When I first moved to China almost 29 years ago, most people in the U.S. still associated “Chinese culture” with the standard clichés: terracotta warriors, calligraphy, the Great Wall, and maybe KTV if one was being generous.

Fast-forward to 2025 and scroll through any Gen Z’s social media feed, whether they’re in London or Los Angeles, and you’ll probably see a very different China: Labubu blind boxes, Black Myth: Wukong gameplay clips, Haidilao food dances, HeyTea boba hacks, NIO’s advanced EV interiors, and RedNote posts about “county-town aesthetics” or the “bureaucratic chic.” The gap between those two “eras” of China is the space RADII has been documenting for the past decade. From our vantage point as a digital media platform focused on youth culture, we’ve seen five big forces reshaping Chinese culture today—both at home in Asia and abroad.

1. A Tug-of-War Between Statecraft and Street Culture

Chinese culture today is being shaped by two powerful forces:

- Top-down: deliberate statecraft—policy, funding, and ideology—that builds the rails and guardrails for culture, from national policy initiatives to panda diplomacy to state-sponsored media channels. These traditional approaches are designed and shaped by government agencies.

- Bottom-up: a faster, messier surge of scenes—food trends, video games, vinyl toys, street fashion, memes—that travel because they feel native to the internet, not to a ministry document.

Beijing can set agendas and build infrastructure, but it can’t fully script what resonates with a 19-year-old in Guangzhou, let alone in New York or New Delhi. The real story is in the friction between those two dynamics. Policy might set the framework, but young people redraw the picture.

Take Ne Zha 2, which became the highest-grossing animated film ever (2.15 billion USD). Its mix of universal storytelling, high-quality animation, and cultural novelty resonated so strongly because it captured something genuinely emotional about defying fate and challenging the status quo. Or look at Su Chao (苏超), grassroots community soccer leagues that exploded in second- and third-tier cities, where young people organized their own sports culture outside the official athletics system. The state can build stadiums, but it can’t manufacture the energy of a Wednesday-night amateur league.

2. Platforms as Portals: The “Reversal of the Firewall”

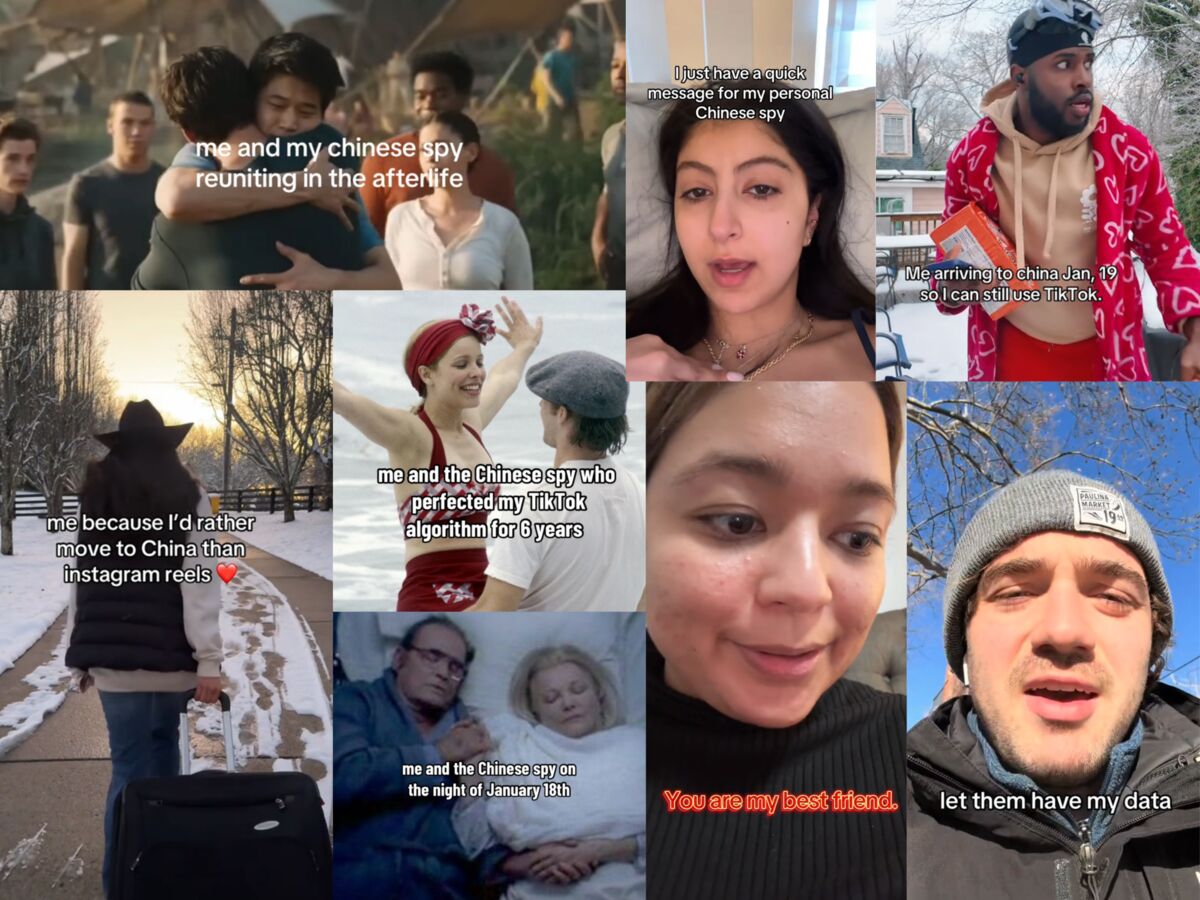

This year’s “TikTok refugees” moment, which saw TikTok users briefly flooding onto China’s RedNote, was a historical glitch in the internet’s direction of travel. For once, Western users were peering into China’s platform space, and not the other way around.

In the past, Western narratives about China were dominated by geopolitics, tension, and suspicion. This year’s “Chinese autumn” signaled a flip, during which U.S. Gen Z suddenly encountered China through vibes, not politics; through subculture, not headlines; through algorithms, not diplomacy. Rather than the typical entry points of mainstream media and diplomatic briefings, it was run-ins with short videos, fashion, toys, memes, and hyper-creative digital subcultures that provided the cultural insights.

These cultural encounters have included:

- RedNote aesthetics like soft-luxury minimalism

- Smooth trap beats from SKAI ISYOURGOD (揽佬)

- Kickboxing matches between humanoid robots

- Addictive two-minute microdramas on ReelShort

- A mad rush for Labubu and Pop Mart collectibles

This phenomenon is what I’d call “algorithmic cosmopolitanism.” In the old model, cosmopolitanism came through elite institutions: study abroad, diplomacy, and global media. In the new model, it’s recommendation engines such as Instagram, TikTok, RedNote, and YouTube that serve you content based not on nationality, but on personal preferences and behavior.

If your swipe pattern says you love street fashion and cute monsters, the algorithm doesn’t care whether that content comes from Paris or Chengdu; you’re going to see guochao looks and blind-box unboxings.

Platforms like these are built on commercial infrastructure. RedNote’s OOTD (Outfit of the Day) economy transformed how fashion brands think about discovery and conversion. Tuanbo (团播), group livestreaming, created entirely new formats where multiple hosts collaborate in real time, turning shopping into participatory entertainment. These are all new economic models being prototyped in China and exported globally.

3. Hybrid Aesthetics and Nostalgia: When the Past Becomes Data

Many people outside China still picture Chinese modernity as a break with the past. On the ground, the opposite is happening: the past is being remixed, not erased.

You see it in the hanfu revival and the broader “Neo Chinese Style” (新中式): streetwear, interiors, and even global brands like adidas’ China-exclusive capsules with Tang-jacket cuts and mandarin collars have hacked into traditional Chinese silhouettes, fabrics, and motifs.

In 2025, adidas went all-in on localization, staging its “POWER OF THREE” fashion show during Shanghai Fashion Week with 100-plus looks that reimagined the three stripes through the lens of “Modern China,” designed by local teams and available for immediate purchase. This is also a perfect example of how a global brand is finally learning to speak in a local accent.

You see similar remixes in Black Myth: Wukong and Ne Zha 2, and you also see it in world-renowned fashion designer Kim Jones joining Bosideng, turning a domestic down-jacket brand into a luxury collaboration worthy of Paris Fashion Week. When global creative directors start validating Chinese brands, the power dynamic shifts; it’s no longer the “China market” but the “China partner.”

This is Lawrence Lek’s Sinofuturism as lived culture: China imagining the future by feeding its own history into the machine. The past becomes data; tradition and identity become innovation.

But there’s another layer: material nostalgia. Vintage shopping exploded in 2025, with young people in China excavating the textures of recent history. Chinese perfume brands emerged, bottling olfactory memories from the past: White Rabbit candy, osmanthus courtyards, green plum wine. Scent became another avenue of reclaiming identity.

Layered onto this is a powerful wave of youth nostalgia. China’s Gen Z is growing up under intense pressure: neijuan (内卷, or “endless competition”), slowing mobility, high youth unemployment, and rising costs in megacities. Nostalgia—’90s and ’00s aesthetics, childhood snacks, old county-town signage—becomes an emotional refuge and a counter-rhythm to the speed and anxiety of contemporary life.

Ironically, these hybrid aesthetics are not exclusive to China, as youth across the globe struggle with the pace and stress of rapid change. This return to nostalgia and tradition as emotional refuge harkens back to the ideas of cultural theorist Mark Fisher’s “lost future.” In a time of economic stagnation, technological acceleration, and cultural exhaustion, young people increasingly turn to nostalgia, retro aesthetics, and cultural remixes as a way to cope with blocked possibilities.

This fusion of high-tech-meets-heritage and luxury-validates-local is what makes contemporary Chinese visuals so intriguing globally.

4. Statecraft as Soft Infrastructure: Exporting Systems, Not Just Stories

When we talk about soft power, people like to compare Hollywood, K-pop, and anime. That’s still relevant, but China is playing an increasingly divergent game.

Instead of only asking, “What story are we telling?” policymakers are asking, “What systems are we building?”

Since 2017, cultural confidence discourse has coincided with policy decisions to promote investment in the infrastructure of culture. Some of those policies were deliberate, such as tourism zones, museum ecosystems, and digital heritage. But other policies, by default, have also become homegrown systems that have won global admiration, like competitive and efficient ecommerce and livestreaming platforms, short-video formats, and even EV ecosystems and AI creation tools.

From Temu and Taobao to ReelShort and Dramabox, from NIO’s UI to Qwen’s AI models, China is exporting not just content but the pipes through which content flows and the tools to create it.

You can think of this as architectural soft power. Instead of persuading you with a narrative, it invites you into a system:

- Buy low-cost, fast goods through a Chinese e-commerce logic

- Watch bite-sized dramas built on Chinese platform formats

- Drive an EV whose interaction design was born in Shanghai or Hefei

BYD and NIO are exporting an entire philosophy of what mobility, connectivity, and domestic space can be. Mixue, now one of the world’s largest fast-food chains, started out selling soft-serve and bubble tea in third- and fourth-tier cities, demonstrating how smaller-city players leverage these commercial rails to claim participation in consumer culture on their own terms: affordable, unapologetic, and scaling up.

Intangible cultural heritage (非遗) followed the same path. Traditional customs and crafts moved from museums to Douyin, productized in viral tutorials and turned into social activities and merch that fund their own preservation. Whether that’s authentic revival or extractive capitalism depends on who’s profiting. In that sense, China’s cultural influence is increasingly contextual. The challenge, and the opportunity, is how to keep those pipes open to grassroots creativity rather than overengineering what flows through them.

5. Culture Under Constraint: Coded Creativity in the Dark Forest

One of the most misunderstood aspects of Chinese youth culture is how much of its originality emerges precisely from constraint. High pressure, censorship, neijuan, and the grind of 996 are not romantic conditions. They create a landscape in which creativity must adapt, disguise itself, and find indirect pathways to expression.

To understand this creative ecosystem, we look to Chinese science fiction writer Liu Cixin’s “Dark Forest.” In Liu’s metaphor, the universe is a dark forest where everyone hides their identity and speaks in oblique signals to avoid drawing attention for fear of being misinterpreted or attacked. Increasingly, Chinese youth treat the internet, and sometimes society itself, the same way.

Online culture becomes:

- Coded rather than explicit

- Symbolic rather than literal

- Playful rather than declarative

- Layered rather than direct

This “Dark Forest” logic gives rise to subcultures built on implication, irony, humor, and visual codes that travel faster than words ever could. Creativity lives in subtext. A few examples:

Ghost Fire Boys (鬼火少年)

In rural provinces, young men modify cheap Yamaha scooters with neon lights and custom exhausts, racing through county streets and filming “street bombing” (“炸街”) runs. On the surface, this is thrill-seeking. Underneath, it is expression in motion—a coded way of reclaiming agency when other pathways to identity or mobility feel blocked.

Tingjufeng (厅局风), or “bureaucratic chic”

Plain shirts, dark trousers, thermos mugs, sensible shoes. This is the uniform of mid-level bureaucrats. On RedNote and Douyin, Gen Z cosplays this aesthetic with winks and smiles. It’s a coded commentary on the desire for stability in an unstable economic landscape. When the future feels unpredictable, dressing like someone with a guaranteed pension becomes its own satire.

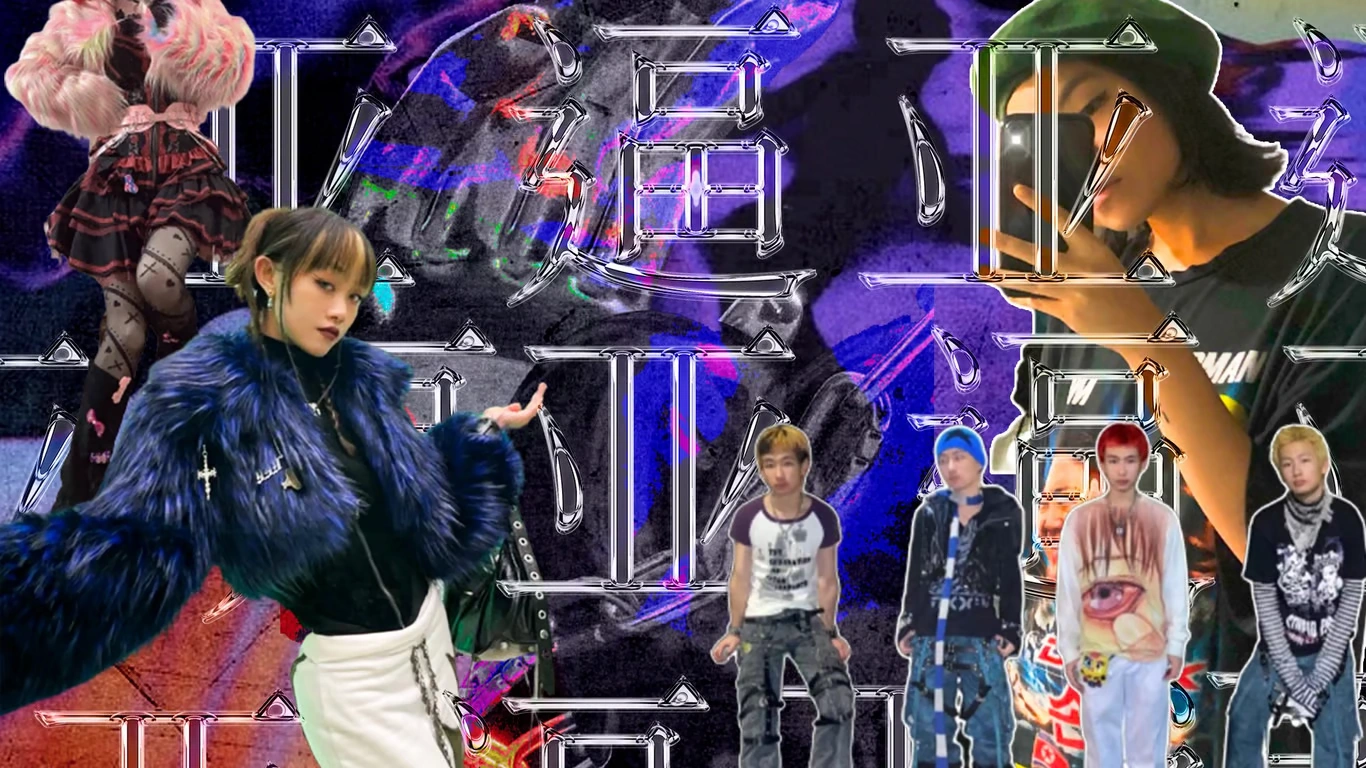

Tucool (土酷)

This Y2K-inspired aesthetic celebrates what was once considered tacky: leopard prints, photo-studio backdrops, gaudy filters, and Qzone graphics. Tucool is both ironic and resistant. By exaggerating “uncoolness,” young people reclaim the right to define taste on their own terms. It’s a Dark Forest tactic: humor as camouflage, kitsch as armor.

County-town style (县城风)

Muted shots of peeling tile floors, ’90s neon signage, plastic stools, stairwells. These are scenes from third- and fourth-tier China. Rather than an aesthetic of poverty tourism it is a visual form of longing, displacement, and subtle critique—a way to memorialize the textures of childhood or vanished towns without ever saying why they vanished. The message is emotional versus explicit.

Yabi (亚逼)

Once an insult, now reclaimed. Yabi fuses punk, hyperpop, rural kitsch, and “rat-people energy” (鼠鼠人). It’s the self-aware humor of those who know they’re not at the top of the system but refuse invisibility. It’s rebellion by remix, agency through aesthetic chaos. In the Dark Forest, absurdity is safer than clarity; eccentricity is a shield.

They are survival strategies disguised as style—ways for young people to communicate feelings that can’t be expressed directly: frustration, hope, irony, resignation, aspiration, and humor.

That is why Chinese youth culture feels so visually inventive, so layered, and so strange to outsiders: it is built for those who know how to read the room, hide meanings in images and jokes, and speak in subtext because subtext is safer.

Remarkably, this coded creativity has become one of China’s most distinctive cultural exports. Global audiences—even without understanding the political or social contexts—feel the energy, the tension, the humor, and the hyper-stylization. They sense the authenticity embedded in the aesthetic encryption.

Where Does This Leave Us?

As someone who has watched China’s transformation from internet cafés to TikTok refugees landing on RedNote, I believe we’re witnessing a convergence of “the state” and “the street,” where the youth have adeptly adapted to a system that contains guardrails but also has provided accelerators to cultural evolution. As a result, the future of Chinese culture will be defined by how well these two forces co-evolve.

The real test is whether the rest of the world is ready to read the signals, decode the subtext, and recognize that the most revealing story of China today is being written far from the headlines.

Cover image via Instagram/@eastermargins.