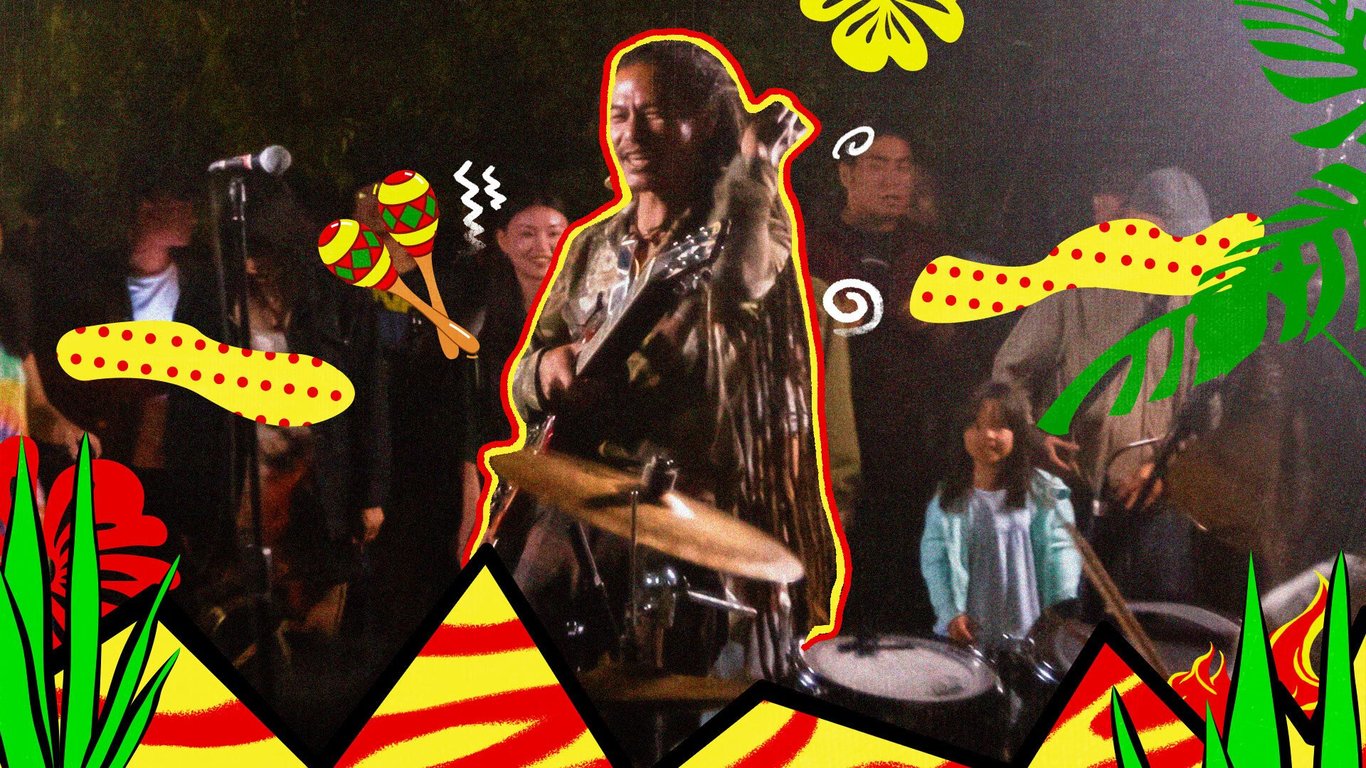

Into the Night is a series exploring China’s vibrant nightlife and music scene and the roster of young people that make parties in the country so damn fun. This story introduces the unexpected reggae scene that thrives in Southwest China’s Yunnan province.

This might come as a surprise to some, but China and reggae music have a strong connection. The Chinese-Jamaican community, which first settled in the Caribbean nation during the 19th century, significantly impacted the roots of reggae music. Some formative members of this Chinese-Jamaican community include Byron Lee, who first introduced electronic bass to reggae music, and ‘mother of reggae’ Patricia Chin, who founded the seminal Randy’s Studio 17.

Lesser known, however, is the community of reggae musicians residing in China’s southwestern province of Yunnan, which borders Southeast Asian countries such as Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam.

Reggae bands like Kawa and Shanren have achieved national fame for fusing local music elements with reggae and creating sounds that derive influence from Jamaican music while also honoring their cultural roots.

“We have a similar skin tone, we live on the same latitude as Jamaica, our traditional rhythms are similar, and Wa villages look like the scenes you would see in a Jamaican slum,” says Lao Hei, the producer and guitarist of popular Yunnan reggae band Kawa, in an interview with RADII.

“Wa people live a simple life. They are free when it’s not farming season. They like singing and dancing. They drink moonshine during festivals and holidays, and they love to dance their traditional dances.”

The Wa people are one of 56 ethnic minorities recognized by the Chinese government. The ethnic minority group is scattered mainly throughout Southeast Asia, especially Myanmar, and China’s Yunnan province.

“There’s an identification with reggae. It comes with a kind of national pride of the Wa. It’s being expressed through reggae as an identity. It’s a big way of expressing what it is to be Wa,” Sam Debbel, founder of the music label Sea of Woods, tells us.

“Ethnic minority groups that grow up dancing, they have a better sense of rhythm, because if you separate dance from music, it’s gonna be a problem. The Wa rhythm that they have is a binary kind of swing. You can see how they would naturally take to it; that’s why they make good reggae musicians because the rhythm is very natural.”

Of course, Wa people are not the only ones engaging with reggae music. Yunnan is one of China’s most diverse provinces, home to 25 of China’s ethnic minority groups.

Puman, another popular reggae band in Yunnan, put out a track titled, ‘Bulang Beauty’ as an ode to the Bulang or Blang people. Tan Gaosheng, the band’s lead vocalist and guitarist who is Bulang, tells us, “You can include different elements from different ethnic minorities like Wa or Bulang or De’ang, Naxi, Dai or Yi people — all of their cultural elements can be made into reggae.”

“Bulang folk music and reggae are a good fit. When I was young, there was a waterwheel by the river, and there was a device that husked rice under the waterwheel. If you put your feet on it, it would make a backbeat rhythm. Reggae also has a strong upbeat.”

Reggae music made its way to China in the same way that most international music did in the 1990s — via dakoudai (打口带), which loosely translates to ‘cut cassette tapes.’ The term denotes how tapes and CDs usually had chunks cut out before being sent to China as waste; vendors then sold them illegally on the black market.

“The first time I bought a dakou tape was around the late 1980s or the early 1990s. I went to the record store, and I saw some tapes with cuts on them,” reggae guitarist Zi Rang tells us.

“I thought it was very strange and asked the shop owner what those were. The owner said those were dakou. I spent about 15 RMB; it was very expensive for me as an elementary student. This was the first dakou that I bought,” adds Zi while showing us a picture of Grand Daddy I.U., a rapper during the Golden Age of Hip Hop in New York City.

The musicians RADII spoke with share one thing in common: a feeling of being drawn to reggae music despite not knowing what it was.

Tiger, a drummer and bassist with Kawa, says, “One day, I searched the internet for bands in Yunnan, and then Yunnan reggae popped up. I clicked it, and the first song was from Kawa called ‘Get Drunk’ (干酒醉). Wow, I was like, this is amazing, I’m gonna do this someday.”

Fu Xugang, a guitarist with Puman, tells us of his first encounter with reggae: “I went to my friend’s house, and he played a Bob Marley concert, but I didn’t know what reggae was. I just felt the music was relaxing. It sounded so good.”

Zi Rang shares a similar sentiment when he says, “There used to be a lot of bars in Dali [a town in Yunnan province]. Even at that time, people played Bob Marley and put up his photos in the bar, but we didn’t know who Bob Marley was. I didn’t know it was reggae either, but I loved it. Ever since then, I’ve liked reggae.”

Fu Xugang sums it up nicely when he says, “We all live on the same planet. We are different people, but the earth is our root, so it doesn’t matter where you live, whether it is as part of rasta culture or as a minority in Yunnan, we are all the same.”

All images from ‘The Chinese Reggae Scene You Didn’t Know Existed,’ episode one of RADII’s mini-doc series ‘Into the Night’