How do you make a bowl of delicious Song Dynasty pebble soup? Easy. You pick eleven or twelve little white pebbles from a flowing stream — making sure they have moss on them. Then add a scoop of spring water, and simmer until it turns into a broth that tastes “as sweet as escargot” with a hint of spring rain.

This is an actual recipe taken from the pages of Shanjia Qinggong 《山家清供》, the most iconic cookbook of the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE). While the author may have gotten carried away with the occasional dish — at least by modern standards — the book covered a wide range of what were then seen as simple and nutritious recipes. Ingredients were always seasonal, usually grown on the mountains, and prepared in a way that was both minimal and poetic.

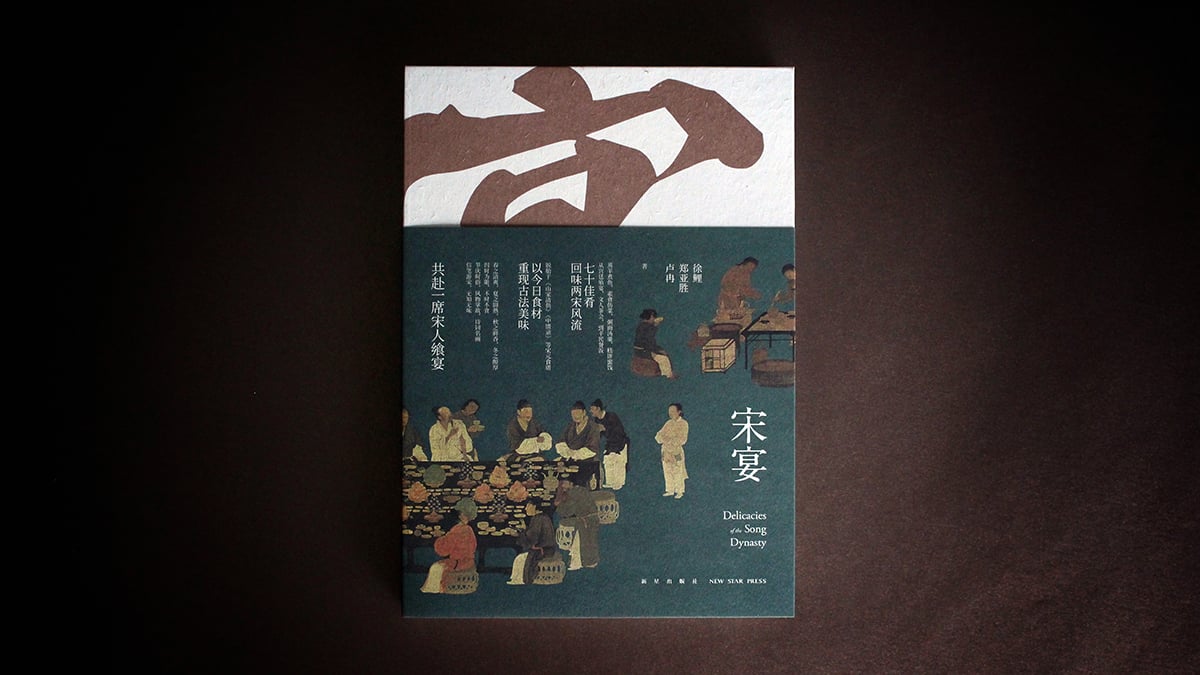

Delicacies of the Song Dynasty

Recipe books like this one gave authors Lu Ran, Xu Li, and Zheng Ya Sheng the idea for Delicacies of the Song Dynasty 《宋宴》, a cookbook that contains 75 beautifully-photographed dishes, as well as vivid documentation of how Song-era people worked, travelled, communicated, and found comfort and pleasure through food.

Song was when Chinese cuisine leveled up in terms of diversity and nutritional value. There are said to be around 1,000 recipes preserved from this era. To produce Delicacies, the three authors conducted extensive research, comparing notes from Song food writers with cookbooks from earlier and later dynasties. They narrowed their selection down to about 150 dishes, and remade each dish multiple times for accuracy. None of them were chefs by training. The project took them five years to complete.

Setting the stage in Hangzhou (formerly Lin’an), China’s capital during the Song Dynasty, the book paints a detailed picture of what ordinary city dwellers, bistro owners, literati and dignitaries’ kitchens all might have looked like.

We learn that pork was for commoners, the imperial court loved sashimi, and the well-educated admired clean, minimal, healthy food. And waimai — ordering delivery — was just as common as it is today.

The emperor was known to consistently order waimai, especially when the aromas of street food reached his nostrils and made him nostalgic.

Related:

In Shanghai, You Can Now Get Take-Out Food Delivered by DroneArticle May 30, 2018

In Shanghai, You Can Now Get Take-Out Food Delivered by DroneArticle May 30, 2018

It’s far from the first time in history that our civilization has prized seasonally-sourced ingredients, either. Song society valued it immensely; it’s where we get the Chinese phrase “bu shi bu shi” (“not seasonal, not good to eat,” 不时不食).

“They did try to grow food off-season, but were restricted by the technology of their time, says author Lu Ran. “[Because of this] they were compelled to eat according to the season, which I think is a very healthy and natural way of living,” says Lu. “It was also when ingredients reached their peak quality.”

Related:

Meicai: The 7 Billion USD App That Wants to Change How China EatsArticle Nov 12, 2018

Meicai: The 7 Billion USD App That Wants to Change How China EatsArticle Nov 12, 2018

One of author Xu Li’s favorite recipes is plum cake soup (梅花汤饼 meihua tangbing). What could have easily been a simple dough soup in chicken broth was then infused with plum and sandalwood water to create a subtle aroma, with dough sliced into the shape of plum flowers. This reflected how much litterateurs of the day adored and appreciated white plums.

Plum cake soup (梅花汤饼)

Song Dynasty dishes like hairy crab-stuffed orange (蟹酿橙 xie niang cheng) are surprisingly close to what modern Chinese people are eating today. “We still share a lot of common ingredients with the everyday Song household,” says Lu. Though some variations still hold based on the tastes of the time, such as Song chefs pairing hairy crab with citrus rather than vinegar.

Hairy crab-stuffed orange (蟹酿橙)

Song recipes tended to also rely on creative solutions for a better dining experience. Mock meat dishes — not to be confused with meat substitutes often eaten by vegetarian Buddhists — were one method through which Song Dynasty chefs could recreate the flavors and textures of otherwise unobtainable ingredients.

They would often prepare sliced mandarin fish as “fake clams,” or diced pork belly as a substitute for much pricier scallops. They even attempted to recreate the egg of a dapeng (大鹏) — a giant bird in Chinese mythology — by placing egg yolk and egg white respectively in a pig’s and sheep’s bladder and steaming them together. The team says that they were often amazed by how gifted their ancestors were.

Published last August, Delicacies of the Song Dynasty is already in its third printing. “We realized through creating the book that most Song people were really just living the way we are living now,” says Xu. The authors hope to publish an English edition soon, and plan to tackle Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE) food as their next project.

In the end, what matters most to these three authors is giving readers something a museum cannot offer — reliving history in their kitchens and through their tastebuds.

Delicacies of the Song Dynasty is currently available for purchase on Douban.

Header image: “Fake clams” (鯚鱼假蛤蜊) made from less expensive mandarin fish