Level Up! is a series exploring video games and digital entertainment in China. In this article, we explore how video game artist Xia Han employs technology to denounce the negative consequences of our species’ advancement.

In a time when an A.I. chatbot can compose this paragraph in only a few seconds, it’s hard for some of us not to feel concerned about what lies ahead. Ask Xia Han about the future of humanity, and he’ll say: “In a best-case scenario, a Brave New World. Worse case, The Matrix.” Clearly, Xia doesn’t have a very positive take on everything happening in the tech department, and judging by most of his works, to him, the cyber-dystopia has already begun.

As a multimedia artist and one of the three founders of Shanghai independent art space 33ml Offspace, Xia uses “technology to criticize technology,” as he puts it. With video games, his primary medium, and digital paintings and animations, he explores issues such as how arbitrary technology curbs our freedom, pervades our consumer culture, and dumbs us all down.

“My work is a simulacrum of reality. It starts from personal experiences and events that influence or touch me,” he says. As a fan of magical realism, he likes to create fantastical stories to depict issues, characters, and even historical events.

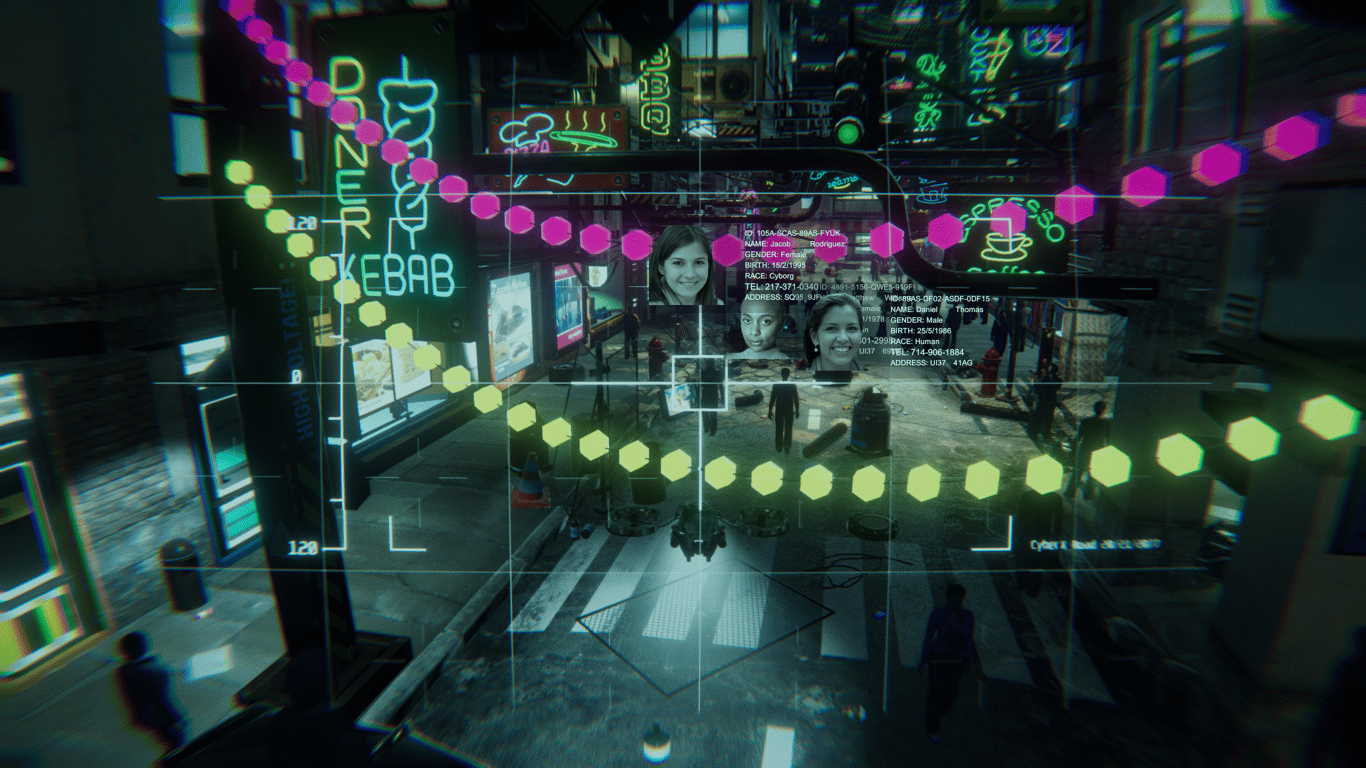

In Xia’s game No Escape, the player controls a drone that watches over the citizens of a city with a high-tech, low-life atmosphere. With this work, the creative explores the concept of ‘surveillance capitalism’ and how our most private experiences become resources for governments and corporations. As the drone hovers over people, we can see their profile pictures and a visual chart with all their personal data.

Xia’s relationship with technology, however, wasn’t always so skeptical. It started on a high note and, unsurprisingly, through video games. Born in 1993, he played on his Game Boy Advance throughout elementary school before switching to PC and PS3 in junior high.

“I might have been one of those boys who were poisoned by video games, as we see nowadays in the newspapers,” he laughs. “I was only 4 when I started gaming, playing pirated versions of Need for Speed, Diablo 2, Counter-Strike, and so on.”

When he visited the futuristic, video-game-like district of Akihabara in Tokyo at age 15, Xia was mind-blown by the CGI he saw on posters and billboards and felt like living there forever.

Xia was also exposed to contemporary art growing up, primarily by visiting Shanghai’s M50, then a burgeoning art district.

“I visited Eastlink often,” he says, referring to the influential gallery that hosted some pretty disruptive shows, including Ai Weiwei’s infamous Fuck Off in 2000. “I couldn’t understand most of the works at the time, and frankly, I didn’t like them very much. The images were gaudy and ugly. That was my biggest impression,” he recalls.

It was at M50 that he stumbled across Feng Mengbo’s pioneering video game art for the first time. Xia remembers a detail in one of Feng’s works where the player could beat up a security guard from the Central Academy of Fine Arts.

Years later, when he went to East China Normal University to study conceptual art, he was majorly disappointed with the curriculum, so he turned to music for inspiration, specifically to the futuristic pretensions of the electronic scene.

“Electronic music became my salvation. Kraftwerk, Yellow Magic, and Daft Punk all entered my vision. The samples in ‘Giorgio by Moroder’ completely shaped some of my thoughts. Giorgio used synthesizers to create the sounds of the future, and I felt that the art environment in China lacked the same excitement,” Xia says.

Prompted to also “look to the future” in his own field, Xia began learning creative coding. His first works looked as basic as a Windows XP screensaver but developed into more elaborate concepts after some time, notably using video game frameworks.

“Video games are very interdisciplinary. They contain story scripts, 2D and 3D art assets, computer programming, music, and a lot more. If you want your game to be fun and engaging, you must also understand game psychology,” he says.

To control every aspect of the universes he creates, Xia works on everything alone, using no less than 20 software programs. He’s drawn to the fact that video games can be easily updated and combined with the internet and hardware to influence how people perceive and interact with the world.

His fixation went beyond games, though.

“I was deeply fascinated with technology and the possibilities of quantifying the human body and the extension of the senses. I studied programming in a makerspace where people were developing products that really helped others, like devices that allow paralyzed artists to control a paintbrush through brain waves and video games that identify children with autism through data collection and give them guidance,” Xia says.

He remembers how a friend explained the concept of “everything is quantifiable” to him, preaching that algorithms could restore the physical world and the laws of truth, which meant that utopia would come when everything on Earth could be digitally simulated and predicted. Tech and humans were a perfect combination, and there were no limits to what they could achieve together. Or so it seemed.

Everything was flipped on its head when Xia came across the theories of Shoshana Zuboff and Byung-Chul Han and the artworks by Hito Steyerl, great modern thinkers who lift the veil of technology to help us see what lies underneath.

“I had to rethink the impact of technology under the power of capital,” he says. Especially when working on No Escape, he became more aware of how Web 2.0, which emphasizes user-generated content, traps its users in ‘information cocoons’ or echo chambers that polarize society and block critical thinking.

“The iteration of A.I. with other digital technologies will only speed up the demise of those who are more vulnerable and give rise to more ‘milk bottle culture,’” Xia says, alluding to the replacement of people’s jobs because of A.I. and the shallow and low-quality nature of the content that dominates social media.

His questioning became more intense when he returned to China after spending a period in London for a master’s degree in fine art at the Chelsea College of Art. He landed when the outbreak of Covid-19 was in full bloom, and the Chinese government employed tech resources to monitor and predict group behavior.

“Government and corporate surveillance on all fronts have made people no longer feel safe but resentful and worried,” he says. “Machine learning is rapidly advancing computer vision recognition, and China has become the largest training ground for the algorithms, which makes surveillance costs dramatically lower. Developers can listen in with impunity and steal users’ private information for commerce.”

Xia explains that he choose video games as a medium because it reflects some of our behavior patterns.

“The rules established by gamified work culture constantly stimulate human reward mechanisms, creating lasting excitement and hiding the essence of capitalist exploitation. Moreover, smart living and gamified marketing are dipping into our lives, not to mention the explosion of virtual economies and communities such as Web 3.0 and the metaverse. I think the concept of video games will be even more pervasive in the future, but I can’t say whether this is good or bad,” he admits.

One thing is for sure, though: Xia is not fond of the metaverse.

“Right now, I’m disgusted by the idea. If this is really the ultimate home of humankind, it can only be a virtual space full of advertisements and cheap entertainment. Besides, the anonymity it enables destroys the relationship of trust between people. There will only be a game of interests, not idealism, and, to me, this world is bad.”

Two specific works are great examples of how Xia himself leverages gamification techniques to ‘reward’ his audience and lead them through his worlds: Animal Farm and Tonight You Won’t be Sorry. Combined, they explore the ideas of power, identity, and truth in media — all in light of the death of Jamal Khashoggi.

In the game universe, the player pilots an investigative journalist on a quest to solve a conspiracy mystery involving a farm, a slaughterhouse, and a chemical plant. The works show a high level of animation quality and detail. Xia infuses his non-interactive segments with cinematic quality, exploring different camera angles and soundtracks to build up the narrative, which ends grimly — not too different from Khashoggi’s plight.

“The virtual world is a way to transpose my worldviews into fiction,” Xia says. “Of course, it also helps to avoid censorship. I like to create prophetic stories, and when I was organizing some of my works, I realized that the background stories of several of them are interconnected.”

As he explains, No Escape connects to the third-person video game The Last Watcher and the series of acrylic paintings The Mist, but the last two have a much more heightened post-apocalyptic marker.

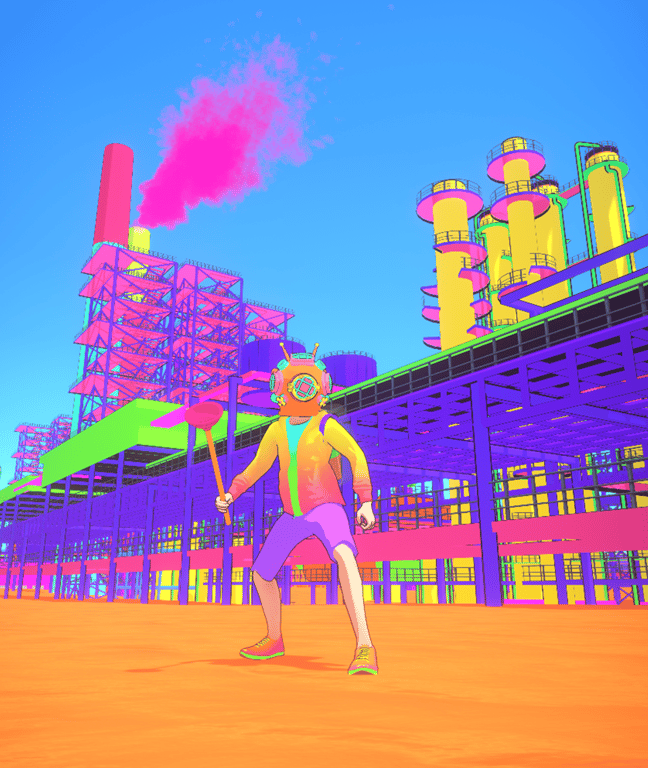

In The Last Watcher, the player engages in a series of adventures roaming through a wasteland dominated by massive factories, lifeless forests, and eerie theme parks.

The story goes that the few survivors of the apocalypse had to start over and implant microchips in their bodies to help them cope with their new reality, like changing their perception of the gray and devastated landscape they inhabit into a more bearable and intensely hued universe.

How far away from this doomsday scenario we are, neither Xia nor anyone can say, but for goodness’ sake, let’s not ask the A.I. bot.

Additional reporting by Lucas Tinoco; all images and videos via Xia Han