In the recent past, China has been known to the West for its Great Wall and its Terracotta Warriors, as a great ancient civilization that gifted the world with revolutionary inventions such as the compass, fireworks, and beautiful silks, that was subsequently torn apart in the early 20th century and closed off. Even when it re-emerged and became a global manufacturing powerhouse, by and large in the Western consciousness the country still remained a land enshrouded in legends and mystery, about which not much is known beyond the Cultural Revolution.

Now, in the 21st century, China is once more truly becoming the author of its own fate. A new technological golden age seems to be dawning, from innovations in AI and 3D printing, to developments in biomedicine and space exploration — both via private investment and State funding. With this new-found confidence, China has also begun to re-connect with its past and create a Chinese version of modernity that it didn’t have the chance to before. And it is doing so in in fascinating ways — sometimes this means reaching back thousands of years, to draw that connection.

In this article, I look at 13 (a lucky number to the Chinese) pieces of new technology that demonstrate in their conception and nomenclature how China is mapping out its gods and traditions in the cyberverse and the stars.

1 Jia Jia

Created by the University of Science and Technology in Hefei, android Jia Jia is equipped with high intelligence as well as the ability to read and respond to signs of emotion. As interviews have shown, she also has a bit of a temperamental personality.

The design of humanoid robots often embodies our ideals of human perfection. Very few places in the world would release an AI assistant in 2017, and present it like a classical maiden. Jia Jia comes with a range of Han Fu (traditional dress of the Han Chinese from around the Tang Dynasty onwards, preceding the Manchu style clothes of the Qing era).

Whether it is down to the popularity of period dramas, or that a modern equivalent is yet to be found, classical beauty appears to remain an ideal in 21st century China.

2 Digital Lishi

Online platforms such as QQ and Taobao are now offering digital hongbao (red envelopes) around Chinese New Year via their apps. This Spring Festival, the Changsha Evening News teamed up with tourist attractions to plant hundreds of virtual hongbao around the city, which consumers could track down and claim using the augmented reality apps on their phones. AliPay and WeChat have enabled customers to plant hongbao in specific locations anywhere in the country for their friends and families, who can then scan and retrieve the money on their end.

Some things rarely change. Different technologies, same customs. The hongfengbao, popularly known as hongbao, or lishi (an older term used by the southern Chinese; ‘laisee‘ in Cantonese), is an old custom of money-gifting in red paper envelopes on felicitous occasions such as births and marriages. There’s even a minor god in the Chinese pantheon, who looks after loose change called Li Shi. The custom is most well-known in its Chinese New Year form, sometimes also adopted by employers to reward their employees.

In fact, the custom’s iconic image — the bright red packets with full-colour or golden nianhua style images — was established during early to mid 20th century thanks to the introduction of mass colour printing and gold foiling. The custom has clearly once again, adapted to new technologies, via software such as apps, AR and Fintech.

Related:

Advanced Red Envelope TechniquesArticle Feb 14, 2018

Advanced Red Envelope TechniquesArticle Feb 14, 2018

3 The Du Kang Gene

In 2011, results of a study by Fudan University scientists were published pertaining the discovery of an “alcohol-resistant” gene in ancient East-Asians linked to the early development of agriculture in Asian civilizations. Researchers dedicated this gene to Du Kang, the Chinese god of wine.

The earliest legends of Du Kang date back to the Xia Dynasty (c. 2070-1600 BCE), and evolved through the ages as the embodiment of his spirit migrated from a quartermaster to political leader to village winemaker, weaving in mythical elements along the way. Today his name has become synonymous with 酒 (jiu, Chinese for alcohol), and is invoked by companies who want their brands to harness the powerful imagery of this symbol of the great ancient tradition of indigenous wine-making.

4 Shenzhou Spacecraft

The Chinese National Manned Space Programme, or project 921, began in 1968, and was renamed the Shenzhou after its successful test launch in 1999. Shenzhou 5 achieved China’s first human orbital flight in 2003. Since then, the Shenzhou 6 to 11 have successfully completed multiple crewed missions that included the first Chinese spacewalk, first female taikonaut sent into space, and several dockings with the Tiangong space labs (see below). The Shenzhou 12 is currently preparing further upgrades to enhance China’s capabilities in manned space missions to the Moon and Mars.

神舟, Shenzhou, meaning divine ark, is a homonym to 神州, the mystic land, or the land of the gods, an archaic term used to refer to the land inhabited by the Han Chinese people. In mythology, it is the land ruled over by the legendary emperor Huang Di, after he united the tribes. Even today, “Shenzhou” is widely used in the media, arts and education as an instantly recognizable term to the Chinese that evokes the land of their illustrious civilization.

5 Mozi Satellite

The world’s first quantum communications satellite, the Quantum Experiments at Space Scale (QUESS), developed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences in partnership with Austria (IQOQI Vienna), was launched in 2016. Said to be the world’s first hack-proof satellite, it aims to provide quantum communications between Earth and space.

This satellite is also known as the Micius or Mozi Satellite. Mo Zi was a scientist and philosopher born in 470 BCE, who wrote about logic, geometry, and mechanics as well as basic concepts of linear optics in his famous classic, the Mo Jing, or Classic of Mo Zi. The naming of the satellite after Mo Zi is a fitting tribute to the forerunner of the study of optics in China, which eventually lead to the development of quantum optics and to the building of this satellite.

Related:

China Holds World’s First Quantum Video CallArticle Oct 03, 2017

China Holds World’s First Quantum Video CallArticle Oct 03, 2017

6 Xue Long

Designed by the China State Shipbuilding Corporation and Finland-based Aker Arctic Technology, the icebreaker Xue Long 2 is scheduled to be completed in 2019 and to join the Xue Long 1 on scientific research missions and the supply of resources to the polar regions. Together they will be the world’s first icebreakers to go on polar explorations using a two-way ice-breaking technology.

雪龙, Xue Long, means Snow Dragon. China isn’t the only country with dragon totems, but no other civilization has been so closely associated with this mythical creature. What makes long, the Chinese dragon, distinctive from Western dragons is that it symbolizes wisdom, power and good fortune. Like the long, which is made up of many parts (the features of nine animals), the Xue Long 2 is made up of 11 giant sections, to be assembled into one. And like the mythical dragon, it can soar in its element, breaking ice of up to 1.5m thick, functioning at -30C temperatures, and quickly changing direction in ice.

7 Tiangong Space Station

Launched in 2011, the Tiangong-1 is a single module space laboratory and station run by the China National Space Administration with the primary goal of practicing spacecraft dockings to prepare for future explorations of the solar system. Tiangong-2 launched in 2016. Between them they have completed multiple docking missions with various models of the Shenzhou and Tianzhou-1, a cargo and refuelling spacecraft. Tiangong-1’s data has also helped in China’s mineral discoveries, forest and ocean monitoring, and flood control.

天宫, Tian Gong, means Heavenly Palace, which the ancient Chinese imagined were celestial abodes of the immortals. Today, even though stark constructions of assembled circuitry, computers and titanium alloys are sent into space, the Chinese still attach to them the same sense of awe; taikonauts such as Yang Liwei and Liu Yang are immortalized in civilizational history by their journeys to the skies and their sojourn in the celestial experimental module of these bionic heavenly palaces.

Related:

You Can Livestream the Last Moments of China’s Out of Control Space StationArticle Mar 28, 2018

You Can Livestream the Last Moments of China’s Out of Control Space StationArticle Mar 28, 2018

8 Lunar Chang’E Probe and YuTu Rover

After a thirty-year delay, China finally launched CLEP, its lunar space programme, in 2007. Its series of three probes have so far completed 3D mapping of the entire lunar surface, Earth-moon transfer orbit, and first lunar soft-landing since 1976, completing a patrol survey and successful return. The rover that landed with the third probe in 2013, stayed in operation for a record-breaking length of time. This year, the fourth probe is set to carry out the previously unprecedented mission of exploring the far side of the moon.

Due to China’s peculiar history, its people did not live through the first moon landing in 1969 with the joy and anticipation that the rest of the world shared. For centuries however, the Chinese have gazed up at the celestial orb and imagined spirits living there. The oldest of these being a toad and a rabbit; and the most famous is Chang’E, Lady of the Moon, whose image, along with that of the Jade Rabbit, still fill the media and adorn cakes on China’s harvest festival (Mid-Autumn Festival) every year.

Chang’E was once a goddess banished to earth with her husband Hou Yi, the legendary archer. She ascended the moon, after swallowing the elixirs of immortality granted to them by Xi Wang Mu, the Supreme Goddess. Different eras in history have woven in conflicting strands of the Chang’E myth, but she lives on in the Chinese psyche as a symbol of human endeavours to reach for the skies, a spirit encapsulated in China’s naming of its lunar probes the Chang’E. The probe’s rover could have no other name than YuTu (Jade Rabbit), Chang’E’s faithful companion.

In fact, just at the end of last month, China launched the Queqiao, a relay satellite to prepare for the moon expedition of Chang’E 4. The Queqiao, 鹊桥 or Magpie Bridge, draws from another myth, one of the four great legends of China, that of Niu Lang and Zhi Nü, the Cowherd and the Weaver. It’s the tale of forbidden love between goddess and mortal, and sympathetic magpies building a bridge across the galaxy for the star-crossed lovers to meet on the one day of year they are permitted to.

The tradition of celebrating Qi Xi, 七夕, or the 7th day of the 7th month in the lunar calendar, has been revived in recent years as the “Chinese Valentine’s Day”, with many choosing to wed in traditional style. The day is also celebrated as Qi Qiao, the Festival of Skills, in honour of the goddess’ trade on earth, with many cosplayers donning their traditional style costumes. We wish the Queqiao satellite a successful rendezvous with Chang’E 4.

10 BIT Nezha

In April this year, at the Shanghai International Technology Expo, the Beijing Institute of Technology (BIT) unveiled a new robot developed by its Department of Automation: Nezha. Each of the four legs of the pod-shaped robot is made up of 6 electric cylinders, with a wheel attached to the bottom. All 24 cylinders and the wheels work in coordination with the Nezha’s GPS, environmental censors, laser radar, and navigation systems to ensure that the robot can move steadily, with speed and accuracy, while carrying very heavy loads.

The naming of this robot after the child god Ne Zha, is an allusion to his signature weapon, the Wind Fire Wheels. Ne Zha entered Chinese culture around the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) via Buddhism and evolved his distinct identity as an immortal sent from heaven to protect the human world against the surge of demons. His earthly existence is brief and violent, but he transforms into a powerful guardian of heaven when he attains his immortal form.

The protector spirit of Ne Zha certainly seems to manifest itself in the BIT robot. Like the deity it is small but mighty, and its foreseeable uses are not only in the military sphere but also in social care for the disabled and disaster relief — all in all, the protection of humanity.

10 Feng Huo Lun (Hoverboards)

The self-balancing, two-wheel electric scooters, also known as hoverboards, were originally invented by Chinese-American entrepreneur and founder of Inventist in Washington, Shane Chen, and branded the Hovertrax. The factories of Shenzhen emulated this design, quickly producing hundreds of similar products in many sizes and styles. After a couple of celebrity posts about them on social media went viral, hoverboards became the must-have gadget of Christmas 2015.

Their illegality on the roads and pavements of Britain and other European countries hasn’t reduced their popularity in youth culture. The pirated nature of this gadget, which can only be purchased online or at sketchy-looking stalls, has lent it an edgy image, emphasized by its nickname in Chinese. Rather than 滑板 “huaban” (gliding board) or 电动平衡车 “diandong pingheng che” (electronic balancing vehicle), it’s better known as the 风火轮 “fenghuolun“, Wind Fire Wheels, tapping into an alternate version of the child god Ne Zha that has evolved from his presentation in video games.

Although he’s thousands of years old, the nihilistic nature and hot-headed fierceness of this deity makes him eternally relevant to unruly, punky youths.

Related:

5 Most Radical Lithium-Battery Rides on TaobaoArticle Jun 13, 2017

5 Most Radical Lithium-Battery Rides on TaobaoArticle Jun 13, 2017

11 Jiaolong Nuclear-Powered Mobile Deep-Sea Station

A Chinese company is developing this for the China Ship Scientific Research Centre. Set to be launched in 2030, the 60-metre long craft, weighing 2,600 tonnes, will be manned by 33 crew members and powered by a nuclear reactor, with a mission to mine for precious metals and oil.

The current test model of this colossal deep-sea construction is named after the Jiao Long, a mythical water beast with the blood of a dragon, described in historical texts as having four claws, the head of a horse, scales, whiskers and horns. Soaring through both the oceans and the skies, it controls the wind and rain and can change size at will. I hope the Jiao Long test model will prove as agile as the creature from which it takes its name, and hold up well against the turbulent maritime weather.

12 “Monkey King” Dark Matter Detector

In 2015, China launched its first space observatory, the Dark Matter Particle Explorer (DAMPE), to help find the origins of dark matter, which could make up five-sixths of all the matter in the universe. Capable of measuring up to 2 trillion electron volts of energy, the DAMPE is designed to detect cosmic rays and gamma rays (which dark matter is believed to break down into), and to shed light on their source.

The DAMPE is nicknamed the Wukong Satellite, after Sun Wukong, the powerful monkey spirit, also known as the Monkey King, from the 16thcentury classic Journey to the West. Wukong is the name given to the Monkey King by his Daoist master, meaning “to understand the void”. Even in China’s space age, the country still calls upon on this timeless protector and guiding spirit to help it gain an understanding of the unknown — and fill the void in humanity’s knowledge.

The Monkey King is famous for having sight beyond sight, eyes that allow him to see the true form of any of the hundreds of demons he takes on in order to protect his master on their quest for the holy scriptures. Centuries later, his spirit is now guiding the Chinese to dark matter in its true form.

13 Wenchang Space Launch Centre

With its inaugural launch of the CZ-7 Rocket in 2016, the WSLC in Hainan is set to gradually replace Xichang Satellite Launch Centre as China’s 21st century portal to space, supporting spacecraft launches, spacestation operations, and commercial telecommunication satellites, as well as deep space missions to the Moon and Mars.

The launch centre is named after Lord Wenchang, the Chinese god of scholarly success, whose life, interestingly, also began in the stars. The Wenchang Stars is the name given by the ancient Chinese to a constellation adjacent to the North Star. Veneration of this deity developed through the centuries from local earth god worship, to eventually become nationwide, gaining endorsement even from the emperor himself.

Today, temples still fill with offerings from students of all ages and anyone wishing to succeed in the world, with a range of services and merchandise supporting several other industries. The huge abundance of faith across China in Lord Wenchang has propelled this mammoth deity into the 21st century, to watch over scientists and explorers, the scholars of space, on their most challenging endeavours.

—

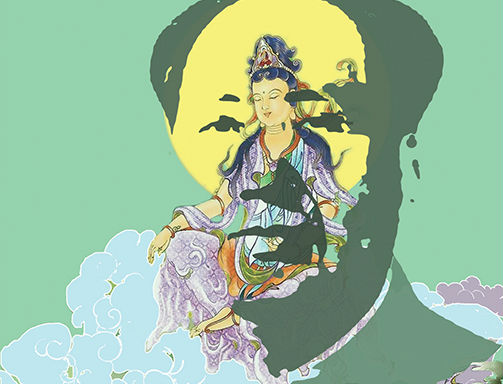

You can read more about Li Shi, Du Kang, the Chinese dragon, Chinese moon spirits, Ne Zha, The Monkey King and Wenchang in Xueting Christine Ni’s new book From Kuan Yin to Chairman Mao: The Essential Guide to Chinese Deities, out now and available in paperback and e-book formats from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and IndieBound.

You might also like:

Author Xueting Christine Ni Explains the Culture Behind China’s Crowded PantheonArticle May 30, 2018

Author Xueting Christine Ni Explains the Culture Behind China’s Crowded PantheonArticle May 30, 2018