In late 2018, Chinese tech giant Tencent announced that it had raised around 1.1 billion USD via an IPO in the US that valued its music streaming service at 21.3 billion USD (when Spotify went public last spring, it was valued at around 28 billion USD). At the end of February, it was announced that the company was making a “strategic investment” in indie streaming rival Douban FM, a service we once praised for its “artist-first” approach and which recommends music algorithmically based on the users’ choices and Douban’s album ratings and reviews. And just last week, Reuters reported that Tencent was mulling a 23 billion USD bid for “up to half” of iconic label Universal Music, home to the likes of Lady Gaga and Taylor Swift.

The moves are Tencent’s latest in China’s streaming wars, and part of a bigger picture that is seeing the makers of WeChat attempt to obliterate the competition in the music sphere. But this goes beyond mere boardroom vindictiveness — the tremors are being felt across China’s music industry and even in indie circles, with a profound impact upon artists and fans.

To make sense of Tencent’s ambitions and recent moves in the space, let’s take a look at the current music streaming landscape in China via the major players.

The Key Competitors

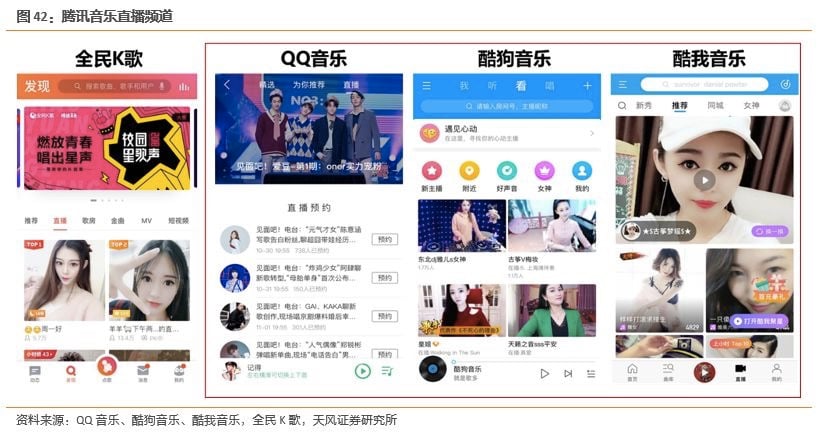

The biggest one is, undoubtedly, Tencent Music Entertainment Group (TME), which was founded in 2016 with the merger of Tencent Music (who owned QQ Music as well as online karaoke app KG) and China Music Corp, also known as Ocean Music, which began as a copyright agency and owned two leading streaming platforms at the time in Kugou Music and Kuwo Music.

Kugou and Kuwo were founded in the early 2000s, as was QQ Music, and taken together these platforms command a huge market share. According to its own official introduction, TME currently has overall 800 million Monthly Active Users, while also owning the rights to over 20 million songs and operating cooperation agreements with more than 200 music labels including SONY, Universal, and Warner. Kugou Music, whose slogan is “Just So Many Songs”, claims that there are more than 30 million licensed songs on their platform alone.

Related:

Digitally China Podcast: Tencent Music vs SpotifyArticle Jan 03, 2019

Digitally China Podcast: Tencent Music vs SpotifyArticle Jan 03, 2019

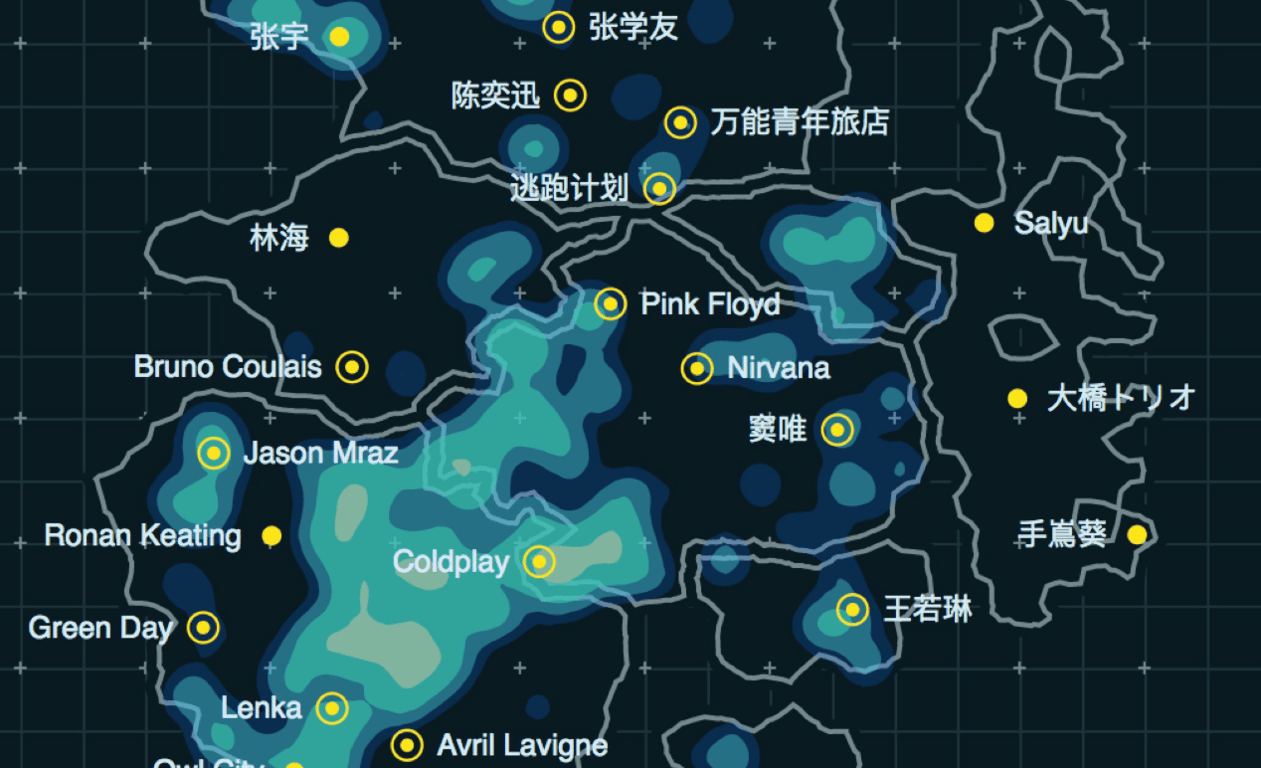

Tencent doesn’t quite have a monopoly on China’s streaming market just yet, however. NetEase Music (music.163.com) might be the most competitive of the alternatives that are still hanging in there. Founded in 2013, NetEase claims to have 600 million registered users and to have had 1.676 million MAU in the first month of 2019. The music platform fought its way out by building an active music community as well as the biggest user-generated content platform, where millions of music reviews and playlists are generated every day.

Having given up on their own music platform, Chinese tech behemoth Baidu invested in NetEase last year and helped the latter to reach a broader scope of users, as well as to cultivate more indie musicians who create original works exclusively for the platform.

Related:

Chinese tech conglomerate NetEase has been quietly raising pigs for eight yearsArticle Oct 29, 2017

Chinese tech conglomerate NetEase has been quietly raising pigs for eight yearsArticle Oct 29, 2017

So Tencent and Baidu have a hand in the music streaming game. Almost feels like we’re missing someone, right? Naturally, Alibaba have a horse in this race too. Xiami Music was founded in 2006 and bought by Ali in 2013. While it seems far behind in terms of user numbers, the user stickiness of Xiami is actually the highest among the aforementioned platforms, which is probably due to its focus on niche music since day one. Xiami itself likes to emphasize “profession” and “precision.”

How a Piracy Crackdown and Copyright Wars Changed the Picture

Time was, finding pirated music on the Chinese internet was straightforward. Even seemingly legitimate streaming platforms could be found sharing albums from international and domestic artists on the day of their release, regardless of whether they actually held the rights to them. No more.

In 2015, the National Copyright Administration of China compelled all music platforms to “stop sharing unauthorized music works” and to take down any media that might infringe copyright. A mad scramble to secure music copyright agreements with labels ensued. Most of the major players, like Baidu Music, failed. Only a few survived, and Tencent in particular cleaned up.

When you own the rights to the music that fans want to hear, users naturally follow. In a BigData-Research report on MAUs (monthly active users) on digital music platforms released in February 2018, QQ Music topped the chart with 329.62 million users; Kugou wasn’t far behind, with 303.73 million. App user behavior data offered by iResearch shows that in January 2019, Kugou had taken the number one spot with 323.88 million MAUs, followed by QQ Music (323.13 million) and Kuwo (177.64 million).

(Interestingly, the three TME music websites ranked lower than those for NetEase and Xiami, as the second chart below shows, although the number of website users is far behind that of those using apps. The middle columns below show number of users in tens of thousands.)

After two years of escalating lawsuits and copyright bidding wars, the National Copyright Administration of China once again intervened. In 2017, they interviewed all of the major music platforms and music record companies, and led discussions that eventually broke most of the copyright barriers among TME, NetEase and Alibaba Music in 2018. What this now means is that these music platforms share 99% of their owned copyrights, meaning they have fairly similar catalogues. (That last 1% might be the reason why 78.2% of Chinese music listeners still maintain more than one music app, however.)

So Where Next?

In addition to buying up some of the other leading players, Tencent has begun to look to other forms of differentiation for their music arm — something which may well be part of the reasoning behind the company’s rumored bid for Universal.

This is where Tencent’s “neo-culture creativity” strategy comes into play, which is kind of corporate-speak for “linking resources in different market sectors”. So on top of purchasing copyrights from record labels and agencies, TME has been cooperating with Tencent Video on Rap of China-like TV competitions such as RAVE (an EDM contest) and The Coming One (an American Idol-esque one).

Related:

TV Giants are Hoping Rock Bands and DJs Will Give Them the Next “Rap of China”Article Nov 13, 2018

TV Giants are Hoping Rock Bands and DJs Will Give Them the Next “Rap of China”Article Nov 13, 2018

It’s not just TV tie-ins, either. All three major platforms have launched a range of musician contests in recent years, in addition to establishing sub-labels that focus on different genres, such as the NetEase-launched competitions Fever Plan (electronic) and Project Stone (folk), TME’s Force Music Plan, and Xiami’s Project XG talent search and electronic label LiquidState, which features investment from SONY.

Such promotional activities could be key in establishing a competitive advantage. According to the Communication University of China’s research, in considering which music platform to choose when it comes to registering and releasing their own works, the main factor in making a decision for artists comes down to how capable that platform is perceived to be of promoting their works to the right audience. According to the same research, only 1.65% of artists prioritize financial return above other factors.

Can Video Save the Radio Stars?

That apparent ambivalence regarding compensation for their art may be for the best. While Spotify regularly faces criticism from artists for how little they see in financial rewards from having their music stream on the platform, the Swedish company at least has 46% of its users paying for subscriptions to generate revenue. As of September 2018, less than 4% of TME’s users were paying for its services.

Digital music made up 75% of the Chinese music industry’s revenue in 2017, with musical performances bringing in 22.5% and physical record sales just 0.8%. But with so few paying for streaming services, the issue of compensation for artists could be even more acute in China than in markets where Spotify is dominant.

One apparent attempt to address this appears to be a move by streaming platforms to try and harness China’s penchant for video streaming apps. Arguably the biggest name in this field, TikTok, also recently announced that it was moving the other way by setting up its own music label.

TikTok Drops an Album, Vows to “Help Musicians Be Heard”With the release of its first music compilation, is short video platform TikTok setting its sights on China’s music industry?Article Jan 23, 2019

TikTok Drops an Album, Vows to “Help Musicians Be Heard”With the release of its first music compilation, is short video platform TikTok setting its sights on China’s music industry?Article Jan 23, 2019

Chinese users’ habit of paying for and during video streaming (via one-off fees and “gifts” for presenters) has been widely cultivated, and all three of the TME music streaming apps, as well as NetEase Music, now feature video streaming sections.

Where things go from here and whether more alternative players can survive amid Tencent’s apparent push for dominance remains to be seen. But whether a bid for Universal eventually materializes or not, it’s clear the tech giant has some ambitious plans for its music arm in China. And it’s unlikely we’ve seen the last of such moves just yet.

You might also like:

Digitally China Podcast: Tencent Music vs SpotifyArticle Jan 03, 2019

Digitally China Podcast: Tencent Music vs SpotifyArticle Jan 03, 2019

Douban FM is Fighting the Music Streaming Wars with Innovation and an Artist-First ApproachArticle May 02, 2018

Douban FM is Fighting the Music Streaming Wars with Innovation and an Artist-First ApproachArticle May 02, 2018

Is the US Ready for an All-Chinese Content Streaming Service?New streaming platform BAMBU is hoping to bring Chinese movies and TV shows to US audiencesArticle Feb 13, 2019

Is the US Ready for an All-Chinese Content Streaming Service?New streaming platform BAMBU is hoping to bring Chinese movies and TV shows to US audiencesArticle Feb 13, 2019