In the 18th and 19th centuries, when exploration was a hobby of the British upper classes, you’d regularly hear about the discovery of Brand New Civilizations — as though indigenous people’s generational histories did not pop into existence until someone with a pith helmet and a camera stumbled into the clearing. I had my own “Dr. Livingstone Presuming” moment this week, when I began to read headlines in such stalwarts of the British press as the Financial Times (as well as digital newcomers like The Verge) stating that the just-released film adaptation of The Wandering Earth marked China’s first tentative foray into sci-fi cinema, before scuttling back and forth between comparisons with contemporary American blockbusters and classic American sci-fi quicker than you can say “White Gaze Genesis.”

Three years ago, I began to give talks delivering a potted history of Kehuan (Chinese science fiction) and its significant contemporary developments. Many in the audience were thrilled to discover that Kehuan even existed. With the attention that Hugo Award winners Liu Cixin and Hao Jingfang brought to the genre, several novels and anthologies have since been published in translation in the West, with more on their way this year. I’ve subsequently been able to translate some new works into English, happy in the knowledge that Western readers were finally getting to know Kehuan, and that in a few years time, they may even get over their sense of novelty and be able to discuss these works purely on their own merits, as they do with other countries’ sci-fi.

Related:

“I Believe in the Individual”: Hugo Winner Hao Jingfang on Creativity in ChinaArticle Jun 13, 2017

“I Believe in the Individual”: Hugo Winner Hao Jingfang on Creativity in ChinaArticle Jun 13, 2017

Even with the growth in popularity of genre fiction and sci-fi around the world, readers are still only a small section of the general public, and readers of Chinese SF are a microcosm within a microcosm. However, when an influential book is made into a successful film, it becomes a loud voice breaking into the attention span of the general entertainment-seeking public. In the wake of The Wandering Earth‘s widespread recognition, I find myself on guardian duty again: defending history and works that risk disappearing in the swell of fresh interest, debunking this “White Gaze Genesis” approach to covering Chinese culture, and opening a portal to China’s tradition of science fiction cinema.

Science fiction in novels, manhua and essays has been a staple of Chinese literature for over 100 years

Science fiction in novels, Manhua and essays has been a staple of Chinese literature for over 100 years. Ever since Xu Nianci’s New Adventures of Mr. Conch (1905), and Lao She’s Cat Country (1932, now a musical, with a film adaption on the way), Chinese science fiction has given support to scientific endeavor, escapism from harsh times, and inspiration to generations of readers.

On film, there were several early attempts at sci-fi in the Chinese-speaking world, beginning with stop-motion animations and shadow puppetry employed to mimic space exploration. Early on, there were also some fantastically over-the-top full-length features, such as the Kaiju movie GuanYu Versus Aliens (aka The Big Calamity) by Taiwanese director Chen Hongmin, which hit the screens in 1976, proudly flaunting its blockbuster-size budget and claiming to be the first Chinese monster movie.

GuanYu Versus Aliens (aka The Big Calamity), dir. Chen Hongmin, 1976

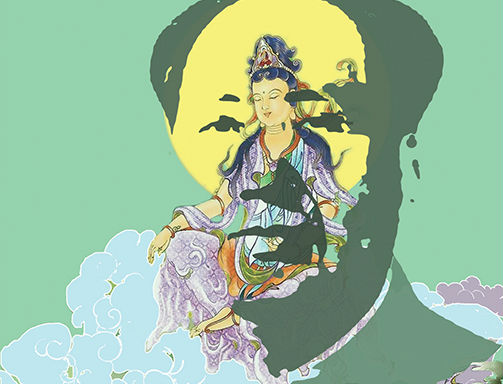

When an alien wreaks havoc in Hong Kong, who better to defend the city than the ancient figure of GuanYu, a larger-than-life hero and symbol of wrath and justice. This juxtaposition of classic myth and Futurism is something we’ll see more of — not just in film, but also in China’s fondness of building its reach to the stars on the foundations of its history.

It was only with the freedom brought about by China’s economic opening in the 1980s that, over a period of relative stability and comfort, moviemakers could explore a wider range of entertainment, including science fiction. A well-known classic from this period is the techno-thriller Death Ray on Coral Island, directed by Zhang Hongmei. It was released in 1980, only two years after the publication of the Tong Enzheng novel on which it’s based. Exploring war, peace, and world politics, it tells the story of an overseas Chinese engineer on his way to returning an atomic battery to the motherland. When he is marooned on a mysterious island by a laser tractor beam, he finds himself having to contend with a mad recluse, and the sinister aims of the umbrella corporation behind his experiments.

Related:

Yet Another Liu Cixin Novel is Getting Made Into a TV SeriesLiu Cixin’s “Ball Lightning” becomes the latest Chinese sci-fi novel to be green-lit for adaptationArticle Jul 10, 2019

Yet Another Liu Cixin Novel is Getting Made Into a TV SeriesLiu Cixin’s “Ball Lightning” becomes the latest Chinese sci-fi novel to be green-lit for adaptationArticle Jul 10, 2019

At the other end of the scale, the Kafkaesque dark comedy Dislocation (1986), directed by Huang Jianxin, tells the story of a scientist who, so bored with the academic protocol of endless meetings, creates a perfect android replicant of himself to attend the functions that he feels rob him of his time. Unfortunately, the android develops so quickly in its artificial intelligence that it tries to replace its creator.

Chinese sci-fi films weren’t just a vehicle for expressing deep meaning and technological angst. There has been a history of films aimed at children around the world, and whilst you could dismiss titles like CJ7 (Stephen Chow, 2008), you would also have to remove such great films as Explorers, Flight of The Navigator, and E.T. from the Western canon.

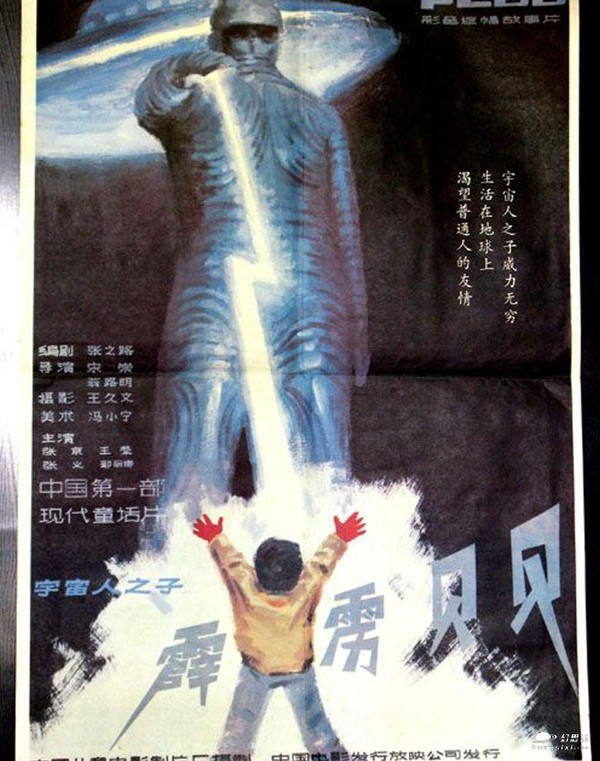

Well-loved for its humor and accessibility, Wonder Boy (1988), directed by Song Chong, tells the story of a child born with the ability to generate electricity. Bullied by neighbors and kept in isolation by parents who want to protect him, Bei Bei is a caring, mischievous little boy who uses his powers to help people and to have fun, in equal measure. When Bei Bei is taken in for experimentation, it is the handful of close friends he has made who come to the rescue — a format recognized by children from any culture.

Wonder Boy, dir. Song Chong, 1988

’90s Kehuan films channeled the grimdark movement, which affected so much speculative fiction of the time, and brought a slew of darker science fiction films from both the Mainland and Hong Kong. The Ozone Layer Vanishes (Feng Xiaoning, 1990) tapped into turn-of-the-century anxiety about the state of the environment as we headed towards the millennium. Professor Invisible (Zhang Zi’en, 1990) tells the story of an invisibility pill stolen by criminals, who use it to facilitate their reign of theft and violence. The film also examines the anonymity of people in an increasingly depersonalized society, and ends with the pill’s inventor concluding that society is better off without it.

This idea of “losing the self” reared its head in many Chinese sci-fi movies of the decade, including Kai-Ming Lai’s Hong Kong slasher Blue Jean Monster (1991) and Li Guomin’s Mainland production Warrior Revived (1995), where our antiheroes are returned from death, but in a manner that leaves them no longer really themselves. Whilst Blue Jeans Monster follows the traditional “what is this monster I have become?” route, Warrior Revived is a more interesting rendition, where a policeman wakes from a coma after a “miracle cure” only to find that the world around him isn’t the one he knew.

Warrior Revived, dir. Li Guomin, 1995

Even in the midst of rapid social change, Kehuan films still reached for traditions in storytelling. The outstanding Saviour of the Soul (1991) by David Lai and Corey Yuen is a visually original and stunning piece of wuxia sci-fi following the lives and loves of the mercenary city guardians of Hong Kong. As the story comes to a climax, we see the characters soaring through the air with cyberpunk swords, and the villains absorbing bioweapons to give themselves supreme strength and speed. The whole film borrows tropes and character archetypes from Jin Yong’s classic wuxia epic Condor Heroes.

More recently, Huayi Brothers (Tai Chi Zero, Mojin) backed the film Super Mechs (2018), which incorporates the classic wuxia element of brothers with fire and ice powers, separated at birth. The film wraps them in modern mech suits for some CGI-enhanced battling in a story that will obviously lead to the brothers reuniting, not only because of the unwritten rules of the wuxia genre, but… well, the rules of the robot genre, too.

Super Mechs, dir. Cui Junjie, 2018

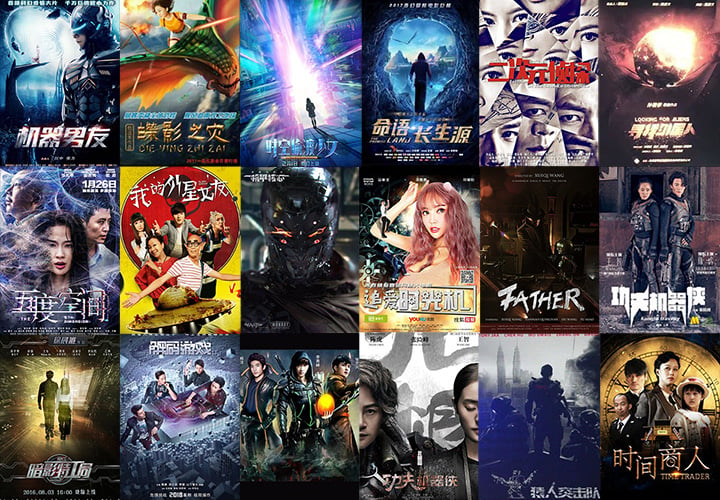

The increasing impact of China’s rapid growth over the last three decades has provided further fuel for the Chinese science fiction scene. Writers and artists are again taking inspiration from rapid macro social changes. With the rise of subcultures and the beginning of a culturally streamlined economy in 21st-century China, an explosion of genre movies has occurred, catering to young, tech-savvy, and independently wealthy youth who are as at home with anime and Western comics as they are with Three Kingdoms-style MMORPGs or TV costume serials.

With the rise of subcultures and the beginning of a culturally streamlined economy in 21st-century China, an explosion of genre movies has occurred, catering to young, tech-savvy, and independently wealthy youth

In the last few years, we’ve started to see films that have found unique viewpoints and subject matter, such as Target (Wang Jiang, 2014), which features a Chinese super-soldier solving international incidents, and The Shadow Agency (Xu Zhanhong, 2016), where the depleted resources of the planet, along with genetic manipulation, remain a concern.

Domestically funded by five media companies and starring Hong Kong comedian Eric Tsang Chi-Wai, 2018 film Mecha Core (aka Core of Powersuits) is set in 2069. The Clean Energy Revolution is threatened by greed as the world-saving McGuffin is hijacked by a fugitive scientist, who sells the material into the black market and uses it to complete his badass power suit.

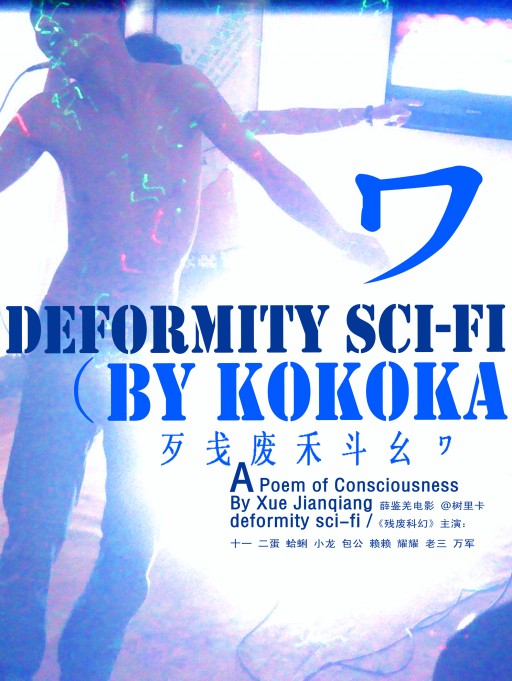

But these are not simply big studios aping Western output. With the increased accessibility of filmmaking, even art-house and independent filmmakers are dabbling in Kehuan. Deformity Sci-Fi (2013) is a peculiar, heady mix, shot in the Shanxi hometown of indie director Jianqiang Xue (a.k.a. Kokoka). It follows the lives and misdemeanors of a group of low-level wannabe gangsters, while the rest of the planet is gripped by first contact with an alien species. More traditional sci-fi films like The Sand Storm, a dystopian short about a city on the brink of a water shortage, are also finding not only their audience, but backers and talent in the digital landscape.

Deformity Sci-Fi, dir. Jianqiang Xue, 2013

Nowadays, the Kehuan genre is not only being adopted by comedies like My Alien Girlfriend and Robot Boyfriend, but as a vehicle to examine micro social issues and individual choice. In Time Cage (Jing Congjia, 2017), a hapless youth who lives off a stipend from his family is trapped in a time loop. At first he uses it to get rich, but when the plane carrying his girlfriend runs into danger, he must choose between keeping his fortune or giving it up to save her and the other passengers. Reset (Yi Hongcheng, 2017), produced by Jackie Chan, features a single mother and a physicist who develops wormhole transport technology. When her son is kidnapped and ransomed for the tech, the mother braves the wormhole herself in order to save her son.

These films, along with high school romances like The Girl From the Future and Love-Chasing Time Machine, as well as the much anticipated sequel to Wai Man Yip’s 2018 film Iceman, demonstrate that the “what if” and “what now” varieties of time travel sci-fi are still very much alive in China’s film industry.

Kung Fu Traveler

It isn’t only cinema screens that are being adorned with Kehuan movies. iQIYI (China’s equivalent of Netflix) has been producing its own original content for several years, including a series of sci-fi films. The first was Kung Fu Traveler (2016), about an engineer and an android warrior protecting humanity from hostile alien invaders by learning some of the greatest fighting skills in China’s history, bringing robotics, time travel, and aliens together in a Qing Dynasty kung fu flick.

China is drawing on Western influences for its science fiction, but not exclusively. With a long literary history, Chinese sci-fi is also self-referential. Low-budget noir The Secret of the Immortal Code (Li Wei, 2018) sees its heroine attempt to find a cure for her sister’s cancer by making a trip to her company’s arctic labs. Even though the cure is delivered, she remains unaware of its terrible side effects. The sinister scientist mastermind and isolated setting are wonderful references to Death Ray on Coral Island, whose tone the film also channels.

The Secret of Immortal Code, dir. Li Wei, 2018

The acclaim and visibility that Chinese science fiction has recently attained on the international stage has certainly encouraged the production of Kehuan movies. China’s current cinema-going boom, along with State controls on imported movies and the maturation of domestic filmmaking, mean that there is now an eager domestic market, and no need to tailor these films to foreign audiences. On the infrequent occasion when a Chinese blockbuster like The Wandering Earth tries to engage an international audience, it really is a flaw of cultural imperialism to not even acknowledge a filmic tradition that has gone from strength to strength over the past 40 years.

China’s current cinema-going boom, along with State controls on imported movies and the maturation of domestic filmmaking, mean that there is now an eager domestic market, and no need to tailor these films to foreign audiences

Those who grew up watching Kehuan classics will be enjoying the sci-fi boom of today, with a wide of range of what they have grown to love to choose from. We have never been able to chart the progress of Chinese cinema by the haphazard handful of international releases. To really understand contemporary Chinese film, we should look at what the Chinese are watching — to ignore the whole catalogue of a country’s production just because earlier works didn’t meet the foreign market tastes of the time is to unfairly condemn these classics to obscurity.

—

You might also like:

Author Xueting Christine Ni Explains the Culture Behind China’s Crowded PantheonArticle May 30, 2018

Author Xueting Christine Ni Explains the Culture Behind China’s Crowded PantheonArticle May 30, 2018

Liu Cixin’s Cosmic Sociology Brings Optimism to Chinese Sci-FiArticle Oct 31, 2017

Liu Cixin’s Cosmic Sociology Brings Optimism to Chinese Sci-FiArticle Oct 31, 2017

“The Wandering Earth”: Propaganda, Ratings Wars, and the Future of Chinese Sci-FiThe Liu Cixin adaptation just became China’s #2 all-time highest grossing film. What does it mean for the genre’s future?Article Feb 19, 2019

“The Wandering Earth”: Propaganda, Ratings Wars, and the Future of Chinese Sci-FiThe Liu Cixin adaptation just became China’s #2 all-time highest grossing film. What does it mean for the genre’s future?Article Feb 19, 2019