Although Psy’s “Gangnam Style” went viral in 2012, with covers and parody videos flooding YouTube, it’s only in the past couple of years that K-pop has been widely perceived to have broken into the cultural mainstream in the US and the rest of the (non-Asian) world. The reason? In short: BTS.

Big Hit Entertainment’s boy group have leapt from relative obscurity in the English-speaking world to appearing at major international music awards and on late-night TV shows in the US, while topping the Billboard 200 as well as Hot 100 charts across a host of genres in the past year. The group’s success has filtered down to other acts and led to K-pop being discussed as an unstoppable, brand-new musical — even cultural — phenomenon in some English language media.

But what about in China? The genre has actually been a huge (though largely hidden) part of pop culture here since the 1990s. And as a part of “Hallyu” — the “Korean Wave” of exported pop culture — K-pop has long enjoyed widespread popularity in mainland China. Yet the growth of K-pop in China has not been without complications and the perceived influence of Korea on Chinese youth has sparked frequent frictions.

You might also like:

The Search for China’s Next Big Boy Band is Emphasizing “Social Responsibility” Over SexinessAs China’s reality-show-pop-music industrial complex churns on, can iQIYI repeat the hype it created around last year’s readymade boy band NINE PERCENT?Article Jan 29, 2019

The Search for China’s Next Big Boy Band is Emphasizing “Social Responsibility” Over SexinessAs China’s reality-show-pop-music industrial complex churns on, can iQIYI repeat the hype it created around last year’s readymade boy band NINE PERCENT?Article Jan 29, 2019

From MTV to J-pop to K-pop

Back in the 1980s, South Korean record producer and music executive Lee Soo-man grasped the future of “seeing music” when MTV launched in New York. Learning from Japanese talent agency Johnny & Associates‘ idol-group-making model, Lee went back to Seoul and founded S.M. Studio in 1989, which is now known as S.M. Entertainment, an undisputed K-pop star-making giant.

S.M.’s first boy idol bands, H.O.T (1996) and Shinhwa (1998), as well as the first girl group, S.E.S (1997) were frequent subjects of Modern Music Scene, an early mainland Chinese music and entertainment magazine. This was how many Chinese millennials — this author included — were first exposed to K-pop. Yang Bo, a 31-year-old Beijinger working in HR, shares a similar experience: “I saw H.O.T and all those K-pop groups’ music videos on Channel [V] back in the ‘90s and 2000s,” she tells RADII. “Then I went to the music shop near my middle school to find new albums every week.”

Krystal, 27, who works in mobile advertising, grew up in a small town in rural Sichuan province, but K-pop’s reach was wide enough to find her there. “I was a big fan of TVXQ,” she says of another hit S.M.Entertainment boy group that debuted in 2003. “But back then there was not much we could do as fans in a small town in Sichuan. My friends and I could only find pirated albums, buy some magazines… and I know someone who wrote letters to the idols.”

When H.O.T held their first concert in Beijing in 2000 — still their only performance in mainland China to date — even people who were not fans became aware of the hype thanks to enthusiastic throngs of teenagers in the capital. In addition to the music, H.O.T and the groups that would follow in their footsteps attracted a huge fan-base through other key elements of the K-pop package, their street-dance-like stage performance and their “Visual-kei” fashion style.

Chinese Idols Go Seoul Searching

As this was happening, a few ambitious Chinese kids were preparing to take the next step: traveling to Korea to be trained within the K-pop idol-making system.

Before he started building his K-pop empire, Lee Soo-man surveyed his target audience — teenagers — on their ideal idol. The answer he got was simple and clear: “exceptionally good-looking members who can sing and dance,” according to a report from moonROK. This therefore became the foundational requirement for all future idols. Success as a K-pop star requires talent, hard work, and probably some subtle plastic surgery.

Before he started building his K-pop empire, Lee Soo-man surveyed his target audience — teenagers — about their ideal idol. The answer he got was simple and clear: “exceptionally good-looking members who can sing and dance”

One of the first Chinese trainees in the Korean idol-making system, who prefers to remain anonymous, tells RADII: “Everyone had to take vocal and dance training for the first few years. I went to Korean language class, too. Then we had individual training based on each person’s strengths and interests.” This trainee was scouted in 2004, when he was singing in his middle school’s choir. He dropped out of school, flew to Seoul, and received training under a major entertainment company for eight years.

Korea’s entertainment giants — mainly the “big three” of S.M., YG, and JYP — employ not only managers, agents, design coordinators, image consultants, marketing executives, and dance, vocal and acting instructors, but also lyricists, songwriters and arrangers, recording engineers, and choreographers to ensure that everything the idols present is original and fresh.

“They may design a persona for the trainee before [his or her] debut, but they never encourage individual personality,” the early Chinese K-pop trainee tells me. “Instead, they emphasize the group as a whole. Koreans have a strict sense of hierarchy. Someone used to shout at me, asking me to kneel down to the older Korean trainees, to show respect.”

Verbal and even physical abuse have long been criticized as the dark side of the K-pop idol-training system. Crazy Grace, a YouTuber and solo artist who was part of a popular girl group, has said in her videos that agents and managers would frequently check trainees’ phones, monitor girls’ weight, and forbid young trainees from exchanging anything more than a casual greeting with members of the opposite sex.

Rap Beefs and “Holy Wars”

Outside of the training system, K-pop has also courted controversy in China as it’s risen in popularity, even as more and more Chinese faces have appeared in group lineups.

As early as 2001, rapper MC Hotdog criticized the K-pop craze in Taiwan with a famous track called “Hallyu Invasion,” in which he boldly expresses his dissatisfaction with how easily “Korean singers make money in Taiwan.” Hotdog’s Mandarin raps have long carried significance in mainland China. “Hallyu Invasion” might be considered the beginning of an intense and uneasy relationship between “main rappers” in K-pop groups — that is, the member who handles the “rap parts” of the group’s songs — and underground rappers, a beef that continues to simmer in both Chinese and Korean hip hop music scenes to this day.

The most white-hot conflict regarding K-pop idol groups was triggered in Shanghai during the Expo 2010, when thousands of fans of Super Junior (an S.M. boy group starring the first Chinese idol, Han Geng), along with fans of former H.O.T member Kang Ta, gathered to form long lines for live concert tickets, a scene that ended in physical aggression (and numerous injuries) against the armed forces.

K-pop fans and their idols were subsequently targeted by furious Chinese netizens, mostly nationalists, and on June 9, 2010, a so-called “Holy War” began. Starting with World of Warcraft gamers posting on search engine Baidu’s message board, later tens of thousands of users broke into Super Junior fan boards, crashing them with millions of anti-idol comments and posts. On the same day, solo hackers and “Honker Union” members hacked Super Junior’s official website and social media accounts in China and in Korea.

This phenomenon would recur from time to time: over the following years, online fandom platforms for BigBang’s G-Dragon and the group EXO were attacked by hardcore football fans several times as well.

Related:

Tone-deaf Kris Wu Vocal Track Ravages Chinese Social MediaArticle Jul 27, 2018

Tone-deaf Kris Wu Vocal Track Ravages Chinese Social MediaArticle Jul 27, 2018

These conflicts between divided netizens haven’t changed much over the following years. K-pop fandom in China has consistently grown along with the overall Chinese market, and more Mandarin-language sub-units of major Korean groups have emerged, with more Chinese members getting in on the action. Super Junior-M and EXO-M (the “M” stands for Mandarin), for instance, minted the superstars Han Geng, Kris Wu, Lay Zhang and Lu Han, who still generate huge traffic across the Chinese entertainment industry today.

The “Hallyu Ban”

Nationalist netizens and teen superfans have their K-pop stories; the Chinese government has a different one.

After South Korea and the United States jointly announced the deployment of THAAD (Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense) in 2016, China opposed the alliance with “informal sanctions” on South Korea’s economy and culture. Although there was never an official “Hallyu Ban,” only a few Korean pop stars have been allowed to perform in China since.

“[A ban] is heartbreaking. Chinese fans’ biggest wish is to watch their idols’ concerts in mainland China.”

“It’s heartbreaking,” says Krystal, the K-pop fan from rural Sichuan, who started following BTS at the end of 2014. “Chinese fans’ biggest wish is to watch their idols’ concerts in mainland China.” Since BTS’s 2016 concert in Beijing, she has never been able to see them perform again. Beijinger Yang Bo has also been unable to see her favorite, YG Entertainment’s Big Bang, since 2016.

Related:

Chinese Fan Groups Break Records with Mass Purchase of BTS AlbumChinese fan groups organized mass purchases of BTS album Map of Soul: Persona, breaking records in the processArticle May 23, 2019

Chinese Fan Groups Break Records with Mass Purchase of BTS AlbumChinese fan groups organized mass purchases of BTS album Map of Soul: Persona, breaking records in the processArticle May 23, 2019

The Fan Economy

But absence makes the heart grow fonder, and many Chinese K-pop lovers will unconditionally spend their last cent for their idols. To understand K-pop’s popularity in China, it is essential to understand how deeply its fans have involved themselves in idol-making culture, and the incredible economics that backstop the entire industry.

Physical albums may largely be history in the era of digital music, but not for K-pop, an industry that stretches the meaning of the word. A K-pop “album” can mean a mini-album, an EP, a full-length, or a repackage of older material. It can be a group album, or special versions for each group member with different photo-cards inside (not to mention different units within bigger groups). The same goes for concert DVDs. If you are a fan of the whole group, then buying one album to support is enough. But if you have a “bias” within the group, then you probably need to buy additional copies of the album to collect individualized versions, or even all different versions if you’re a superfan.

As a “VIP” — the official title for Big Bang fans — it’s more convenient for Beijinger Yang to join an online fan club, where a club rep buys albums from Korea for all Chinese fans in the group. “I’ve bought every single album, including the DVDs. Then the digital copyrights were imported,” Yang says.

“Some core fans would buy dozens of the same album to boost the sales,” Krystal adds.

Even the original soundtrack of BTS’s recently-released interactive game BTS World is selling pretty well on Chinese streaming platform NetEase

But the most exciting and memorable event for any fan is always the live concert, where fans get to see their idols in person. This is also the busiest time for fan clubs.

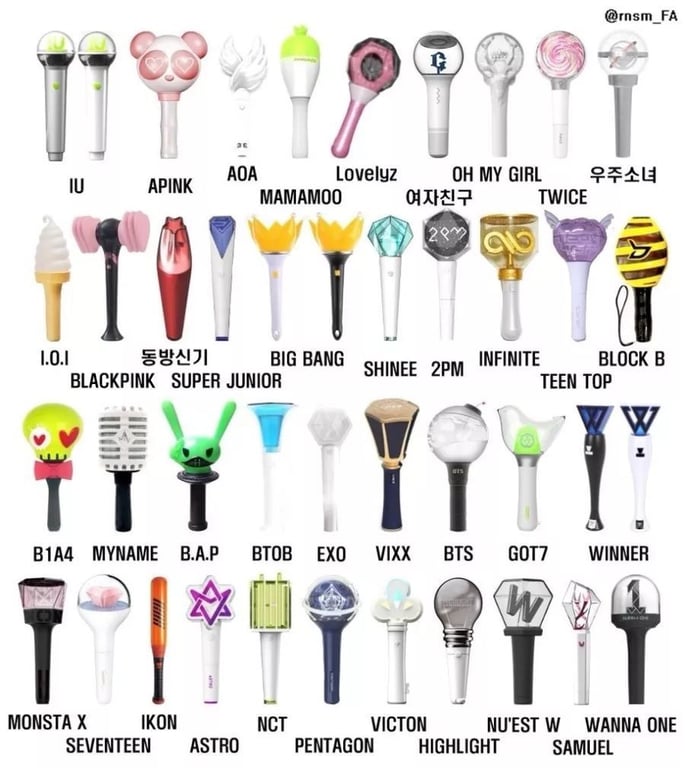

In a previous report on RADII, we explored how fan clubs can operate like professional companies. Organized into different “departments” within the group, a fan club member’s responsibilities for showing their idol love can include: scrambling to buy tickets before they sell out (usually within minutes); ordering official light sticks with the band’s official colors and shapes (like Big Bang’s crown-shaped yellow light sticks); collecting support banners from different fan clubs at the stadium; and memorizing an official fan chant (certain parts for fans to chant together at musical interludes). There are even tutorial videos for the fan chant and dance covers that group members can find online to prepare.

Yang Bo’s collection of support banners from different fan clubs for Big Bang’s 2012 Beijing concert

Official light sticks, by group

If one can’t make it to a live show, there are other ways to interact with idols offline.

Krystal from Sichuan lists some of the different kinds of events for fans to meet their idols: “Besides concerts, there also are CD-signing events, which are the most difficult to get into, as well as fan meetings, handshake meetups, and high-five meetups.”

K-pop fans at the Beijing airport (photo by the author)

Idol Hands and Livestream Wars

Some hardcore Chinese fans just fly to Korea to see K-pop stars in concert, and a few even find jobs and settle down in Seoul to follow their idols more closely. But most Chinese fans concentrate their energy on the ceaseless parade of opportunities to support (and do battle for) their idols online.

The most direct way to do this is to watch idols’ livestreaming videos on the app V Live, where fans can access paid membership perks and exclusive content, including special video clips of certain members or mini-variety shows. The entertainment agencies behind this programming also produce all kinds of reality shows to present every aspect of the idols’ life and work. A sub-genre of “pre-debut” shows even allows fans to follow trainees before they actually become idols.

Related:

Idol Hands: How China’s Super Fan Groups Make and Break Stars Via the Multi-Million Dollar “Fan Economy”Article Jan 07, 2019

Idol Hands: How China’s Super Fan Groups Make and Break Stars Via the Multi-Million Dollar “Fan Economy”Article Jan 07, 2019

The most time-consuming — yet crucial — element for fans to make their idol group stand out from the crowd is voting. Music Network’s M Countdown, KBS’s Music Bank, MBC’s Show Champion, and SBS MTV’s The Show are major weekly music programs, and battlefields for fans to vote up their favorites. The criteria for each show to decide the top 10-50 acts of the week vary slightly, but they are all based on combining data from the artists’ digital sales, physical sales, social media stats, netizen rankings, and streaming numbers.

Big annual music awards like Mnet Asian Music Awards, Golden Disk Awards, and Melon Music Awards also factor the fans into the process of selecting the “Daesang” (Grand Prize or Artist of the Year) title.

There’s really a lot of work involved with being a proper K-pop fan

There’s really a lot of work involved with being a proper K-pop fan. Buying digital and physical albums, and voting in real-time while the groups perform live on TV, are merely basic requirements. Fans often have parallel accounts on streaming platforms like Melon, Mnet, Genie, and YouTube in order to stream the music and videos day in, day out, to aggregate streaming data and to make their idol an “All-Kill” — a phrase that describes when a specific artist or song is #1 on all Korean charts simultaneously.

As many of these streaming services are blocked within China, Chinese fans must surmount the additional barrier of using VPN software to receive updates and join in the fight. Streaming accounts can also be found for rent on Taobao, the major Chinese ecommerce platform. Fan clubs offer detailed tutorials for every single step of the upvoting process. This process turned some heads last November when former EXO member Kris Wu dropped his latest album, and jumped ahead of Ariana Grande on the Apple Music chart with the help (and multiple registered accounts) of EXO fans:

Kris Wu Controversially Pulled from iTunes Top Spot as Twitter Asks, “Kris Who?”Amidst allegations of fraudulently boosted iTunes sales for Wu’s new album, online reactions range from “who the f*** is Kris Wu?”, to the vaguely Sinophobic, to the outright racist — but did Chinese bots really boost his stats?Article Nov 07, 2018

Kris Wu Controversially Pulled from iTunes Top Spot as Twitter Asks, “Kris Who?”Amidst allegations of fraudulently boosted iTunes sales for Wu’s new album, online reactions range from “who the f*** is Kris Wu?”, to the vaguely Sinophobic, to the outright racist — but did Chinese bots really boost his stats?Article Nov 07, 2018

Inter-fan-group wars on social media can be especially cruel, because different groups’ method of or reasons for showing their loyalty can differ wildly. There are group fans, individual member fans, fans of different imaginary “couple” members from a group, fans of being an imaginary “girlfriend” of the group members, fans of being an imaginary “mom” of the group members, and so on. On top of defending attacks from outside the K-pop community, stans of different groups or different members within the world of K-pop can be sworn enemies. “Sasaeng” fans, almost equivalent to stalkers, are the common enemy to every type of fan.

Take EXO, for example: after they welcomed President Trump and Ivanka Trump at the Blue House with a signed album, and Ivanka expressed how her daughters love EXO, a war was triggered on Weibo. Who is the most popular K-pop boy band? Who should represent K-pop around the globe? EXO-Ls (EXO fans) and ARMYs (BTS fans) exchanged constant arguments about these issues.

“I received notice from an ARMY WeChat group calling on fans to support on Weibo that time,” BTS fan Krystal says. “Generally speaking, comment control is also important. Some anti-fans will search something bad about BTS members on Weibo to make the auto-complete search results look bad, so fans have to search more about something good about the idols to make it right.”

But… Why?

It seems that K-pop fans would do anything for their idols. But what do they expect in return? What part of K-pop is so appealing to demand this level of support?

On top of “girlfriend fans” and “mom fans,” who might get a kick out of the role-playing aspect of their fandom, there are many more rational fans, like my interviewees.

Krystal has recently experienced a change of mindset. “I used to see the idols as my ideal boyfriend type when I was a teenager, but now I just feel speechless when I see young girls being surprised about their idols doing this or that. I mean, what you see is just their public persona. No need to be so serious. Following K-pop is more like a hobby that I’m used to, or just a lifestyle to me now.” She also jokes, “BTS is so popular now that I’ve almost given up following them.”

Related:

The Year In “Little Fresh Meat”: Young Chinese Male Stars Who Killed It In 2019Whether they’re part of a CIA plot or simply the sexy stars Chinese fans want, it’s been a big year for these male celebsArticle Nov 26, 2019

The Year In “Little Fresh Meat”: Young Chinese Male Stars Who Killed It In 2019Whether they’re part of a CIA plot or simply the sexy stars Chinese fans want, it’s been a big year for these male celebsArticle Nov 26, 2019

“K-pop is more diverse and higher-quality, and has developed longer compared to Chinese [pop] music,” says Big Bang fan Yang. “The idols are trained to be multi-talented in their performance [singing, dancing, etc], and to be celebrities, to meet the market need… You can see that they’ve invested a lot in the costumes, the style, the stage, the production of every aspect of their appearance.”

No matter how K-pop’s story will play out in mainland China in the future, its global journey has just begun, with millions more fans flocking in from different parts of the world.

And Chinese fans will always be a part of it.