Xiaomi is set to launch one of the most anticipated IPOs of the year in Hong Kong within the next few weeks, with numerous sources touting an expected valuation of $100 billion USD that would make it the biggest first-time listing anywhere in the world since 2014.

Despite how it’s often depicted, the brand is now way more than just an Apple “rip-off”, and way more than just an electronics manufacturer. But it’s certainly had its ups and downs in recent years and many remain dubious over such a high valuation.

As Xiaomi readies its IPO, here’s some background on one of China’s biggest tech companies.

WHAT IS IT?

Beijing-headquartered Xiaomi (小米, “little rice” or “millet”) was founded by “serial entrepreneur” Lei Jun in the spring of 2010. The company developed an Android-adapted firmware MIUI that summer and released its first physical product — the Mi 1 smartphone — just over a year later. In 2014 the Mi Pad tablet was unveiled, followed by the first of Xiaomi’s laptops — the Mi Notebook Air — two years after that.

Lei’s founding mission was supposedly that, “high-quality technology doesn’t need to cost a fortune”, and Xiaomi has built itself a reputation for offering impressive specs on its products at low prices, thanks to often wafer-thin per unit profit margins and a largely online-focused sales and distribution model.

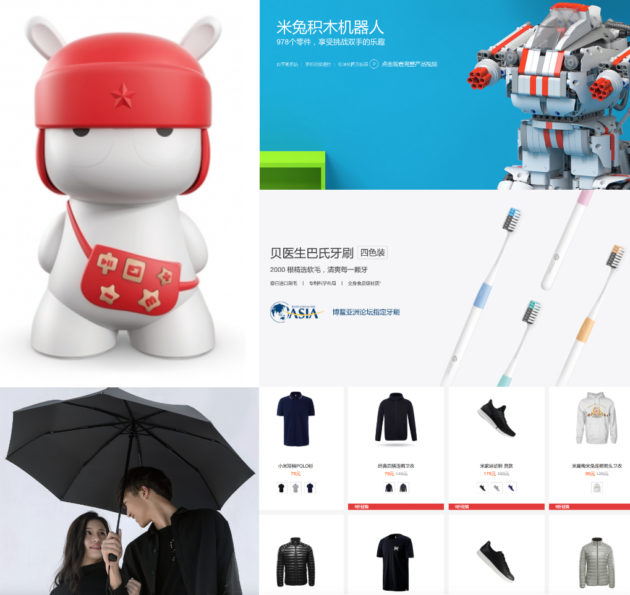

Phones, computers, and their operating systems remain at the heart of the brand, but Xiaomi’s website now offers up a huge array of products. Suitcases, scooters, sunglasses, pollution masks, T-shirts, air purifiers, lightweight SLR cameras, power banks, furniture, the official toothbrush for the Boao Forum for Asia — Mi.com sells all of these, and crucially does so at the affordable prices and with the quick delivery that consumers love.

Lesser-known Xiaomi products (source: mi.com)

As with its phone and other electronics, these products are often released by Xiaomi as part of “limited edition” runs, and can sometimes sell out just through pre-orders. Some spin-offs are more successful than others. The Amazfit BIP, a Fitbit-like band produced by Huami (a related but separate company focused on wearables) has proven wildly popular for example.

Many of these products come with smart elements that enable customers to link them into their other Xiaomi devices. Bought a mini Xiaomi action camera? That’s largely operated through an app on your Xiaomi phone. Admittedly, the items are often compatible with other brands’ phones and computers and not everything Xiaomi sells links up (that’s not a “smart umbrella” pictured above, just an umbrella), but the overall idea is to create an interconnected ecosystem of products, a Xiaomi-branded Internet of Things as it were.

Partly for this reason — despite the plethora of product diversifications — it’s smartphones that remain at the heart of the Xiaomi operation.

These are all the products we launched today in Shenzhen.

Mi 8

Mi 8 Explorer Edition

Mi 8 SE

Mi TV 4 75’’

Mi VR Standalone

Mi Band 3Do you want to take all of them back home with you..? pic.twitter.com/NnOfVEK8og

— Xiaomi #MiMIXAlpha (@Xiaomi) May 31, 2018

AN APPLE COPYCAT?

For much of its life, Xiaomi has been seen as an Apple knock-off. Even founder Lei Jun himself was referred to as a “fake Steve Jobs” in some quarters. Lei apparently took to wearing black turtleneck sweaters after reading a book about the American tech developer in college, though he’s since eschewed such comparisons.

Most of Xiaomi’s early phone, computer, and OS launches were decried as blatant rip-offs by large sections of the tech media, with the products featuring many of the same specs and looks as Apple’s alternatives, just at vastly reduced prices. Here’s one of Gizmodo‘s old takes:

Apple employees themselves weighed in, with the company’s then design head honcho Jony Ive accusing Xiaomi of “theft” and “being lazy” in 2014. Xiaomi’s response? They offered Ive a free Mi phone and suggested he try out their products before slating them (showing that Chinese companies, so often seen as humorless, are capable of a cheeky PR move now and then).

Lei in particular seemed unperturbed; on occasion the Chinese company’s CEO would directly compare Xiaomi’s newly-developed features to those of Apple during showpiece product launches.

Lei Jun (Photo: zhangjin_net / Shutterstock.com)

The “knock-off/cut-price Apple” connotations were so strong that when Xiaomi launched a more original smartphone model in early 2015, the fact it didn’t appear to copy a Cupertino conceived product caused The Verge to run the apparently surprised headline: “Xiaomi’s iPhone 6 Plus competitor doesn’t rip off Apple”.

That proved to be the start of an attempted repositioning from Xiaomi, and in recent years the brand has increasingly tried to move away from the knock-off image of old and establish itself as an innovator.

The repositioning hasn’t always gone smoothly however.

A MI WOBBLE

In 2014, Xiaomi was (for a moment at least) China’s biggest smartphone producer and huge figures began being mentioned in relation to the company’s valuation — including, funnily enough, that of “$100 billion” by investor Yuri Milner. Yet just two years later, such bullish optimism appeared wildly misplaced. After years of sky-rocketing sales figures, Xiaomi’s growth became sluggish toward the end of 2015, before the brand suffered a fall in sales during 2016.

Prospects weren’t helped by an increased investment in R&D (partly to try and shake off the “Apple copycat” tag) narrowing the company’s already very narrow profit margins on its phones (margins it has committed to keeping below 5%), while commentators pointed to Xiaomi’s eyeing up of overseas markets as cause for it ceding ground to domestic competitors.

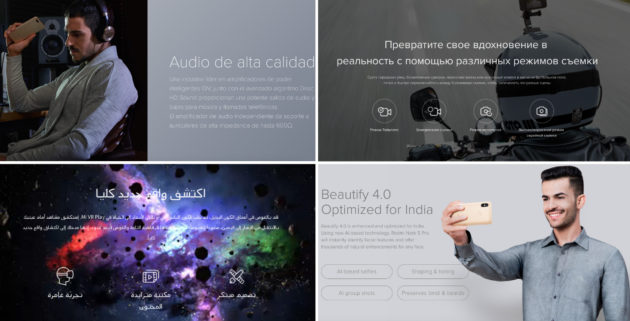

Xiaomi has targeted international markets in recent years

In early 2017, there was more bad news when key executive Hugo Barra quit the firm. Barra had been “poached” from Google in 2013 in a move that was seen as a strong declaration of intent from the Chinese company. His return to Silicon Valley was treated with equal significance however, and (though Barra emphasized personal reasons for the move) the connotations for Xiaomi were far from positive.

WIRED captured the mood in an early 2017 piece that argued “all is not well at Xiaomi”:

Xiaomi tried to grow too big, too fast and now the Chinese phone maker has lost one of its most important executives. […] The loss of Barra will be keenly felt. He was the international face of the company, poached from Silicon Valley, and oversaw its successful expansion outside of China. Xiaomi briefly became China’s biggest smartphone seller, but the market didn’t stand still and Xiaomi, once the most hyped startup in the world, is facing a more low-key 2017.

But in some ways, the widespread negativity masked the beginnings of Xiaomi’s fightback. In October 2016, the company released what they said was “the world’s first full-screen display phone”, the Mi Mix, with 91% of the phone’s front side given over to pixels (some review sites have pointed out that it’s more like 84% screen coverage). Created in collaboration with renowned designer Philippe Starck, the phone was a new benchmark in Xiaomi’s bid to be seen as an original, design-led company and it had both consumers and tech journalists cooing over more than just the price tag.

In August 2017 the Mi Mix scooped a gold level International Design Excellence Award and a month later was inducted into Helsinki’s Design Museum. Despite some genuine innovations, Xiaomi has still found the “Apple copycat” reputation hard to shake off (with some justification of course), but now it too is witnessing other companies following in its design footsteps, having started a rush for bezel-less phones.

The company, once known for its online-only sales model, has also invested in physical stores, with over 300 of them now operating in China. The minimal spaces where customers can try out the products and talk to chirpy uniformed staff bear a distinct resemblance to a certain other electronics brand’s shops, but the entry into the bricks and mortar world of retail appears to have worked out well for Xiaomi: they claim to be the second most profitable company in the world in terms of revenue per square meter (number one just happens to be Apple incidentally).

They’ve also scaled back some of their international ambitions, in apparent recognition that their previous strategy was, as WIRED called it, “too big, too fast”.

MAKING MILLIONAIRES

That’s not to say that everything is rosy again at Xiaomi. Of course, with a much-touted “$100 billion IPO” on the cards, things are considerably rosier than they were even just 18 months ago. But the “Apple copycat” label still lingers, and while the company’s strategy of holding flash sales and limited pre-order runs for its products helps create huge amounts of hype, it can also combine with the aforementioned narrow profit margins to cause significant supply issues.

Xiaomi’s Mi Mix 2

According to TechRadar, just last month Lei highlighted such issues in relation to India, an overseas market that Xiaomi has continued to focus heavily on:

Everyone tells us why don’t we have a larger forecast from the beginning. But then, what if we can’t sell? We’ll go bankrupt. Because we have such thin profit margins, it wouldn’t cover the extra inventory cost in case we’re not able to sell it. We can withstand some 10-12% of buffer but not more than that.

How Xiaomi deals with these aspects of its business model as it grows and exactly how it chooses to invest the money raised via its IPO will be a source of great interest in the coming months. The company’s filing states that around a third of the funds will be spent on international markets, around another third on R&D, and roughly one more third on its “ecosystem”.

The filing also appears set to make millionaires out of hundreds of its early employees who took stock options during the initial phases of the firm.

Whether Xiaomi is good value for such an astronomical valuation remains a subject of intense debate for newer investors, but Lei Jun is characteristically confident: “We have changed how hundreds of millions of people live,” he says in Xiaomi’s prospectus. “And we will become a part of the lives of billions of people globally in the future.”

You might also like:

A Guide to the Coming Chinese Tech IPOcalypseArticle Mar 14, 2018

A Guide to the Coming Chinese Tech IPOcalypseArticle Mar 14, 2018

How Douyin (TikTok) Became the Most Popular App in the WorldDouyin (TikTok) has weathered repeated controversy to be named as the most downloaded non-game app on Apple’s App Store for the first quarter of 2018Article May 09, 2018

How Douyin (TikTok) Became the Most Popular App in the WorldDouyin (TikTok) has weathered repeated controversy to be named as the most downloaded non-game app on Apple’s App Store for the first quarter of 2018Article May 09, 2018

Made in China 2.0: How Li-Ning Sneakers Went from Beijing Outlets to New York Fashion WeekArticle May 22, 2018

Made in China 2.0: How Li-Ning Sneakers Went from Beijing Outlets to New York Fashion WeekArticle May 22, 2018