“If we wanted a picture of the future, we should imagine a boot stamping on a human face,” wrote George Orwell in the dystopian science fiction novel 1984. If Orwell was still around today, he might have used different imagery — such as a giant screen crushing a tiny human.

Some might say that we’re already living in a tech-dystopia dominated by screens of all shapes and sizes. From our ever-expanding phones to the enormous 3D ads that seem to leap out of billboards, screens constantly affect our optic nerves from every angle and vie for our attention. It’s hard to think of any other object that’s as ubiquitous in our daily lives.

No one is more aware of this than contemporary artist Ding Shiwei. Screens are both a primary medium and the underlying subject of the Hangzhou-based creative’s art.

Ding works with several hardware suppliers — most of whom he discovered via Taobao — to source state-of-the-art technology and remarkable screens you didn’t even know existed. His unusual materials find their way into video installations that are simultaneously amusing and downright disturbing. Most of these installations were presented to the public for the first time during the solo show Faith on Tap at Gallery Vacancy in Shanghai.

Do ever-present screens alter our perception of reality, information, politics, religion, and freedom? Ding certainly thinks so, and hopes to make the public see his point of view. His art, which paints a grim prophetic picture of the future, will make you reconsider your screen time.

The global pandemic, as well as events close to home, have emphasized technology’s role as a double-edged sword.

“Today, we have more access to essential information and data than ever. This brings possibilities, but it also causes problems,” says Ding, before addressing China’s Covid-19 health code system, which doesn’t just know who you’ve come in close contact with but also collects personal information, such as commuting data and health status.

“There is no doubt this [the system] helps control the virus, but its color code decides your degree of freedom. It’s like a giant, invisible hand dividing society through a health code. This has serious political implications,” says the artist somberly.

This connection between screens and politics is evident in The Jokers’ Revolution No. 1, a reinterpretation of American artist Annette Lemieux’s iconic 1995 work titled Left Right Left Right. The original installation sees black and white photographs of raised fists belonging to famous icons like Martin Luther King, Richard Nixon, and Jane Fonda plastered on the kind of signboards typically carried by demonstrators.

Ding’s 2020 version also depicts raised fists on signboards, except with a slew of different — albeit equally noteworthy — personalities; think famous cartoon characters like Mickey Mouse, Homer Simpson, and Bugs Bunny, all in bright colors.

“When compared with Annette Lemieux’s piece, my work completes a cross-temporal echo through which we can see how the medium of the screen has influenced human participation in political life over the past two or three decades,” Ding says. The flat blue hue in the background of The Jokers’ Revolution represents the internet and hints at how social media has become the new public square for political manifestations.

Ding’s cast of cartoon characters isn’t random, but carefully considered. According to the artist, partaking in politics is something of a performance these days — especially when it happens on social media.

“Today’s internet users are dimensionally reduced. They hide behind their screen to express their opinions. Even taking part in politics has become something highly performative,” he says, adding that social media users strive to “create a perfect, enviable, and highly recognizable character.”

Raised fists are a recurrent theme in his work. He’s drawn to how they can have different meanings, like functioning as an emblem of unity for the historical Black Power movement in the United States. More often than not, a raised fist symbolizes the spirit of revolution and is regularly seen as such on social media.

In some of his pieces, Ding reclaims the raised fist emoji by rendering it in different ways, from incorporating different skin tones to inserting easily recognizable symbols, such as a Tom & Jerry-esque mouse hole or a crystal ball.

“I’ve always been interested in symbols, and I love digging into the politics behind them,” he says.

Recently, he has developed a fascination with the appearance of symbols in delightful and glossy forms on the internet, such as emojis. He finds the association between ‘cute’ and ‘political’ content intriguing — and potentially deceiving.

Ding’s Aesthetic Distance series serves as a prime example of lighthearted artworks with dark undertones.

In Aesthetic Distance No. 4, a round screen outfitted with a sensor depicts a smiley face emoji, which eerily collapses in on itself when anyone comes within a meter of it. Similarly, approaching Aesthetic Distance No. 2 will cause the ‘undoing’ of Disney’s longtime mascot Mickey Mouse.

“These works allude to the changes brought on by the pandemic, related to social distancing measures,” explains Ding. As we all know, authorities the world over have recommended keeping a physical distance of at least one meter from others.

“I chose the emoji and Mickey Mouse because their images have strong anthropomorphic characteristics and are instantly recognizable. The interaction between an actual human and these digital avatars also creates another layer of reverie,” says the artist, who enjoys inspiring interactions with his installations.

Ding is also drawn to simple, straightforward, and smart ideas that, with a bit of technical knowledge, have the means to establish tension between audiences and artworks.

The Spinning Wheel of Death serves as an excellent example of this. Ding recreated — or more like ‘wrecked’ — one of Gallery Vacancy’s concrete pillars for this site-specific work. Surrounded by rubble and split in the center, the pillar is paired with a levitating UV-printed model of the spinning pinwheel used in Apple’s macOS. Also dubbed ‘The Death Wheel,’ the dreaded symbol, which many have come to associate with a tedious wait or a computer malfunction, has millions of searches on Google (presumably by macOS users looking for a quick fix).

The striking work of art is infused with visual and physical (magnetic) tension.

Ding says, “The boundary between the virtual and real worlds is becoming increasingly blurred. Everything in the real world is now affected by the power of the virtual world. This work hopes to provide a Luddite-style reflection of whether these changes are pushing human beings into an irreversible abyss.”

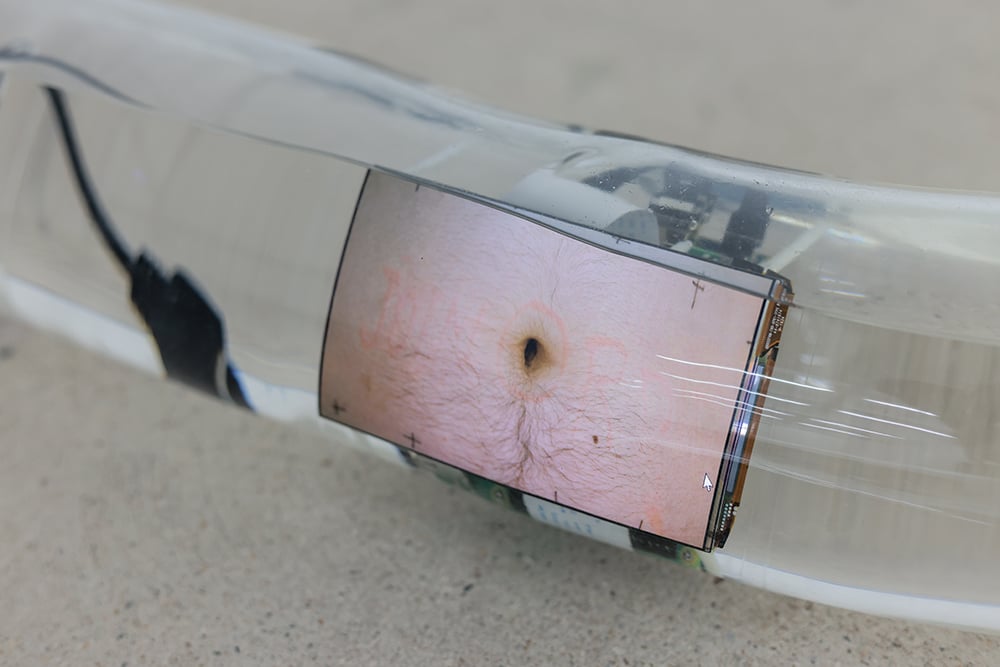

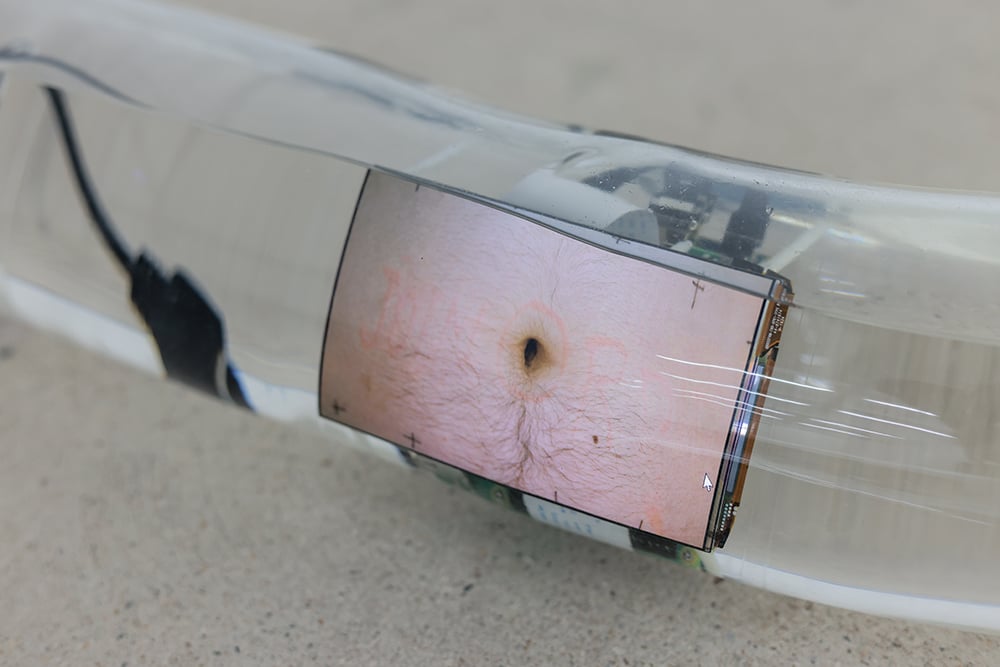

Things get even more dystopian with The Vanishing Prophecy No. 3. To create the video installation, Ding planted small screens inside several acrylic tubes filled with a formaldehyde-like liquid. Unaffected by the liquid, the screens displayed close-ups of human skin scratched with messages from tech slogans, protest chants, and religious texts.

“These slogans tell us how today’s screen society is intervening in our lives, reality, and even our bodies,” Ding says. He then describes a vision of a post-apocalyptical future where machines have replaced humans, keeping them in similar tubes: “This is the ultimate prophecy about the fate of humanity.”

As usual, an element of tension exists in the artwork by way of juxtaposing liquid and electronics — a feat only made possible by using a rare, colorless transformer oil resembling water, but capable of insulation.

Screen Flag No. 1, another ingenious piece by the artist, is made up of an ultra-thin screen that flutters when blown by a small fan. Redolent of a waving flag, the screen depicts an animated emoji eye against Ding’s usual blue background.

“This piece reminds us of George Orwell’s famous quote, ‘Big Brother is watching you.’ I think the prophecy he describes has been fulfilled, but in a more coveted, camouflaged, and ‘cute’ manner,” warns the artist.

Ding takes the audience’s viewing experience to the extreme in Left-Right Montage, a binocular installation with two microdisplays instead of lenses.

Powered by a microcomputer, each lens depicts a different scene, which completely reveals itself when the viewer is totally immersed. Tapping into man’s voyeuristic instincts, the work also posits the possibility of technology taking over our minds.

Left-Right Montage brings attention to the bewildering effects of computer-generated immersive environments, and the threat of the metaverse — our soon-to-be reality, and a time when screens will swallow us completely.

While we are only just brushing against the fringes of the metaverse, screentime’s hold on our minds is nothing new. Ding notes how, at least since the 1970s, television has been used as a medium for evangelization in many parts of the world. This thought is expressed at the start of his Screen Belief series, which combines four screens of equal size to create an effect similar to Tadao Ando’s cross.

“I wonder if, in the future, the screen itself will become the main body of belief,” he says.

Still, there’s hope — or so the artist’s works imply — that humanity will resist the singularity.

In the installation titled Screen Flag No. 2, a flexible LED screen depicting dystopian slogans resembles a flag — complete with a broken flag pole — that has come tumbling down.

“It is like the rubbles of a revolution,” explains Ding. “Perhaps, the object of the revolution is none other than the screen itself.”

Additional reporting by Lucas Tinoco

All images courtesy of the artist, Imagokinetics Lab Hangzhou, and Gallery Vacancy