It’s 9 AM on a Saturday, and 32-year-old Liu Tong has watched the assigned film and rehearsed the script multiple times. Now, she holds her script expectantly and sits among a group of movie ‘listeners.’ She is ready to tell them a movie.

Liu has been a movie narrator for the visually impaired for nine years, and she is a regular volunteer at Heart Cinema (xinmu yingyuan 心目影院) in Beijing. It’s a community program run by Hongdandan Education and Culture Exchange Center, a nonprofit dedicated to serving people with visual impairments.

China has more than 20 million people with vision disabilities, according to a recent national survey. In recent years, many cities in China have been trying to make movies accessible for all.

Shanghai has about 50 commercial movie theaters that provide headphones with a specific narration channel for the visually impaired. Still, accessible films heavily rely on local communities and volunteer groups, especially in smaller cities.

Founded in 2005, Heart Cinema is reportedly the first cinema of this kind. Volunteer narrators introduce, describe, and explain unidentifiable information such as characters, movements, and scenes between lines to help the visually impaired understand the movies.

More than a decade later, more and more young people are volunteering and helping to expand the service to other cities in China and online.

The Universal Love of Film

Shi Xiufeng, 37, a freelancer based in the city of Wuxi in East China, started the ‘Blind Hollywood’ project in 2015.

Shi and two of his friends recorded voice-overs for films and sent the audio clips to audio apps, libraries, and radio stations across the country. On the Chinese audio app QingTing FM, the program has gotten 842,000 listens thus far.

“Although we cannot restore their lost vision, it is still meaningful to let the visually impaired enjoy a movie in a more smooth, comprehensive, and clear way. After all, you can listen to stories without watching the video,” Shi says.

Unfortunately, they ran out of budget and had to pause the project in June last year, he tells RADII, but they hope to resume it in 2023 after raising enough money. So far, they’ve narrated 30 films.

“Many people like great films, even though they can’t enjoy the light,” reads the ‘Blind Hollywood’ profile on QingTing FM. Image via QingTing FM

In Southwest China, Wang Yifan, a 30-year-old stand-up comedian, has been a volunteer at Heart Light Cinema (xindeng yingyuan 心灯影院) in the city of Kunming for about two years. Wang learned about the program when he was at a low point in his life: He’d lost his job and had broken up with his then-girlfriend.

“I was alone in the city. I was in a very poor physical and mental state, and I even thought about killing myself,” Wang says.

The cinema and its founder inspired him immensely, and he was once again able to delve into his passion for sharing and discussing films with others as he did as a film student.

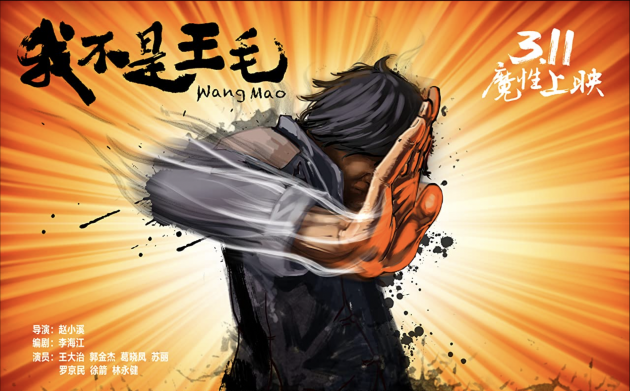

Wang started volunteering to work himself out of the low point that he found himself at the time. The first film he narrated independently was a 2014 Chinese comedy movie called Wang Mao. The genuine reaction and warm applause from the audience had a deep impression on him.

“I felt that I played a very important role in their lives, which greatly encouraged and fulfilled my life,” he says.

Now, two years later, Wang is still volunteering and has inspired other comedians in the city to participate as well.

A poster for Wang Mao, the first film that Wang Yifan narrated. Image via IMDb

To Tell a Movie Well

It requires skills and practice to explain a movie well, narrators say. While narrating in real-time in front of the audience, volunteers tell RADII that it’s difficult to explain everything in between dialogue without pausing or interrupting the film.

Often, it’s a judgment call that narrators have to make on the spot. Generally speaking, visual elements need to be explained, such as transition scenes, ambiance, action, and the appearance of characters. In contrast, voices and sounds are more self-explanatory and comprehensive for the visually impaired.

“Do not cover the dialogue, use accurate words, keep your pace with the rhythm and sound effects of the movie. This is the best narration,” says Wang, who has narrated 16 films that feature at Kunming Heart Light Cinema.

Wang adds that people with visual impairments tend to be sensitive to sounds. He says they can capture details and emotions in the sound, so he avoids over-explaining and leaves room for imagination.

Wang Yifan (left) is narrating a film at Heart Light Cinema. Image courtesy of Wang Yifan

Heart Light Cinema hosts weekly film screenings in Yunfang Museum’s conference room. With the lights off, narrators stand in front of the screen and add improvised explanations.

Qu Shuaishuai, a university student who has been a volunteer narrator since September last year, thinks it is a better approach than reading from a script.

“Getting rid of the text allows your emotions to come out more naturally,” he says. “Voices help the visually impaired visualize images in their mind. If we read off a script, we may lose the emotion in our expression.”

Qu says that previously he had to watch a film seven or eight times, write down a script frame-by-frame, edit the text, rehearse, and eventually recite the text. But after doing this several times, he no longer needs his notes. It has become natural for him to translate visuals into words when he watches a film.

Lan

However, that doesn’t work for everyone.

Liu tried going off-script once, but she was unable to catch every detail in time. As a result, the audience didn’t fully understand the film.

“You have to write down something, at least the characters’ names, relationships, and appearances,” Liu says. “You can’t write nothing down. That is absolutely not OK.”

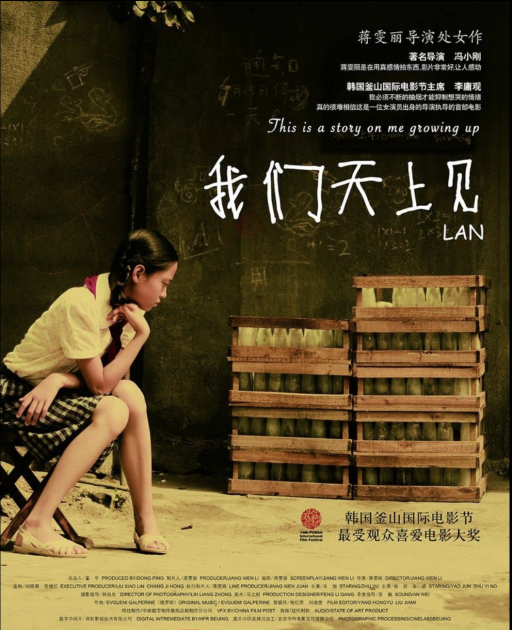

She used to take months preparing for a film. Liu’s first script was for Lan, a 2009 autobiographical film directed by Chinese actress Jiang Wenli. It took her half a year to finish the script. Now, after 63 narrations, she can get ready in four days.

A poster of Lan, the first film that Liu Tong wrote a script for. Image via IMDb

Although she reads from a script, Liu tries to sound natural and sometimes improvises during her narration.

“I try to tell the movie as if I’m whispering to an old lady,” she says, referring to the training she received at the cinema. “That sounds comfortable to the visually impaired.”

Each film is different, but volunteers generally say that literary films with fewer characters and a slower pace are easier to narrate. Wang says he wants to narrate The Godfather, but the interpersonal relationships shown in the movie are too complex to explain.

Shi’s program somewhat solves this problem by using editing techniques. With a background in dubbing, he tries to make his movie narrations audibly refined for people with visual impairments.

You might also like:

How a Blind Man Mastered an “Impossible” Violin PieceZhang Zheyuan has no memory of vision. Nonetheless, he has achieved mastery over his violin. His story will inspire you to live with fearless convictionArticle Dec 14, 2019

How a Blind Man Mastered an “Impossible” Violin PieceZhang Zheyuan has no memory of vision. Nonetheless, he has achieved mastery over his violin. His story will inspire you to live with fearless convictionArticle Dec 14, 2019

Shi and his team synthesize the voice-over into the movie’s sound clip and post-edit the audio file. Sometimes, it means extending the gap between dialogue to fit narrations in, but Shi’s editing skills mean that he can make these gaps subtle.

He also gives a short intro at the beginning of each episode to explain unfamiliar notions. On average, each film narration takes 300 hours to produce.

Once they resume the project, Shi says, the first film they want to narrate is Inception. He reckons that the movie is hard to explain, but his listeners need good narrations for great films.

“One of our listeners told us that he’s a Marvel fan, but he couldn’t enjoy Marvel movies after he lost his vision in an accident, and he was very excited to find our narrated Iron Man,” Shi recalls. “This is probably the meaning of our work.”

More Than Movies

For people with visual impairment, listening to films is a cultural event and a social one.

Visually impaired people and people with other disabilities seldom go out in China because public facilities are not accessible enough in many places. Aside from film narrations, local community groups also provide training on assisting people with visual disabilities.

The community theaters give visually impaired people a reason to get out of the house, and volunteers wait at bus stops and help them walk the final stretch to the cinema.

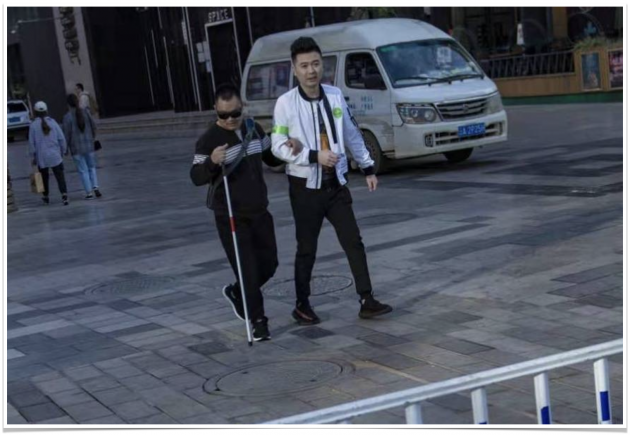

“You help by leading them as they walk, serving as a white cane,” Wang says.

He tells RADII that to approach people in need, volunteers should greet, identify themselves, and at the same time touch the person’s lower arm or hand using the back of their own hand. They should give clear voice instructions and avoid frequent body movements.

Wang Yifan assists a visually impaired person to cross the road. Image courtesy of Wang Yifan

As a comedian, Wang also performs stand-up for the visually impaired. He says that the audience is very open to new things.

“They’re very encouraging and accepting. They immediately applaud whenever we pause,” he says. “I’m not sure how much they understand, but the laughter and applause keep going.”

Wang Yifan also does stand-up comedy for the visually impaired. Image courtesy of Wang Yifan

The volunteering experience is also meaningful for narrators, many say.

“It’s a shared process in both ways,” Liu says. “We narrators have also gained a lot from this. For example, we can improve our language skills, get another perspective on the film, and have a window to stay in touch with the outside world.”

Born with cerebral palsy, Liu has problems moving and has to use a wheelchair to get around. She regards volunteering in the theater as a channel to interact with others and appreciate film art.

Liu Tong narrated a film online on October 9. Screengrab via the online screening

Though Beijing Heart Cinema also offers online film narrations, Liu prefers narrating in person. She enjoys chatting with the audience.

“[Online narration] is like talking to myself. It’s easy to get tired after a while,” she says. “Face-to-face is just different from speaking behind a phone screen.”

Liu says that her goal is to tell every movie well and keep doing it.

“I like movies. I like to do this. You can do anything if you want,” Liu says. “If you really put your heart into it, you don’t think too much but just keep doing it.”

Cover photo by Ryoji Iwata on Unsplash