I’m hanging out in Singapore’s Chinatown, on the kitschily-named Pagoda Street. The sights and sounds down the block are what you might expect — hanging red lanterns, golden calligraphic script on restaurant facades, zodiac animals and acupressure salons. In certain ways it‘s reminiscent of my home in Shanghai. But as a whole, the area comes across as plastic, an artificial cultural center that in many aspects seems less authentically Chinese than the Chinatown in Manhattan. In a country of majority Han Chinese ethnicity, the people shopping at the stalls are out-of-towners. Australian, German, and American tourists pick through booths of neon faux-silk Manchu shirts and brass opium pipes.

Your name written in Chinese on a grain of rice, one stall reads. Translation provided! In the midst of all the spectacle, the only real representation of China slinks by quietly unnoticed. Blue collar migrant workers mix bubble tea and sling cheap desserts, straining to overcome Chinatown’s English-only language barrier.

Pagoda Street – Radii China

Singapore’s history is immensely complex, considering its beginnings as a society go back only about two hundred years, and its origin as a modern state only fifty. Sir Stamford Raffles established colonial Singapore in 1819, settling on the island for its ideal location as a port. The next century saw an unprecedented influx of immigrants from the surrounding areas — Indian Hindus, Muslims from across the Malay Peninsula, and merchants from Armenia and Europe all jostled elbows early on in the small but deeply multinational community.

Port of Singapore circa 1900 – WikiCommons

China was no different, with emigrants from the country’s rural provinces arriving en masse in search of job opportunities and money they could send to their families back home. Chinese immigrants arriving in Singapore came from different places, spoke different languages, and ate different food. Teochew, Hokkien, Cantonese, and Hakka Chinese groups mingled together with other Chinese and non-Chinese immigrants. The commonality among them was that they all worked laborious, unskilled jobs, earning them the nickname ku li (苦力) — bitter work, which was later anglicized into coolie. Coolies were the builders, seamstresses, carpenters, and cooks who formed the backbone of early Singaporean society.

Restored historical recreation of an 8 x 8 foot coolie living quarters – Radii China

Gradually things changed in Singapore, and the coolies began to rise in socioeconomic status. Their descendants today constitute the majority ethnic group in the country. After the language of public education was changed to English, the Chinese community followed suit and adopted it over Mandarin and other dialects. Today’s Singaporean Chinese are worldly, multilingual, and often affluent — a far leap from their mainland cousins, the majority of whom speak only one language, face government-imposed limitations on their communication with the outside world, and tend to live in relative poverty outside of major city centers. The gap is widened by the fact that most Singaporean Chinese actively distance themselves from a mainland Chinese identity.

Today, mainland immigrants in Singapore face prejudice, cultural boundaries, and lack of opportunity in a country that was technically built by their ancestors.

“They just come here to take our jobs,” one ethnically Chinese, Singaporean-born taxi driver told me. “If someone will come from up there and drive a truck for half the price, how are Singaporeans supposed to be truck drivers? They have to either match the lower salary, or find a different job. And jobs here are already very tight.”

Despite two hundred years of staggering growth, and the rise of Singapore — a 49 kilometer-long island of a country — to the position of a major Asian Tiger economy, Chinese immigrants find themselves in largely the same outsider position they held in the country’s early years.

The difference is that mainland Chinese in Singapore today generally aren’t unskilled laborers. They’re often highly paid workers in multinational corporations, or academics in research and educational institutes. They’re certainly not coming to work as truck drivers, to make comparatively low wages in a foreign country where the cost of living is far higher than their own. In that sense, the bubble tea-serving tier of Chinese immigrants is in the minority. But while many of the Chinese employed in Singapore hold comfortable, high-paying jobs, cultural and linguistic barriers limit them to functioning in their own spheres.

A Singaporean friend Joshua Tan advised me before I visited Pagoda Street:

In Chinatown, look for instances where Singaporean-Chinese or local Chinese culture contests with mainland Chinese for public space and ownership of Chinese identity. It’s quite fascinating — you’ll notice that many of the most public shopowners and stores have quite a dominant mainland Chinese presence. And Singaporean-Chinese are not so happy about it. There is resistance too, and it appears in unexpected forms and spaces.

The “official history” of Singapore’s Chinese has been beaten to death, and people are going to talk to you about Singapore’s multiculturalism, Chinese architecture, racial harmony etc., which in my view is really regurgitating government propaganda. There are, however, deeply rooted tensions, and tensions between local and mainland Chinese — who really exist in parallel universes — over who has ownership over Chinese identity.

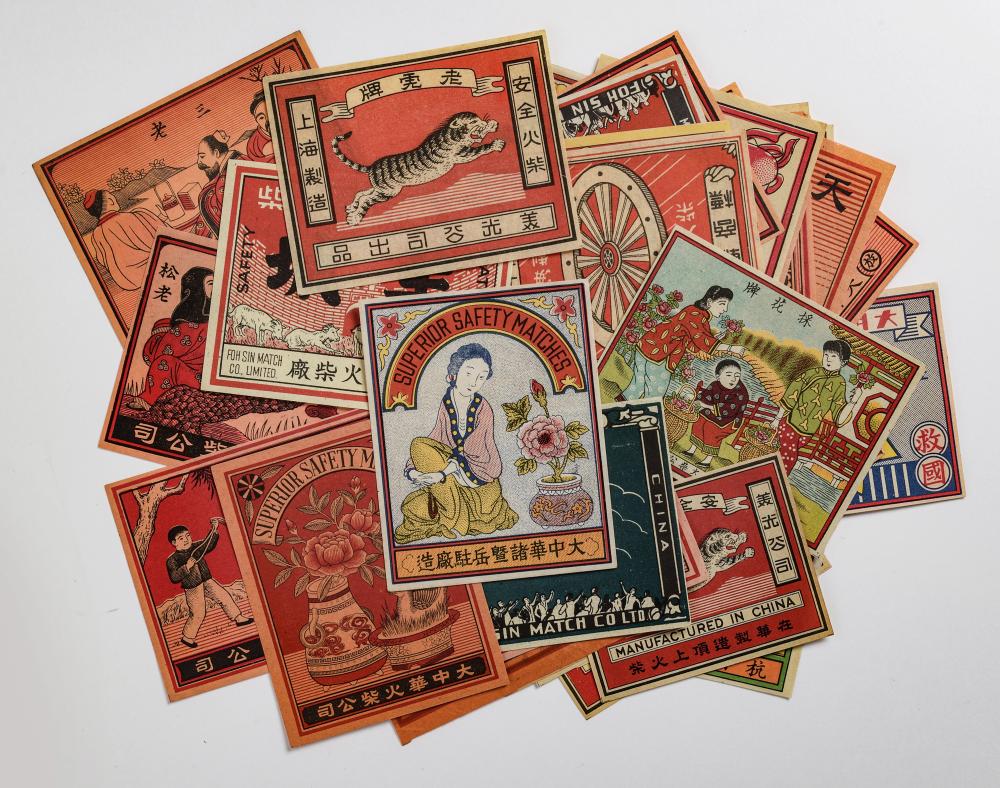

Back on Pagoda Street, I start to understand what he means. I take a tour of the Chinese Heritage Museum, where three young Singaporean attendants set me up on a headset audio guide. Walking through historical recreations of old coolie living quarters, I listen to actors play out fictional Chinese immigrant dialogue in heavy Singaporean-English accents. They briefly address hardships like opium use, but the fresh paint, easygoing storyline, and carefully hung opera posters seem to speak to an erasure of the original immigrant struggle.

Conversations with the elder generation promote the idea of a harmonious, multiethnic Singapore. But young people talk differently about the subject. The millennial lean towards social change has them eyeing their surroundings more critically, and young Singaporean-Chinese readily admit that they possess a standard majority privilege over immigrants, or other minority Singaporean ethnic groups.

Tourist trinkets in Singapore’s Chinatown – Radii China

But as China shoots rapidly through a comparable evolution process of its own, we must question whether that dynamic will remain static. Like Singapore, China is undergoing its own process of rapid economic growth. Foreign money and influence are both flooding into China’s borders at an unprecedented rate. China and Singapore’s governments are comparable — largely uncontested dictatorial powers that steer the overall direction of the country, with Singapore’s government constituting a de facto one-party state.

With China on the rise, and with a greater segment of the population learning English than ever before, it could soon find itself in the same international, financially-empowered position as Singapore. Only time will tell when that dream might be realized, or where Singapore will be when it happens. Until then, the fight continues within Singapore’s borders, the two nationalities both contesting for the right to govern Chinese-ness on the island.

Photos by Adan Kohnhorst for Radii China