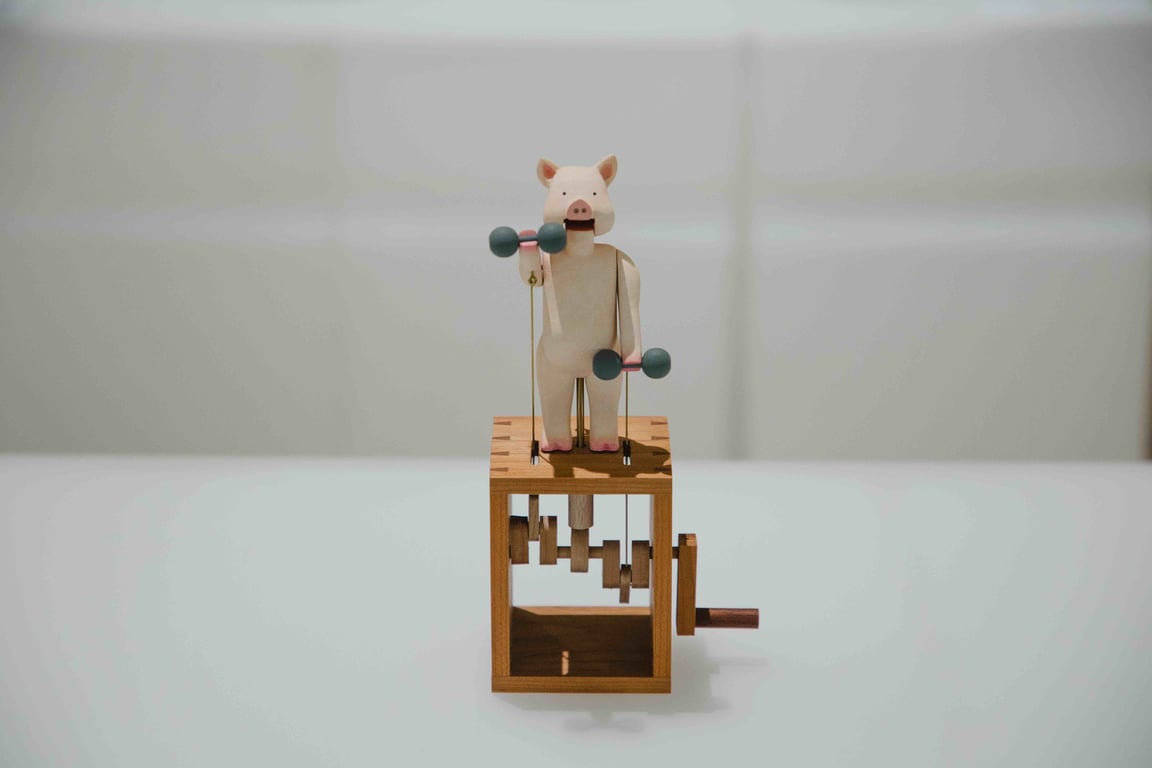

Easily one of the quaintest objects on display at Long Life Design: Thinking and Practice at Shanghai’s Pearl Art Museum (PAM), Kazuaki Harada’s mechanical toy of an anthropomorphic pig may or may not have been inspired by the saying ‘to sweat like a pig.’

Turning a tiny hand crank causes the Yamaguchi-based woodworker’s doll to jump to life and execute bicep curls with tiny dumbbells no bigger than push-pins.

Countless other modern inventions would doubtlessly hold a child’s attention for longer these days. Nevertheless, the battery-free, handcrafted curiosity has a certain je ne sais quoi not found in many plastic playthings that roll off assembly lines.

Objects to Love

Ambitious in scale and subject, Long Life Design: Thinking and Practice encompasses 600 objects and is divided into nine sections, which might sound daunting for any gallery-goer, but take it from us when we say that our visit was one of pure pleasure.

Not a term everyone may have encountered before, ‘long-life design’ was coined by Kenmei Nagaoka, a giant in the field of design. Redolent of the decades-old slow movement of the West, the design principle, which comes with a checklist of requirements, is inextricably intertwined with sustainability. Fundamentally, long-life designs should last for a long time or champion continuity.

During an interview with web magazine Kamado, Nagaoka candidly confessed how much he likes ‘things.’ Nevertheless, the 57-year-old sees room for improvement in our relationship with possessions: “We should treat objects with love and understand the value of those that can endure for a long time.”

The design activist isn’t the only Japanese personality to preach a better appreciation of our belongings: Celebrity and organizing consultant Marie Kondo is also renowned for spreading the gospel of gratitude in our material world. Sweet and sylphlike, the Netflix sensation swoops into the homes of hoarders across the U.S. and helps harried individuals declutter their homes and, by proxy, their lives.

Her famous catchphrase — “Does it spark joy?” — ultimately determines if her clients’ stuff stays or goes and has helped millions choose quality over quantity.

Material World

Ranging from kitchenware (rice buckets, takoyaki pans) to home decor (hand-carved fruit, cork stoppered bottles) and catering to audiences of all ages (artisanal wine for adults, handwoven balls for young’uns), the museum’s wares lie on the opposite side of the spectrum to mass-manufactured goods.

Albeit not uniform, these beacons of slow craftsmanship are more than worthy of appreciation. A tiny kink in stemware wrought of liquid sand, sculptures marked with their makers’ fingerprints, carved fruit displaying the natural undulations of wood — such ‘defects’ lend them a certain charm, and any semblance to perfection is all the more impressive, knowing how they took shape beneath deft fingers.

Life in Plastic

A cheap and convenient material that has circumnavigated the planet, plastic is almost absent from PAM’s exhibition. After all, a basic tenet of long-life design is the use of natural materials.

According to another credo in long-life design, however, one should use existing materials where possible. Hence the water tanks that stand in for seats and pedestals throughout the exhibition; this thoughtful feature serves as a healthy reminder that it isn’t nearly enough to recycle, but that the ‘holy trinity’ of sustainable practices also includes reducing and reusing.

Two new, nifty biodegradable plastic products by Chinese creatives enjoy their share of the spotlight at Long Life Design.

The first of these, Peelsphere, is the fruitful result of textile designer Youyang Song’s tireless search for biodegradable fabric. Together with a team of engineers and designers, Song found a solution in banana and orange peels. Translucent and slightly gummy to the touch, the revolutionary material can be manipulated as one would leather or other synthetic fabrics.

Similarly, plant matter is a central component of product designer Qiyun Deng’s elegant tableware collection called Engraft. Respectively resembling a celery stalk, a pineapple leaf, and an artichoke petal, each fork, knife, and spoon is spun out of polylactic acid (PLC), which is fashioned from fermented corn, cassava, sugarcane or sugar beets.

Unlike plastic, the most omnipresent of materials, biodegradable plastic can be broken down by microbes. Sure, some have decried the latter for misleading consumers, but as that old chestnut goes, choose the lesser of two evils.

Cheap Thrills

China, which saw both economic growth and a rebound in emissions after its first battle with Covid-19 in 2020, might not be synonymous with sustainability. Still, if there’s one thing that Long Life Design: Thinking and Practice proves, it’s that many Chinese makers have their hearts in the right place.

“The concept of long life design is not just in Japan, but also in China,” says Yuki Wang, media and communication manager of PAM, with a sense of pride.

Long-life design is truly inspirational, but for certain audiences, could it be more aspirational than practical? While price points weren’t disclosed in the exhibit, ‘designer’ objects don’t often come cheap. Try telling cash-strapped Chinese youth not to capitulate to the cheap thrills of Taobao when they can barely afford to get wed or bear offspring.

Perhaps real responsibility lies with creators rather than consumers, hence the importance of celebrating makers. In this sense, PAM is on the right track.

Dr. Li Dandan, museum curator and general director of the exhibition, put it ever so eloquently when she said the following: “Thinking about design could go further than [being] concerned only about sales and profit indicators. Design could be a concrete tool and method with humanistic attributes, deeply linking and leveraging multiple fields to make life better.”

‘Long Life Design: Thinking and Practice’ is on view at the Pearl Art Museum (PAM) until November 6, 2022. Allot an hour and a half to comfortably browse the entire exhibition.

All pictures courtesy of PAM