Sun Wu Kong, the monkey born of stone.

As the legend goes, he became king of the monkeys, possessing supernatural strength and the ability to clone himself, transform his shape, and travel by cloud. However, after he formed alliances with powerful demons, the gods offered the monkey a job in heaven in order to keep closer watch over him. But it was the lowest-ranking position, and upon realizing this, the monkey rebelled and proclaimed himself “The Great Sage, Equal of Heaven.”

Though the deities tried again to appease the monkey, his exclusion from a royal banquet was the final straw. In rebellion, he consumed the Peaches of Immortality and Pills of Longevity before single-handedly defeating the Army of Heaven, four heavenly kings, and Nezha. Just when it seemed like the monkey would win, Buddha sealed him in a mountain for five hundred years — only to be freed by the monk Tripitaka on his journey to retrieve Buddhist scrolls in the west.

Related:

How “Ne Zha”, a Revamped Tale from Chinese Mythology, Became the Country’s Biggest-Ever Animated MovieThe movie has smashed box office records and easily surpassed “The Lion King” in Chinese cinemasArticle Aug 02, 2019

How “Ne Zha”, a Revamped Tale from Chinese Mythology, Became the Country’s Biggest-Ever Animated MovieThe movie has smashed box office records and easily surpassed “The Lion King” in Chinese cinemasArticle Aug 02, 2019

Though the story of Sun Wu Kong first appeared in the Song dynasty — it was popularized by the 16th century novel Journey to the West. Attributed to Wu Cheng’en, the tale of the Monkey King’s (mis)adventures and his journey towards enlightenment has become one of China’s four great classic novels.

Historical Chinese texts don’t often translate into multimillion-dollar film franchises and fan cults — especially in the global market. Yet that’s the situation with Sun Wukong, who continues to be the subject adaptation after adaptation for stage, film, and TV, and whose likeness has graced everything from Shanghai Film Festival posters, to an exhibition about Artificial Intelligence, to a themed hotel, to a China United Airlines plane — and all that’s just from last year.

To find out how Sun Wukong transformed from literary classic to contemporary cultural icon, we did a little digging.

Rebel? More Like Revolutionary Hero (1941-65)

Wu Cheng’en’s novel inspired countless spinoff stories and theater productions in the following centuries. However, it’s the switch from stage to screen that deserves attention, one of the Monkey King’s major transformations. In the context of a tumultuous China — ravaged by Japanese occupation, civil war, and the construction of a new socialist era — Sun Wukong was reshaped to represent the revolutionaries.

As Hongmei Sun writes in his book Transforming Monkey: Adaptation and Representation of a Chinese Epic, one of the earlier efforts to transform the trickster into a role model can be traced back to China’s first animated feature, Princess Iron Fan (1941). Produced in the midst of WW2, Wan Laiming and his brother made a few revisions to Journey to the West in order to frame Sun Wukong’s fight with the Bull Demon King and his wife, Princess Iron Fan, as a metaphor for the Sino-Japanese war.

In the film, Sun Wukong’s initial failures to retrieve the Princess’ magical fan — which is needed to put out the flames blocking his travel route — are attributed to division among his team. It is only after the trio work together and receive help from the villagers (in the original, it’s heavenly troops) that they are able to fulfill their mission. Historian Sun explains: “The film made it quite obvious that the Monkey King’s victory over the Bull Demon King… is the victory of the Chinese people against the Japanese invasion, thus making the theme of the film ‘all Chinese people must unite for victory against the Japanese invasion.’”

Surprisingly, given its religious and supernatural elements, Sun Wukong’s story survived the next two decades of social upheaval and literary purges. As Mao stressed that literature should serve the people, the Wan brothers made Havoc in Heaven (1965) extra-appropriate for the socialist revolution, glorifying Sun Wukong’s rebellion and eventual victory over the celestial court while cutting out his imprisonment by Buddha. According to Sun, the Monkey King represents the class of farmers rising up against the elites, consequently solidifying his place in contemporary Chinese culture as “the good guy.”

BACK TO THE BOOK (1986)

While Princess Iron Fan and Havoc in Heaven put Monkey King on the silver screen, it was the 1986 TV series Journey to the West that helped him conquer the hearts and homes of Chinese across the country. Broadcasted on October 1, CCTV’s version is praised for being the first production to cover almost all of the 100-chapter novel; season one pulled from the first 74 chapters, and season two, which aired over a decade later, referenced another 25. Because of this authentic interpretation of the classic, plus superb acting from Liu Xiao Ling Tong (六小龄童), who won a Golden Eagle Award for his Monkey King performance, the show became a sensation and has been broadcast on local channels ever since.

The show can be viewed on Chinese state broadcaster CCTV’s YouTube channel.

Granted, it’s not Sun Wukong’s most dramatic transformation. However, the TV version of Journey to the West has played an important role in popularizing the Monkey King as told by the original source material, rather than his nationalistic caricature. Mainstream success at home allowed the Monkey King to mark Asia as his home turf before moving on to other regions of the world.

From Great Sage to Super Saiyan (1984-95)

Any ’90s kid will be familiar with Son Goku, the extraterrestrial Saiyan who searches for Dragon Balls and strives to be Earth’s greatest defender.

But what they may not remember is that their beloved spiky-haired hero is based on none other than Sun Wukong (the similarity of their names should’ve been your first clue). When Goku made his debut in 1984, he was portrayed as a monkey-tailed boy with incredible martial arts skills and superhuman strength. Though he wasn’t covered in monkey fur, he was dressed in monk-like robes and given a length-changing staff and a magical cloud to command — both of which were originally wielded by the Monkey King. Many of the early supporting characters are also reimaginings of the OG squad: Bulma is Tripitaka; Oolang is Pigsy; and Yamcha is Sandy.

when u need an image to both confirm your newly discovered “goku has a tail” knowledge and convey your reaction to this information pic.twitter.com/NgaEqoVOph

— Chris Pereira (@TheSmokingManX) January 11, 2019

Dragon Ball – and especially Funimation’s dub of Dragon Ball Z – not only gave Journey to the West a modern (and less nationalistic) retelling, but helped Sun Wukong travel farther west, exposing new audiences to Asian entertainment. By melding Japanese, Chinese, and Hollywood influences — the series references characters such as the Terminator and Fairy Godmother — creator Akira Toriyama was able to reinvent the Monkey King for a different time period, while maintaining the traits that made the hero so popular in the first place.

If only the same thing could be said about the next set of works.

Sun Wu Kong Gets a Hollywood Makeover (2001, 2008)

After centuries of headlining operas and animes, Sun Wukong would be disappointed to find out that he was passed up for the leading role in two Hollywood productions. In both The Monkey King (2001) and The Forbidden Kingdom (2008), Sun Wukong is relegated to the role of a secondary character, who passively waits 500 years for an American protagonist to free him from stone imprisonment.

Granted, Tripitaka does save him in the original, but what differentiates these movies from the works before them is the focus on the monk’s heroics. Though Tripitaka is the one who often requires rescuing in the novel, the role is reversed here: Nick Orton (The Monkey King) and Jason Tripitakas (The Forbidden Kingdom), both woefully inept at kung fu and just generally mediocre, are somehow the only ones who can save ancient China from certain doom.

The Monkey isn’t useless per se, but when a character shows up for only the first and last few minutes of the movie — as is the case with The Forbidden Kingdom — it’s clear that they are not the real hero. Sun Wukong’s world simply acts as a backdrop for the Americans’ own journey of transformation and self-discovery.

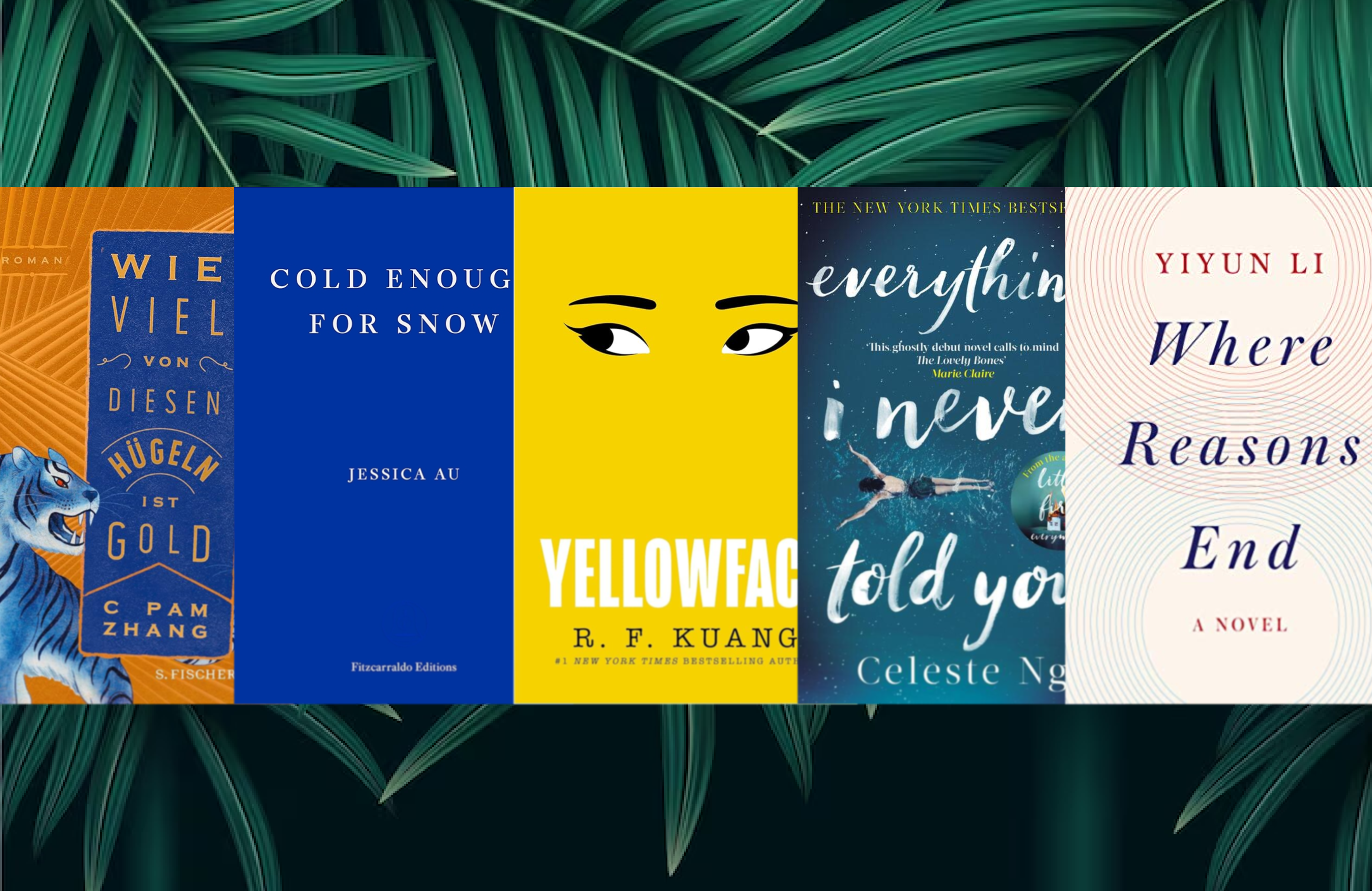

A Signpost to the Asian American Soul (2006)

While early Hollywood failed to give Sun Wukong the spotlight he deserved, American Born Chinese makes the Monkey King pivotal to the plot line. Written by Gene Yang, the graphic novel presents three seemingly disparate stories — that of the Monkey King, along with characters named Jin and Danny — to showcase the author’s personal struggles with race and self-acceptance.

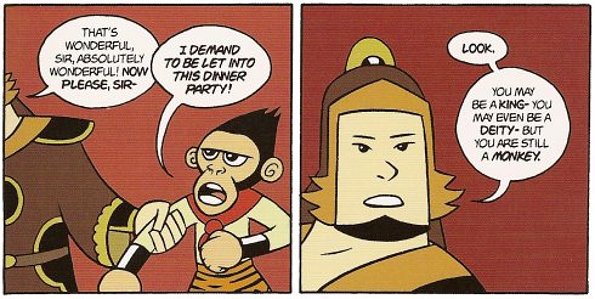

The Monkey King’s tale doesn’t stray too far from the original, but places greater stress on discrimination and identity. After the gods turn him away from a celestial dinner party for being a monkey, Sun Wukong denounces his animal nature, masters new powers, and proclaims himself “Great Sage, Equal of Heaven.” Jin (representing Gene) similarly grapples with being an ethnic minority in a majority-white school, and distances himself from his heritage to better assimilate — to the point of wishing himself into a white boy.

This is where things get interesting. In the final storyline, Danny, Jin’s white alter-ego, has his life disrupted when his Chinese cousin Chin-Kee comes to town. Chin-Kee (yes, “Chinky”) is Yang’s answer to Long Duk Dong, and embodies every stereotype in the book: he’s slant-eyed, bucktoothed, yellow-faced, nerdy, and uncivilized. He represents everything Jin has been taught to associate with and hate about his culture. However, in a twist, Chin-Kee reveals himself to be the Monkey King, having disguised himself to serve as Jin’s conscience — “a signpost to [his] soul.”

In this retelling, the Monkey King serves to help Jin confront negative stereotypes and start embracing his ABC (American-Born Chinese) identity. As Binbin Fu explains in the literary journal MELUS: “The legendary trickster figure has been repeatedly re-imagined by Chinese American writers as a source of cultural strength, a symbol of subversion and resistance and a metaphor for cross-cultural and interracial negotiation.”

…And Then There’s Everything Else

The pop culture iterations are endless. China and Hong Kong continue to create content around Sun Wukong, from animated films like Monkey King: Hero is Back to Stephen Chow’s Journey to the West. (You can catch Kris Wu spitting sutras in the sequel to that one). In Korea, the folk tale inspired a travel show following celebrities around China, as well as a K-drama that puts a romantic spin on Monkey’s quest for immortality.

The cult following is even more pronounced Down Under. After a Japanese production of the Monkey King story was dubbed in English and Spanish (along with The Water Margin, another classic Chinese tale), the TV show attracted legions of fans in countries like the UK, New Zealand, Mexico, Peru, Argentina, and (especially) Australia in the early 1980s. On Monday through Thursday at 6pm, Aussie kids would jam out to the “Monkey Magic” theme song and catch their favorite hero battling bandits and demons – getting their first taste of Asian-style fantasy action.

In 2007, Damon Albarn brought in his Gorillaz co-conspirator Jamie Hewitt to put together a “21st century opera” version of the classic tale. And in 2018, Monkey inspired a Netflix reboot that, while mired in controversy, attests to how the Chinese icon evokes nostalgia even among those abroad.

So how has Sun Wukong survived the test of time? The long answer is that behind the magic is a monkey whose stories of adventure and transformation resonate with audiences of all cultures. He is very human both in his traits — ambitious, impulsive, brave — and in how he is treated, often misunderstood or overlooked. Yet despite his antics, there is a sense of a fundamental goodness that keeps people rooting for him. And with such a complex character comes room for creative interpretation: while some (Hollywood) see merely a comic relief or a foil to Western culture, others see a superhero.

The short answer: Sun Wukong is an immortal after all.