it and trying to unpack it,” Chan says, continuing:

Hearing a reiteration of clichés being made by someone who’s not Chinese, even if it is intended as reflexive and critical, caused a lot of tension in me. I really love her music, so it pushed me towards thinking about this idea of originality, copy, stereotype, and of images and sounds that help to perpetuate different ideas of people.

The concept of hybridity is essential to Chan’s art. Continuing to talk about shanzhai and the closely associated idea of hybridity, she says: “The more I read into it, the more there is to unpack. It’s not just some funny letters being scrambled up — the counterfeit market exists because China is the largest manufacturer in the world, and there’s so much inequality in global trade. The branding of luxury goods is such a bizarre thing anyway. If the same factories are making the same things, and only one has the authentication, how does that make [one] real and [the other] not real? All of these things have exploded in my research, which makes me want to look at all of these many different tangents coming out of shanzhai.”

The concept of shanzhai often operates across a particularly weighted dynamic: netizens unite to laugh at what are (often) Chinese-made products, at their obviousness fakeness or at the garbled, misspelled English of brand names or slogans. Often, onlookers’ reactions to shanzhai products reveal a thinly veiled racism, a dynamic that Chan calls a “new Orientalism.”

As someone who is part of the Chinese diaspora (Chan is based in Sydney), she says, “there are already so many stereotypes I had growing up of what a mainland Chinese person should be like, which obviously I don’t think are true now that I’ve experienced it. So, what I’m interested in is not giving a moral judgment, but looking at shanzhai as an intersection of all of these complex things. It doesn’t mean these things can’t be funny, but when you look at all of these elements you start to see it as a global issue: it’s important not to think of shanzhai as some accidental Chinese hipster thing, but as the product of a global issue.”

For an artist with such broad interests, it’s perhaps not surprising that even when homing in on particular projects, Chan’s output remains difficult to define. Take her electronic music moniker, Chunyin. Her most recent release was the well-received LP 偽承諾 Pseudo Promitto, which came out in April on fellow Australian producer Air Max ‘97’s label DECISIONS. Sonically, it shares affinities to the music of a group of disparate global producers who are making difficult to define, hybrid-sounding and very fresh electronic music (sometimes called “post-internet” or “deconstructed club music,” labels that no one seems to think are suitable.)

Related:

6 Young(ish) Producers and DJs in China Worth CheckingArticle Feb 28, 2018

6 Young(ish) Producers and DJs in China Worth CheckingArticle Feb 28, 2018

“I’m not a purist of any genre,” Chan says about her output as Chunyin. “I like having a bit of everything, trying a bit of everything. I think that if you become too strict with the boundaries of what you do or what you consume you can limit yourself, and for me personally I feel it can make it less elitist. Nonetheless, I think that thematically my practices all have this narrative, whether it’s about the hybrid, flexibility, or double consciousness.”

Appropriately for an artist who once described one of her songs, “Last,” as “a young Haruomi Hosono and Kylie Minogue on a hot Tinder date,” Chan’s musical influences are broad and hybrid. She mentions footwork — a style of sample-heavy dance music that originated in 1990s Chicago, characterized by a rapid, 160bpm tempo and a particular style of dance that evolved alongside it — as an influence, speaking of its idiosyncratic resonance with her memories of hearing “traditional Chinese drumming and lion dancing” during childhood.

“I grew up with a lot of that, and my uncle was in our village lion dancing troupe,” she says. “I remember one of the most distinct visceral experiences that I had with music was when I was about 3, and standing next to the lion dancing drum and hearing it vibrate in my body, it making my heart feet a bit funny, and thinking, ‘I really like this, it’s really exciting.’ In this drumming there’s so much variation in the meter and tempo, just like a DJ Rashad footwork track might have.”

Chan looks backward in recent musical history to note a similar dynamic between the Wu-Tang Clan and Chinese culture, and questions her own appropriation of the format of footwork. “I know as a Chinese person that is tangentially making, consuming and DJing footwork that maybe there’s some problems with that, if I’m not part of the community. But I think there are some hints and elements that just allow the sound to speak across, which I really like and appreciate.”

Chan is currently in the early stages of conceptualizing a project that encapsulates much of what makes her work unique. Photographs on her Instagram document this nascent project, showing her meeting with a group Weitou elders in Hong Kong. The Weitou were among the first people to settle in Hong Kong, during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), and are considered to be indigenous to the region. Although they were there hundreds of years before the British, the common colonial narrative is that beyond a few fishing villages, there was nothing in Hong Kong before the British arrived, and so the earlier Weitou history is systematically written out of history and subsumed into an imperial rags-to-riches story.

Chan recently immersed herself in the rich tradition of folk singing, especially by women, in these indigenous Weitou communities, something that inspired her to learn more about the Weitou language. “It’s not something young people now are encouraged to learn about, even for my parents’ generation it was the same. If other people heard that you had a rural accent, they would tease you and assume that you were from a lower class. So, for whole generations from the ‘60s to the ‘90s, no one really wanted to learn what came out of this culture. When you went to school it was always in Cantonese, so this Weitou language was — and is — basically disappearing, and I feel like the disintegration of the language is like a metaphor for the loss of culture.”

Chan’s plans for the project are typically ambitious: part performance art, part live music, part theater, part nightclub. And it’s a lifelong project: “To be able to come back to something that is so rooted in time, place and people and flesh and bones, and to do it through music and through community, gives me goosebumps… It’s so important and beautiful.”

As Chan continues along her creative trajectory, she admits that in the long term she wants to develop more behind-the-scenes work as well — organizing workshops and teaching classes, as well as facilitating and producing for other artists. And as with her burgeoning Weitou project, she wants to do more direct community work. “Making music can be so isolating, and it’s not great to become super narcissistic and believe that you’re the center of the universe,” she says. “To extract yourself from that and make stuff that is ‘pro-ductive,’ actually being a ‘pro-ducer’ in the literal sense of the word — that is something I would like to do.”

—

Cover photo: Rainbow Chan in Shanghai (photo by RADII Visual Editor Thana Gu)

You might also like:

Yin: SCINTII & Dirty K Remix Berlin Producer mobilegirlArticle May 25, 2018

Yin: SCINTII & Dirty K Remix Berlin Producer mobilegirlArticle May 25, 2018

Experimental Filmmaker Sam Miers Explores a Lesser Seen YunnanArticle Oct 16, 2018

Experimental Filmmaker Sam Miers Explores a Lesser Seen YunnanArticle Oct 16, 2018

Beijing Label S!LK Wants to Bring “Drastic” Sounds to the Club (and the Internet)Article Nov 20, 2018

Beijing Label S!LK Wants to Bring “Drastic” Sounds to the Club (and the Internet)Article Nov 20, 2018