100 Films to Understand China: Animation

These 10 films provide an illuminating cross-section of the last 50+ years of Chinese cinema in the language of an often under-valued medium

The list below is part of RADII’s 100 Films to Understand China.

Animation

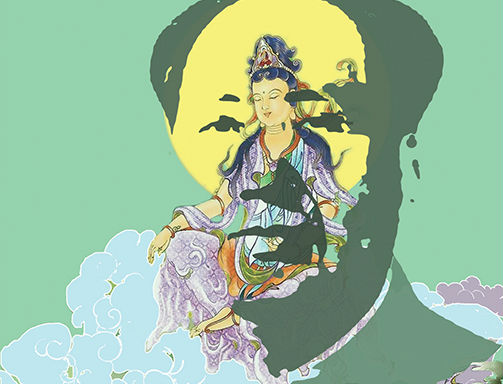

Chinese animation has a long history of providing safe harbor for forms and ideas that could not be as easily expressed in live-action productions, such as the rebellious individuality of long-cherished dramatic figures like the Monkey King and folk deity Nezha. As Variety‘s Rebecca Davis observes below, “animation in China has typically been seen as purely for young children, allowing more daring content to slip through the cracks in this genre.”

From early paper-cut animations by the pioneering Shanghai Animation Film Studio, to the box-office-crushing, 3D-animated blockbusters of recent years, these ten films provide an illuminating cross-section of the last 50+ years of Chinese cinema in the language of an often under-valued medium.

Princess Iron Fan (Wan Laiming, Wan Guchan, 1941)

The first-ever Chinese animated feature film is based on stories adapted from the epic 16th century novel, Journey to the West. Princess Iron Fan duels with Sun Wukong, with her fan required to quench flames around a village. The film was directed by Wan Laiming and Wan Guchan, two of the hugely influential Wan brothers who are considered the first Chinese animators.

Linda C. Zhang, PhD candidate, UC Berkeley: Proclaimed the first major length animated film produced in mainland China, Princess Iron Fan is a trippy animation that is fun for all to watch. It adapts the chapter “Sun Wukong borrow the Iron Fan Three Times” from Journey to the West. There is much to look out for and to listen to in this movie, such as rotoscoped motion-capture, famous voice actors from the Shanghai scene, and allusions to 20th-century war.

WATCH IT YouTube

Pigsy Eats Watermelon (Wan Guchan, Wan Laiming, 1958)

Another early Chinese animation with a story adapted from Journey to the West, 1958’s Pigsy Eats Watermelon is remembered for its use of an innovative paper-cutting style.

Linda C. Zhang: Perhaps one of the most beloved of the “paper-cutting style” animation from Shanghai Animation Film Studio. Has some great songs sung by the character of Pigsy, from Journey to the West, as he shirks his duties and tries to sneak some watermelon while pretending to be working hard.

WATCH IT YouTube

Havoc in Heaven (Wan Laiming, Cheng Tang, 1963)

Another epic from the Wan brothers, Havoc in Heaven was first conceived as a story in 1941, but delayed because of the Japanese invasion of Shanghai. The story is yet again based around Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, who here rebels against the Jade Emperor.

Phoebe Long, screenwriter: Excerpts from the Chinese classic Journey to the West make up the story, the characters are vivid and the painting style is born out of the brush strokes of China. It can be described as a purely Chinese animation from the outside to the inside. In my mind, this cartoon has not yet been surpassed.

Muhe Chen, filmmaker: Most Chinese animation addresses classical myths and folk tales instead of real-world events. But they still tell [us something about the] ideology and value behind the symbols. The idea behind the character of the Monkey King is about rebellion and individuality, as opposed to most animations, which promote good ethics and collectivism.

Michael Berry, Professor of Contemporary Chinese Cultural Studies and Director of the Center for Chinese Studies, UCLA: This animated film adapted from the classic novel Journey to the West is basically the “origin story” of the Monkey King, Sun Wukong. Although the story has been adapted countless times since, Havoc in Heaven remains the gold standard in terms of its artistry, playfulness, imagination, and beauty.

WATCH IT YouTube

The Peacock Princess (Jin Xi, 1963)

A prince stumbles across a group of women who can transform into peacocks, and falls in love with one. Threatened by death and war, the couple find ways to overcome treachery. Based on a story from the Dai minority from southwestern Yunnan province.

Linda C. Zhang: One of the rare major-length animation films, Peacock Princess is based on a Dai minority narrative poem, “Zhao Shutun.” The film follows the story of the prince Zhao Shutun falling in love with a heavenly princess who can take the shape of a peacock, and the subsequent trials they go through to be together. It is a masterpiece of puppet animation, full of beautifully detailed sets, and exquisite expressions by the puppets.

WATCH IT YouTube

Nezha Conquers the Dragon King (Yan Dingxian, Wang Shuchen, Xu Jingda, 1979)

Based around stories from another popular 16th Century novel, Investiture of the Gods, Nezha Conquers the Dragon King is a classic that eventually screened at Cannes Film Festival and later on BBC Two.

Xueting Christine Ni, author and speaker: Nezha Conquers the Dragon King stylistically takes a lot of inspiration from traditional art and one of the most accessible stories of that era. Considering how well the new animation has done in China and around the world, it’s well worth seeing the original, which holds up very well and is a good reminder of the time that China was a leader and pioneer in Asian animation production.

WATCH IT YouTube

Three Monks (Xu Jingda, 1980)

Produced by Shanghai Animation Film Studio, this film won the Best Animated Film prize at the inaugural Golden Rooster Awards in 1981, plus four international awards including a Silver Bear for Short Film at the 32nd Berlinale in 1982.

Emma Xiaoming Sun, writer and producer: Though the title and story derive from a Chinese saying, this is a silent film with no dialogue. The full saying is “一个和尚挑水喝,两个和尚抬水喝,三个和尚没水喝,” which translates to “one monk carries two buckets of water; two monks share the burden; if there are three monks, no one fetches the water.” This is an exceptional visual comedy that sparks old wisdom. The art direction is extremely simple, but unquestionably has its own unique style. With traditional instrumentation providing both the score and sound effects, this film presents an audio-visual aesthetic that stems from Beijing opera but lands in the beyond.

WATCH IT YouTube

Lotus Lantern (Wang Dawei, 1999)

After spending four years in production, and utilizing vast resources including top-tier voice actors and pop singers from mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan for its soundtrack, Lotus Lantern hit theaters in 1999. It marked a sea change in Chinese animation, earning 2.9 million RMB at the domestic box office.

Emma Xiaoming Sun: Lotus Lantern holds an epoch-making significance as the first major commercial Chinese animated film. Such a film was inevitable: Disney’s Lion King earned massive box office success in China in 1994, becoming the highest-grossing Western film at the time. Why couldn’t China make its own? The vaguely romantic soundtrack was so popular across an all-ages audience that it could turn a rowdy elementary school campus into a quasi-religious sing-along, and could regularly be heard in the back seat of a late-night cab ride. The film hasn’t exactly aged well — traces of Disney’s influence are far too obvious, often leading to confusing and embarrassing results. It was a desperate attempt to succeed in the market by Shanghai Animation Studio, and unfortunately, it also serves as the storied company’s last hurrah, as nothing memorable came out of the studio afterwards.

WATCH IT YouTube

Big Fish & Begonia (Zhang Chun, Liang Xuan, 2016)

This 2016 film, about a teenage girl who travels the world as a dolphin, is based on ancient Chinese myths, but technically and beautifully executed in a completely fresh, contemporary fashion.

Xueting Christine Ni: China has a long tradition of taking inspiration from its Shen Hua (mythology) for the creation its Dong Hua (animation), from classics such as the 1964 Uproar in Heaven and Nezha Conquers the Dragon King (1979), to The Calabash Brothers (1986) and recent renditions of Investiture of the Gods. Certain deities, such as ones that have evolved with urban entertainment, tended to be focused on. Big Fish & Begonia takes a fresh angle on the subject. The story is set in the Undersea, the world of Chun, heroine of the story. Based on the concept Gui Xu from the 4th to 5th century BCE Daoist text Lie Zi, Undersea is the final resting of souls and has existed for millennia, its inhabitants keeping the order of Nature, the natural course along which all things run in the human world, also known as the Dao. Daoism is one of China’s oldest indigenous belief systems. And most of the creatures represented in [Big Fish & Begonia] are China’s oldest deities that existed centuries before the Monkey King sprung from the minds of storytellers and Buddhism introduced Nezha’s prototype into China. [read more]

WATCH IT Netflix | Amazon Prime

Related:

Have a Nice Day (Liu Jian, 2018)

Praised by famed Chinese director Jia Zhangke as a landmark in Chinese animation, Have a Nice Day is a dark comedy that made waves for its alternative story and style, eventually picking up a Golden Horse for Best Animated Feature.

Krish Raghav, artist and writer: A rare full-length, unashamedly “alternative” dark comedy, warts and all, that somehow secured a theater release on the mainland. Have a Nice Day is funny, blunt, vulgar, and features a great soundtrack by Shanghai Restoration Project.

Linda C. Zhang, PhD candidate, UC Berkeley: Liu Jian’s hand-drawn animations show what is possible with mixing genres and forms, and share a sense of dark humor about contemporary life in China. Watch for some absurd situations (usually surrounding the plot device of a container of cash) that usually end up in stand-offs and violent conclusions.

WATCH IT Amazon Prime

Ne Zha (Yu Yang, 2019)

The release of Ne Zha was greeted by waves of excitement in the animation community, with the film becoming the second-highest-grossing film in Chinese box office history, spurring massive interest in animated movies across the country.

Emma Xiaoming Sun: Invested and distributed by entertainment giant Enlight Pictures, Ne Zha took five years to complete, with a crew of 1,600 animators. Those efforts paid off spectacularly. Reviews were overwhelmingly positive, and the film was dubbed “the glorious light of domestic anime” [国漫之光 guoman zhiguang] by netizens and media alike — though this is a term that emerges every time a domestic anime production hits screens, reflecting how the market is usually dominated by animations from the US or Japan.

WATCH IT Netflix

More Films to Understand China