China’s food delivery culture is impeccable. Between the reliability, the vast spread of cuisines and discounts, and the gamification of coupon-sharing via WeChat, food delivery services are the new norm in big cities like Shanghai and Beijing. The two chief operators are Ele.me and Meituan, and the presence of their delivery drivers is inescapable — you’ll see the former’s blue jackets and the latter’s black-and-yellow flash by on scooters at any hour of the day.

The two have always been essentially indistinguishable, offering the same restaurants for the same prices. But the ground shook last week, for the two delivery apps and for non-delivery apps alike, when Meituan suddenly started offering the ability to call taxis.

Didi gears up for battle against Meituan, now offering the same ride-hailing service.

It’s kind of like if Seamless started offering the same service as Uber. Or to expand the lens, if Instagram unveiled an online marketplace, or if Shazam rolled out a swipe-based dating service. The difference is, while those kinds of leaps probably wouldn’t destabilize too much in the US, Meituan’s sudden move was enough to kick Didi into serious defensive measures.

Back in 2016, government incentives for local companies allowed Didi to force Uber out of the country, leaving the China-owned company with a de-facto monopoly of the space. But Meituan’s recent power play was able to trigger an all-out price war, in which Didi had to drastically drop its prices in order to retain consumer favor.

The move was swiftly followed by an announcement from the country’s biggest travel agency, Ctrip, that it too had been granted a license to offer online ride-hailing services, setting it up to also enter the fray.

So how are apparent newcomers able to enter the scene with such a splash?

Really, it’s just another day in China’s cut-throat, ever-changing, and dynamic economy. The ecosystem is the result of a combination of factors: superpower investors, government subsidies, and a rising middle class, to name just three.

A woman waits for a Didi car beside piles of sharebikes

Superpower investors take huge loads off of consumer wallets in order to win the loyalty of their users. Government subsidies arm companies to do battle with foreign competition (or, to reward major players whose cooperation Beijing deems useful). A rising middle class means more and more people looking to spend their disposable income — but consumers aren’t dumb, and can quickly sniff out which brands are worth their patronage.

It usually ends up one of two ways: with a single entity completely dominating its market (i.e. WeChat in mobile social media or Taobao in e-commerce), or with two near-identical competitors banging it out to win over the customer base (like Meituan and Ele.me).

Nicholas Krapels, a finance professor at East China Normal University and the University of Dayton China Institute, thinks the price-gouging competition is inevitable.

“From a macroeconomic perspective, Chinese consumers, and the drivers on these ride-hailing platforms, are extremely price-conscious. Without any product differentiation between Didi and Meituan’s service, naturally people are going to choose the cheaper option, especially since they already recognize Meituan as a known and respected brand.”

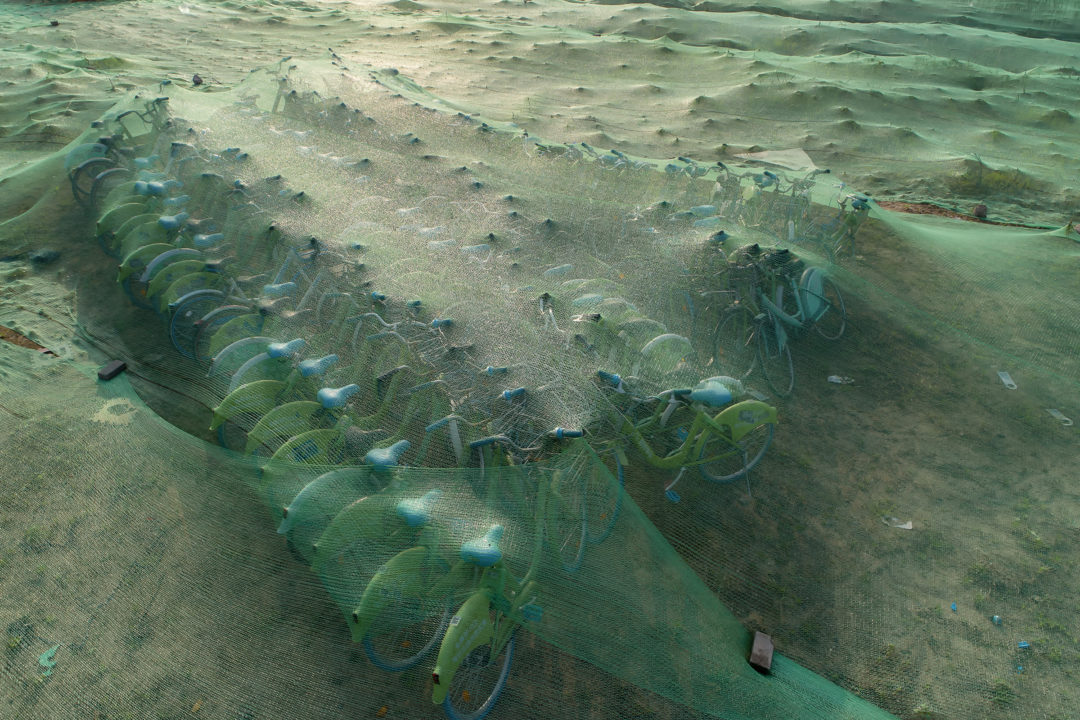

Another example of near-identical brand warfare springs to mind: the ongoing shared bike battle being waged between Ofo and Mobike. Really, there is nothing to distinguish either from its competitor — both bikes inhabit every street corner in China’s major cities, both are scannable through their corresponding apps, and both allow you to ride away for the same price. The only major difference is that one is yellow and one is orange.

![]() Bike-Sharing Behemoths: The Familiar Business Models of Ofo and MobikeArticle May 27, 2017

Bike-Sharing Behemoths: The Familiar Business Models of Ofo and MobikeArticle May 27, 2017

In these kinds of situations, the winner might likely be determined by highly subjective factors. Audience perception that Ofo bikes are easier to find, or that Mobikes are of better build quality could be all it takes to sway the balance. For that reason, the investors behind each company are willing to do whatever it takes to make their product more desirable.

Case in point: ever since I started using Ofo six months ago, I haven’t paid a single cent for a ride. A ride on an Ofo bike ostensibly costs 2RMB (about $0.30), but whenever I hop off a bike to lock it up, I’m asked to verify my payment of 0RMB. To top it all off, I’m given a 2RMB coupon for my next ride, which I already know will cost 0RMB again. It’s a kind of blatant gift-giving that companies hope will secure their spot on top.

Knowing this, it’s easy to see why Didi would rush frantically to drop its prices after the arrival of competition from Meituan. But life is never easy, so let’s complicate things further: this past week, Meituan confirmed its acquisition of Mobike.

So Meituan went from being a direct competitor of Ele.me, to being a competitor of Didi, and then a competitor of Ofo. It’s an enormous jump in scope, and one that would likely be difficult to fathom outside of China’s superpower breeding grounds.

Piles of disused Ofos and Mobikes in Shanghai

But, zooming out even further, we begin to see the fundamental nature of things, the base particles that constitute China’s economic universe. Meituan, Didi, and Mobike are all backed by Tencent, the powerhouse company behind WeChat. And if you’ve been reading the news over the past couple of days, you might know that Ele.me has just been bought by Alibaba, the heavyweight behind Taobao and Alipay, and the root source of China’s e-commerce boom. Alibaba Group Holding Ltd is also a leading investor of Ofo.

As Krapels explains, these latest moves are just one manifestation of a specific strategy by both Alibaba and Tencent:

“Tencent uses cross-ownership structures to leverage its capital and buy into startups at the seed stage, eventually taking them over if they see success. This process makes investment in tangential industries much cheaper. Alibaba also uses this strategy of leveraging cross-ownership structures.”

Roald Thomas Munoz, a Senior Research Analyst at Guotai Junan Securities, elaborates on the battle between the two, and points out that ride-hailing isn’t necessarily a new factor.

“This particular round of the proxy-war between Tencent and Alibaba should come as no surprise to deal-watchers; in the last several months, we’ve seen the two giants go toe-to-toe not only in China but abroad in Southeast Asia, investing heavily in ride-hailing startups like Grab and Go-Jek, as well as race to be the first to get widespread adoption of their respective payments platforms in the region. For China’s business and tech ecosystem, having just two major players is a bit of a double-edged sword. Fierce competition and and an aggressive policy towards strategic investments means startups willing to partner up with these domestic leaders will get funding, connections, and a market quickly. But it also means anyone who doesn’t want to play by their rules risks being left behind.”

In an oversimplified view, when discussing China’s wild west economic terrain, everything kind of boils down to Alibaba vs. Tencent. They’re not the only factors, but when we’re talking about the country’s superpower investors, there aren’t any other names that can compare. They also both work in close collaboration with the central government, which allows them certain modalities of function that foreign companies just can’t match.

![]() One China, Two Ecosystems: Alibaba vs TencentArticle Nov 20, 2017

One China, Two Ecosystems: Alibaba vs TencentArticle Nov 20, 2017

So what about the third factor from our short list up above, the rising middle class?

Right now, it seems China’s consumer class is just soaking up the glow from all of this. Outside of clear measurable trends like GDP growth or the creation of new jobs, the all-out battle being waged for every market sector is only benefitting consumers. Companies are rushing to drop prices, or to innovate new services that give them the edge over competitors.

It means that a college student will be able to afford a Didi to her interview, instead of arriving fifteen minutes late on the subway. It means that a hopeful casanova will be able to woo his date with an effortless dinner and bottle of wine from Meituan, while a suited investor thousands of miles away foots a portion of the bill.

When brands, apps, and companies fight tooth and nail for supremacy, the real winners are the people who pay for them.

You might also like:

Tencent Releases New User Stats at Annual Media Summit, Officially Declares Future “Already Here”Article Nov 16, 2017

Tencent Releases New User Stats at Annual Media Summit, Officially Declares Future “Already Here”Article Nov 16, 2017

Here Comes New Retail: How Alibaba Wants to Change the Way We Think about ShoppingArticle Nov 14, 2017

Here Comes New Retail: How Alibaba Wants to Change the Way We Think about ShoppingArticle Nov 14, 2017