As a kid growing up in ‘Hongcouver’ in the 1980s, Cantonese was so prominent that I thought Cantonese was the only language Chinese people spoke. Our family spoke Cantonese at home with Cantonese-speaking mahjong friends while eating chicken rice and watching Chow Yun Fat and Steven Chow movies.

It was only years later, when more Mandarin-speaking immigrants arrived in Vancouver, that my friends and I realized, jokingly, “Hey, that Chinese girl over there is speaking with a lot of Sh-sh-sh’s and ar-ar-ar’s!” My Japanese friend Junji quickly understood that learning Mandarin (known in Chinese as Putonghua) was a prerequisite to meeting more romantic partners from Asia.

Cantonese is incomprehensible to a Mandarin speaker, and vice versa. The spoken word is different, and the characters vary depending on whether they are written in the simplified form of the Chinese mainland or the traditional form like in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

When I moved to Hong Kong shortly after the handover in 1998, I barely heard any Putonghua spoken in public. My father, who grew up in Hong Kong in the 1950s, felt the British colonial government purposely discouraged the masses from learning Putonghua to sow divisiveness between Hong Kongers and Chinese mainlanders.

After the handover, however, the Hong Kong government and businesses started to promote a ‘biliterate and trilingual’ society. This meant being biliteral in English and Modern Standard Written Chinese and trilingual in spoken Cantonese, Putonghua, and English.

Business and government leaders were touting the door-opening opportunities of learning Putonghua, doing business with China and integrating Hong Kong into the Pearl River Delta. I vividly recall an Australian HR director of an investment bank who scoffed at a job applicant’s resume because it indicated she couldn’t speak Putonghua but was fluent in Cantonese.

Suddenly, for ambitious 22-year-olds like me at the time, Putonghua was a means to get rich and to climb the new gold mountain, not just a way of crooning Jay Chou songs at a karaoke box.

Maggie Lee, a 40-year-old environmental activist who teaches Hong Kong-style Cantonese to native Japanese speakers in Hong Kong, says, “My students were motivated to learn Cantonese so that they can better communicate with locals.”

Although interest in learning Cantonese has declined, Lee says, “There is a wider availability of Cantonese learning tools online now than 15 years ago.”

This thought reminds me of an amusing story from roughly 15 years ago involving a friend who was learning Cantonese and only knew how to say ‘moumantai.’ When I asked him how he knew moumantai (無問題,) which means ‘no problem,’ he said it was the title of a Japanese movie about a man whose girlfriend sets off to Hong Kong to become a receptionist for her hero, Jackie Chan.

Fast forward to 2014 in North America: It was while registering for her language placement tests at Stanford that Samantha Wong, a Stanford grad from the class of 2018 and former executive director of The Stanford Daily, realized that Cantonese, the language she spoke as fluently as English, wasn’t listed as an option.

As Wong notes in a 2017 article, “Part of the reason why I chose to attend Stanford was that I got a brochure from the language department during Admit Weekend, listing Cantonese as one of its offered languages.” Strangely, the language department informed her that Cantonese conversation courses do not fulfill the language requirement.

The reason for this certainly wasn’t tied to the number of Cantonese speakers worldwide.

“There are an estimated 80 million Cantonese speakers across the world. In the U.S. alone, according to the U.S. Census, 458,840 people speak Cantonese and 487,250 speak Mandarin. There are more people who speak Cantonese in the U.S. than most of the other offerings in the language department that count toward the language requirement, such as Hawaiian (26,205) and even Japanese (449,475),” explains Wong.

Part of the reason for a declining interest in Cantonese is that many parents in the U.S. teach their children Mandarin, partly because they don’t want their children to be left behind if they decide to do business in China as adults.

As a result of decreased enrollment, bilingual schools and extracurricular classes across America have stopped offering Cantonese courses.

I spoke to Professor Cheung Sik Lee, Samantha’s former Cantonese instructor at Stanford, and discovered that although she retired from Stanford in August 2021, she launched the Cantonese Alliance in September 2021 to save the Cantonese language.

“The need to preserve Cantonese has become very urgent as the structural support for Cantonese both here in North America and in China has been eroding. Our focus is on Cantonese heritage speakers, but we also welcome other speakers, such as Mandarin speakers. It’s a great way to promote mutual understanding and respect,” says Cheung.

When asked how she will promote the Cantonese Alliance, Cheung responds, “We plan to promote host concerts that will bring together musicians who have migrated from Hong Kong to North America. One group has already started Vantopop in Vancouver. In addition, the Alliance will be crowdfunding so that it can provide grants to support community schools, content creators, immersion Cantonese learning, research, and advocacy.”

Cheung expects the Cantonese Alliance to have a similar mix of students as her course at Stanford:

“My students at Stanford were mostly heritage speakers, from about 90% in 1997 to about 60% in 2021.”

She adds that many of her students have fostered strong connections within the Cantonese community.

Joceline Yu, one of Cheung’s students and a Stanford graduate from the class of 2021, explains, “I wanted to learn from my grandmother about her family’s life under imperial Japanese occupation. I wanted to understand the funny jokes and personal anecdotes of my family members’ previous lives in Guangzhou that were shared at the dinner table. I wanted to be able to talk with the uncles and aunties at the 99 Ranch hot deli section and order a whole roast duck all on my own, all in Cantonese.

Yu adds, “All of these conversations that I yearned to be a part of demanded a stronger command of Cantonese that I didn’t have, so I decided that improving my Cantonese was an absolute necessity for me.”

Cheung tells RADII that the number of Mandarin speakers enrolled in her Cantonese courses at Stanford gradually increased over time, with students choosing to learn the language for various reasons.

“Mandarin speakers wanted to improve their Cantonese pronunciation so that they could sing better or watch Cantonese movies and dramas without relying on subtitles. A small number of students took my Cantonese courses because they had accepted internships or jobs in Hong Kong, while others were motivated by other reasons, such as being in a relationship or marriage with a Cantonese speaker,” she says.

Cheung notes that for folks considering becoming Cantonese instructors, the Cantonese Alliance will offer a series of workshops for teachers and content creators to bring creatives together and build a supportive community.

She also stresses the need for standardized Cantonese language education, stating, “We need to standardize Cantonese language education if we want to gain respect for Cantonese language education, for example, defining the proficiency standards for each level, doing needs assessments, and designing curricula.”

Maggie Lee, who is now Asia Pacific Lead for Global Traceability at World Wildlife Fund, says of her recent trip to Hong Kong, “I found that there were more non-native speakers of Cantonese and far more ‘unified’ terminology — terms that sound awkward when said out loud in Cantonese, but because they are official in China, Hong Kong had to adopt them — than I remember from 2020.”

For myself, having returned to Vancouver for several years, I feel a deep sense of nostalgia whenever I hear Cantonese being spoken on the streets, especially in the neighboring city of Richmond, where 54% of the population identify as Chinese.

Nostalgia aside, my knowledge of Cantonese has helped me close deals at work. Now, when clients ask me if I can speak Cantonese, I say, “Mou man tai!” with a cheesy smile.

For more information on the Cantonese Alliance, reach out to Cheung Sik Lee, Ph.D., at [email protected]

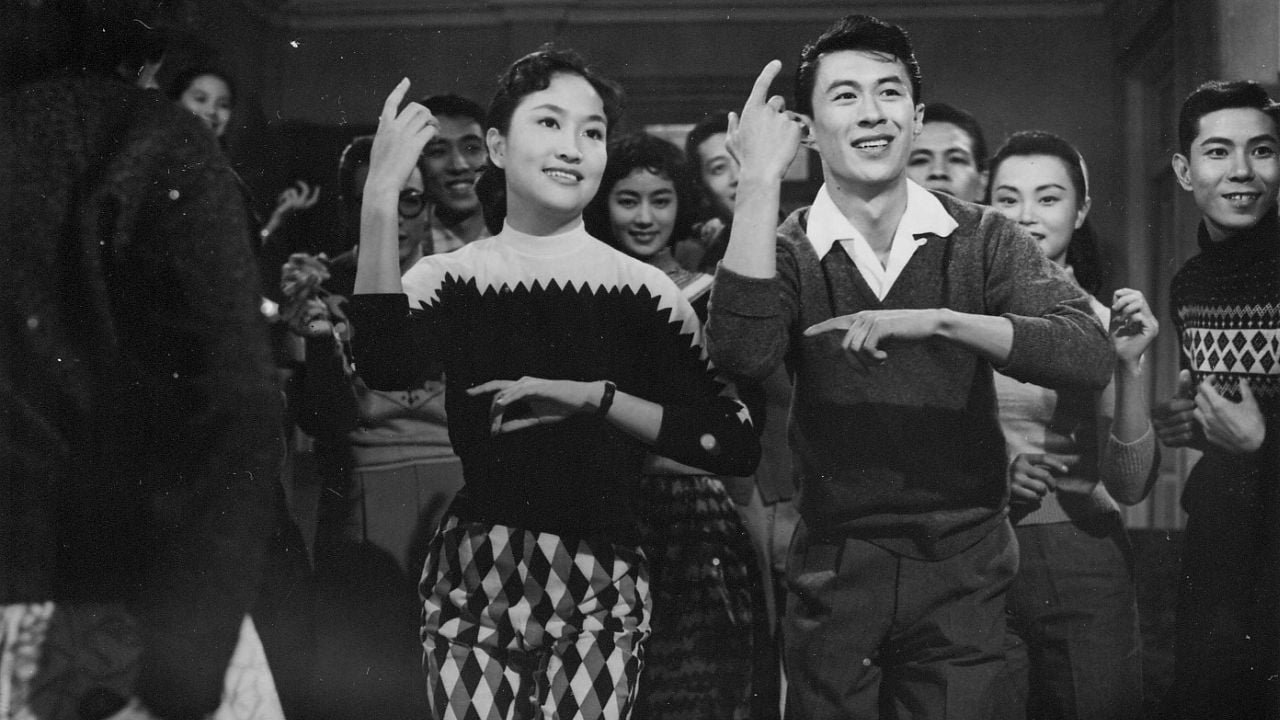

Cover image via Depositphotos; other images via the Cantonese Alliance