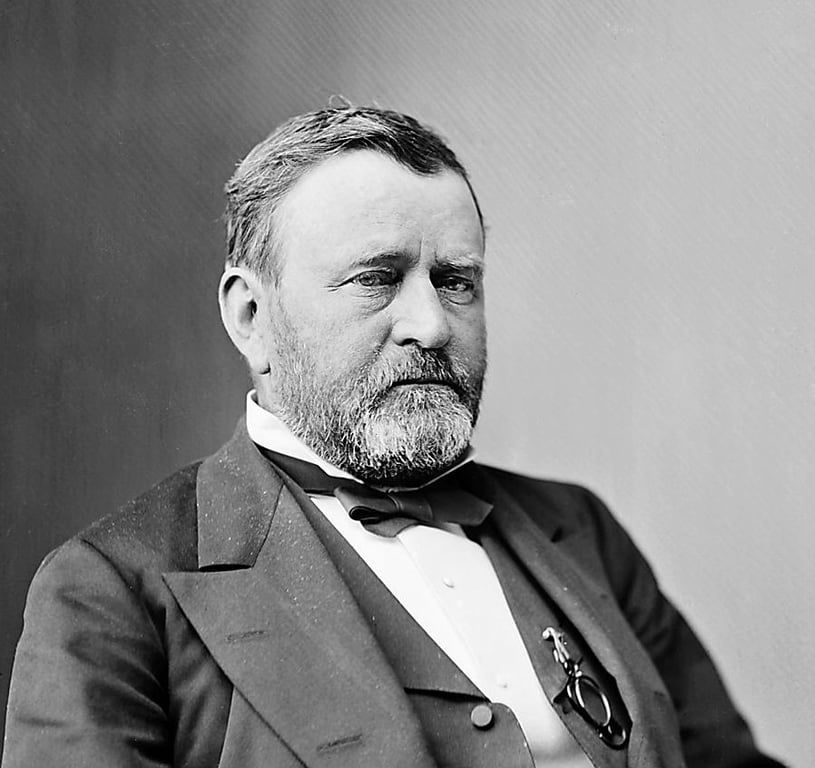

This is Part 2 of a two-part series on Ulysses S. Grant’s 1879 tour of China. Part 1, tracking Grant’s arrival in Guangzhou and procession to Shanghai and Tianjin, is here:

When Ulysses S. Grant Met General Li (Part 1)Article Jan 21, 2018

When Ulysses S. Grant Met General Li (Part 1)Article Jan 21, 2018

Once in Beijing, Grant shifted from tourist to amateur diplomat.

At the Zongli Yamen, the office which coordinated the Qing government’s dealings with the foreign powers, Grant met with Prince Gong. Prince Gong was the uncle of the Guangxu Emperor, then only a boy, and was considered the public face of the court, though much of the real power was held behind the scenes by the emperor’s aunt, the Empress Dowager Cixi. Grant had declined the punctilio of a court visit with a seven-year-old and instead sat for an initial hour-long conversation with Prince Gong. The first meeting between the two was stiff and formal, with the flow of conversation slowed by sideline discussions of translation and nuance. Nevertheless, the colloquy was remarkable in its prescience.

Prince Gong reminded his American guest, “If the world considers how much China has advanced in a few years, it will not be impatient. I believe our relative progress has been greater than most nations. There has been no retrocession, and, of course, we have to consider many things that are not familiar to those who do not know China.”

Prince Gong reminded his American guest, “If the world considers how much China has advanced in a few years, it will not be impatient”

Grant replied, “I think that progress in China should come from inside, from her own people. I am clear on that point. If her own people cannot do it, it will never be done. You do not want the foreigner to come in and put you in debt by lending you money and then taking your country.”

Grant’s response showed an understanding of his imperial hosts’ predicament that was more nuanced than many of the diplomats serving on the China coast. Nevertheless, in a follow-up letter sent to the US Consulate General in Shanghai, Edward Beale, Grant qualified his optimism over China’s prospects for development. “I would not be surprised,” Grant wrote Beale, “if I should live so long, to hear more complaint of Chinese absorption of the trade and commerce of the world than we hear now of their backward position. But before this change begins to show itself there will be a change of dynasty.”

“I would not be surprised, if I should live so long, to hear more complaint of Chinese absorption of the trade and commerce of the world than we hear now of their backward position. But before this change begins to show itself there will be a change of dynasty.” — Ulysses S. Grant in a letter to Edward Beale, US Consulate General in Shanghai

Prince Gong also had something of even greater importance to discuss with Grant. The Meiji government had begun to expand its control over the island chain which ran between the Asian mainland and the southern tip of Japan. This included both Taiwan — then officially a prefecture of Fujian Province — and the Ryukyu Islands, which had for many centuries been an independent kingdom.

The Ryukyu Islanders maintained their precarious position, sandwiched between two larger neighbors, by sending tribute to both the Qing court and to Japan. This awkward arrangement came to an end in 1879, when the Japanese announced their intention to annex the islands outright.

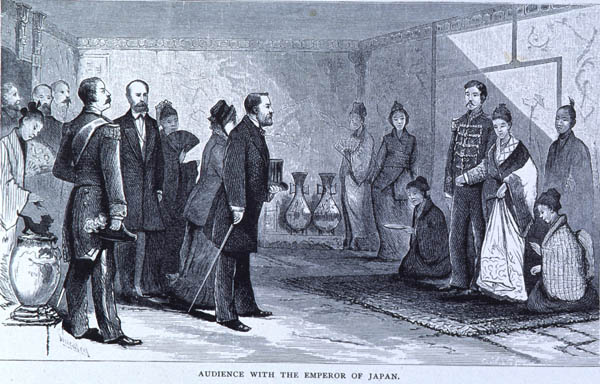

Grant in Japan (source)

Prince Gong urged Grant to try and get the Japanese to drop their plans to formally annex the islands when Grant visited Japan later that summer. Grant demurred and attempted to temper expectations, reminding Prince Gong that, “Here I am a traveler, seeing sights, and looking at new manners and customs. At home, I am simply a private citizen, with no voice in the councils of the government and no right to speak for the government.”

“We have a proverb in Chinese,” the Prince deftly countered: “‘No business is business’ — in other words, that real affairs, great affairs are more frequently transacted informally.”

Moreover, Prince Gong, like many modernizers in China, possessed a great deal of faith — some would say too much faith — in the power of international law.

“If there is any force in the principles of international law as recognized by your nations the extinction of the Loochoo sovereignty is wrong and one that other nations should consider,” Prince Gong told Grant when they met again that week, this time at the US Consulate in Beijing.

Prince Gong, like many modernizers in China, possessed a great deal of faith — some would say too much faith — in the power of international law

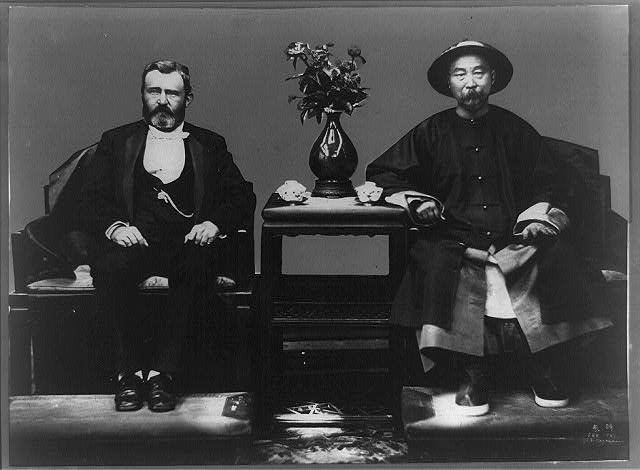

Li Hongzhang was blunter. During a final conversation he had with Grant as the latter prepared to sail to Tokyo, Li argued that the actions of Japan called for the intervention of outside powers. Otherwise, the Qing official dryly noted, “there was no use of that international law which foreign nations were always quoting to China.”

Ultimately, Grant failed to convince the Japanese government to turn back the clock on the status of the Ryukyu Islands. Instead, Grant persuaded his Japanese hosts to agree to the formation of a joint commission to investigate the competing territorial claims. The commission never happened, but it’s likely that Grant’s involvement helped calm tensions at a time when both parties were preparing for war.

Grant returned home from his world tour in September of 1879 and began a barnstorming whistle-stop tour of the United States in a stealth campaign for the Republican nomination in the 1880 presidential election. He would not be successful, with the nomination going to relative dark horse James Garfield. Grant died a few years later, in 1885, of throat cancer. When he died, Grant was celebrated as a national hero, and while his reputation would wax and wane with each generation of historians, he remains the first US president to visit China.