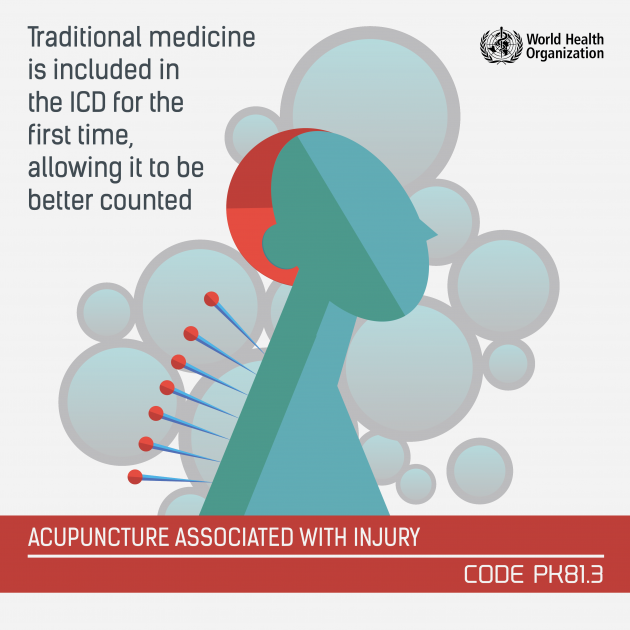

Next year, the World Health Organization (WHO) is set to officially adopt and recognize the 11th edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD), the “bedrock for health statistics” in the WHO’s own words. In this new edition, the ICD features data on Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practices for the first time. The move is an exciting one for acronym enthusiasts, but a polarizing one for those in the medical profession.

To some, this is the long overdue international recognition of healing practices with a millennia-long history; to others, it is a dangerous endorsement of a hocus pocus, fraudulent mode of thinking.

Steven Salzberg, a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering, Computer Science, and Biostatistics at Johns Hopkins University, seems firmly in the latter camp. Writing in Forbes last month, he variously labelled TCM as a “scam” and a “belief system” on the level of “magic”. Salzberg argues that “by endorsing TCM, the WHO is taking a big step backwards.”

There’s no legitimate reason to use terms such as “Chinese” medicine, or American, Italian, Spanish, Indian, or [insert your favorite nationality] medicine. There’s just medicine–if a treatment works, then it’s medicine. If something doesn’t work, then it’s not medicine and we shouldn’t sell it to people with false claims. The same is true for alternative, holistic, integrative, and functional medicine: these are all just marketing terms, with no scientific meaning. They merely serve to disguise sloppy, unscientific thinking at best, and in a less charitable interpretation, outright fraud.

As the Nature article points out, TCM has been a scam for decades: it was revived and heavily promoted in China by former dictator Mao Zedong, who didn’t believe in it himself, but pushed it as a cheap alternative to real medicine. I won’t go over that again here, but see these stories from Alan Levinovitz in Slate and David Gorski at Science-based Medicine.

Salzberg also points to the apparent impact that TCM has on endangered species such as African rhinos, black bears, and pangolins — an issue that was brought sharply into the spotlight last week when Chinese authorities stunned environmental organizations across the world by reversing a 25-year ban on the use products made from rhino horn:

Why Did China Just Lift a 25-Year Ban on Rhino Horn?Article Oct 31, 2018

Why Did China Just Lift a 25-Year Ban on Rhino Horn?Article Oct 31, 2018

Doctor Liu, an ophthalmologist at Ningxia People’s Hospital in Yinchuan who has studied and worked in both “Western medicine” and TCM, has a more nuanced view. “We have to learn from both,” he says. “Chinese medicine is like Western medicine: doctors study for years, and observe which treatments are most effective. When evaluating a patient, the doctor considers their symptoms and medical history to best prescribe the needed treatment.”

Dr Liu broadly agrees with Salzberg’s point that “there’s just medicine–if a treatment works, then it’s medicine”, saying that in China and the West alike “doctors just try to find the best way to treat their patients.” However, he argues that the “theory of the body” behind the two practices are different, mentioning that TCM has always placed more emphasis on lifestyle, exercise and diet changes as part of the treatment, relying not only on the “medicine” itself, an approach that doctors in the West are increasingly adopting.

A slide from the WHO announcing the inclusion of TCM in the ICD

Dr Margaret Chan, the Hong Kong-born former head of the WHO, has made a similar point, arguing in a keynote speech in 2016 that the practice can help “reduce the burden on health services” around the world because it is “an approach that stresses prevention as well as cure”.

What of Salzberg’s repetition of Nature magazine‘s claims that TCM is “unscientific, unsupported by clinical trials, and sometimes dangerous: China’s drug regulator gets more than 230,000 reports of adverse effects from TCM each year”?

“Of course people will experience side effects,” argues Dr. Liu, adding that “from my experience the side effects from TCM are much less severe than Western medicine. There have been a few cases of exported TCM containing harmful chemicals, so now TCM has a bad reputation in many Western countries. But these are chemicals and preservatives added by certain companies.”

Related:

Landmark Exposé Links TCM to Liver DiseaseArticle Aug 02, 2017

Landmark Exposé Links TCM to Liver DiseaseArticle Aug 02, 2017

The practice of adding non-herbal chemicals is apparently not restricted to exports, however. TCM toothpaste manufacturer Yunnan Baiyao — which has a history dating back to the late 19th century — recently made headlines (link in Chinese) in China after it was sued for allegedly selling products that contained tranexamic acid.

Regarding the slaughter of endangered animals that Salzberg links to TCM practices, Dr. Liu is adamant that “it’s not TCM’s fault”, arguing that official practitioners don’t endorse the use of such products. “These animals are linked to having healing properties. For example, even a very small amount of the rhino horn when processed and made into a soup can help people with high fever. But people don’t use these any more. It’s illegal. Of course there will be people who will break the law, but it’s illogical to blame TCM.”

Related:

Who Uses Chinese Medicine, and Why?Article Mar 24, 2018

Who Uses Chinese Medicine, and Why?Article Mar 24, 2018

From Dr. Liu’s perspective, such incidents are unfortunate but not representative of a practice that has existed for centuries. “You can’t ignore the thousands of years history of the use and continued improvement of TCM,” he states. “TCM is not a scam. Obviously this guy [Salzberg] doesn’t really know about TCM, he’s just fishing for things wrong with it. You have to analyze [these issues] from a bunch of different angles, not just one.”

Maybe so, but with question marks over TCM’s lack of scientific credentials likely to persist and China’s recent reversal of bans on the use of tiger and rhino products stirring up anti-TCM sentiment in some quarters, don’t expect TCM’s rise on the global stage to be cured of controversy any time soon.

—

Cover photo by Antonika Chanel on Unsplash

Related:

Why Did China Just Lift a 25-Year Ban on Rhino Horn?Article Oct 31, 2018

Why Did China Just Lift a 25-Year Ban on Rhino Horn?Article Oct 31, 2018

Theory and Practice: Observing Modern Clinical TCMArticle Jul 13, 2017

Theory and Practice: Observing Modern Clinical TCMArticle Jul 13, 2017

Yin and Yang for Dummies: Dipping a Toe into the Theory of TCMArticle Jul 05, 2017

Yin and Yang for Dummies: Dipping a Toe into the Theory of TCMArticle Jul 05, 2017