Sometime after the grey area at the end of the ‘90s, but before and the full swing of the 2000s, the window for rap commercials in the US closed forever.

That is, commercials in which the advertising copy is rapped directly to the viewer, endorsing the product’s qualities through beat and rhyme. Who could forget this timeless Reese’s Puffs spot, where this kid puts down a dirty south banger for his chocolate peanut butter breakfast:

Today, having someone spit bars for your product comes across as corny, or try-hard. Rap commercials have to take a tongue-in-cheek approach, and rely heavily on celebrity presence (see: Superbowl ads). But in China, hip hop has only recently become mainstream enough to earn itself a seat at the product placement pantheon.

Following the smash success of reality TV show Rap of China, which we’ve been following in great detail, ad execs, brand directors, and general folks who make a living convincing others to buy things, have all leapt onto the unsuspecting genre as a communication medium for the elusive younger generation of consumers.

“Rap of China played a major role in bridging the gap between rap culture and mass public audiences, leading brands to an untapped gold mine,” explains Jonathan Chan, Creative Director at Shanghai-based boutique advertising agency Createc. “Audience awareness of rap and other street culture is all on the rise — it makes it easy to attract younger target audiences, while also giving brands a more approachable and appealing image. They’re saying ‘hey, we get you’, to a demographic with high willpower and high spending power.”

Surprisingly, when it comes to rhythmic appeals to viewers, the State government seems to be way ahead of the game. Interesting to say the least, since some of this was just months before China’s governing media body decreed its so-called “hip hop ban” (which ended up really not being much of a ban at all).

CCTV released an animated, anti-corruption rap video. There was also a rap advocating Karl Marx as someone who really “gets” millennials (“I don’t read magazines, I read Marx and I was born in the 1990s / I am your Bruno Mars / But you are my Venus / My dear Marx”). There was the iconic, rap-rock music video celebration of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, complete with trap breakdowns, awkward teen dance moves, and awkward teen everything else.

This OBOR-Themed Rap-Rock Earworm Won’t Leave Your HeadArticle Dec 05, 2017

This OBOR-Themed Rap-Rock Earworm Won’t Leave Your HeadArticle Dec 05, 2017

And of course we have to mention the students of the Communist Youth League who banded together to express their views in rhyme ahead of the 19th party congress. Even more impressive (?) is CD REV, the softest rap crew of them all, whose songs all carry rather straightforward political messages, and are frequently promoted on official media outlets. So despite current State leanings, we think it’s safe to say the Party itself was a big innovator in laying the foundation for China’s ongoing stream of rapped commercials.

CD REV: *beat drops* “How many times do I have to warn you, my lovely little neighbor boy?”

That was all before Rap of China, the hit TV show that single-handedly made hip hop into a truly mainstream phenomenon. We’ve covered it pretty closely, so we won’t go into terrible detail about what exactly that means, but the broad strokes are that young people decided they were into hip hop, old people finally had a chance to realize what hip hop looked like, and the program’s surprisingly wide-reaching influence made rap music a hip wave that was easy to ride.

When the term “freestyle” reached a top-trending position on Weibo, the nation was suddenly inundated with “freestyle” fast food combos, art exhibitions, and mosquito repellants. For the show’s second season, that suddenly ubiquitous, Kris Wu-sparked buzzword was “skr“.

It’s All “Freestyle” – How Meaningless English Buzzwords Define China’s Pop Culture TrendsArticle Aug 01, 2017

It’s All “Freestyle” – How Meaningless English Buzzwords Define China’s Pop Culture TrendsArticle Aug 01, 2017

But more crucial here than Rap of China ’s promotion of general hip hop culture, were the mid-program rapped endorsements of the show’s sponsors. The first season’s sponsors — McDonald’s, Nongfu Vitamin Water, Absolut Vodka, and others — all received glowing lyrical reviews of their products.

Imp smoothly segues from rapping a recap of the previous episode, to rapping about Nongfu Vitamin Water

“Hip hop is a vitamin / boundless energy that never stops / Nongfu Vitamin Water / the celebrity blogger opens up the attack engine”

(We’ve confirmed with native Chinese speakers that this line doesn’t make any more sense in Chinese than it does in English.)

After the show blew up, producers spared no effort in squeezing product placement money out of brands, all eager to get in on the latest iteration of youth culture. Enter the “digital spots” — low-budget, solo music videos by the show’s finalists, each endorsing a different product. BrAnT.B crooned about Nivea Men’s skin cream from inside a vaporwave whip, surrounded by classical busts. PG One, the overnight sensation who experienced an equally-overnight fall from grace, delivered League of Legends bars in an ad for Alienware computers. Sena did an overly cute rap about EOS lip balm.

After Rap of China proved the commercial viability of hip hop advertising, there was no turning back. In the months that followed the show’s debut:

1. KFC came for the McDonald’s China-localized-American-fast-food-hip-hop crown, with this spot for their new fried shrimp item.

2. Higher Brothers frontman Masiwei did an A+ commercial about visiting home for the holidays, where only an ice cold Sprite and flaming hot rap bars could save him from his family’s questions about his girlfriend and salary.

3. MC Jin, aka Rap of China ’s masked “Hiphopman”, went full force, rapping lengthy product endorsements for Alipay, Harbin Beer, and Liby soap. “There’s a kind of lifestyle I have to tell you about,” MC Jin explains in the latter. “Just the same as hip hop — it’s called ‘Greenstyle.’“ We’re not sure what that means, but you can watch through an entire playlist of MC Jin’s advertisement portfolio here.

Chinese App Rivalries Heat Up with Cashless Raps and Bike DiplomacyArticle Aug 03, 2017

Chinese App Rivalries Heat Up with Cashless Raps and Bike DiplomacyArticle Aug 03, 2017

At some point, hip hop’s time in the spotlight will fade, and China’s advertisers will move onto the next trend in their desperate race to speak to the country’s young consumers. But for now, the stream shows no sign of slowing.

Countless commercials in beat and rhyme, and rest assured, they get worse each time.

—

You might also like:

Meet the Women of “Rap of China” Season 2A look at the female rappers taking aim at China’s hip hop sceneArticle Aug 06, 2018

Meet the Women of “Rap of China” Season 2A look at the female rappers taking aim at China’s hip hop sceneArticle Aug 06, 2018

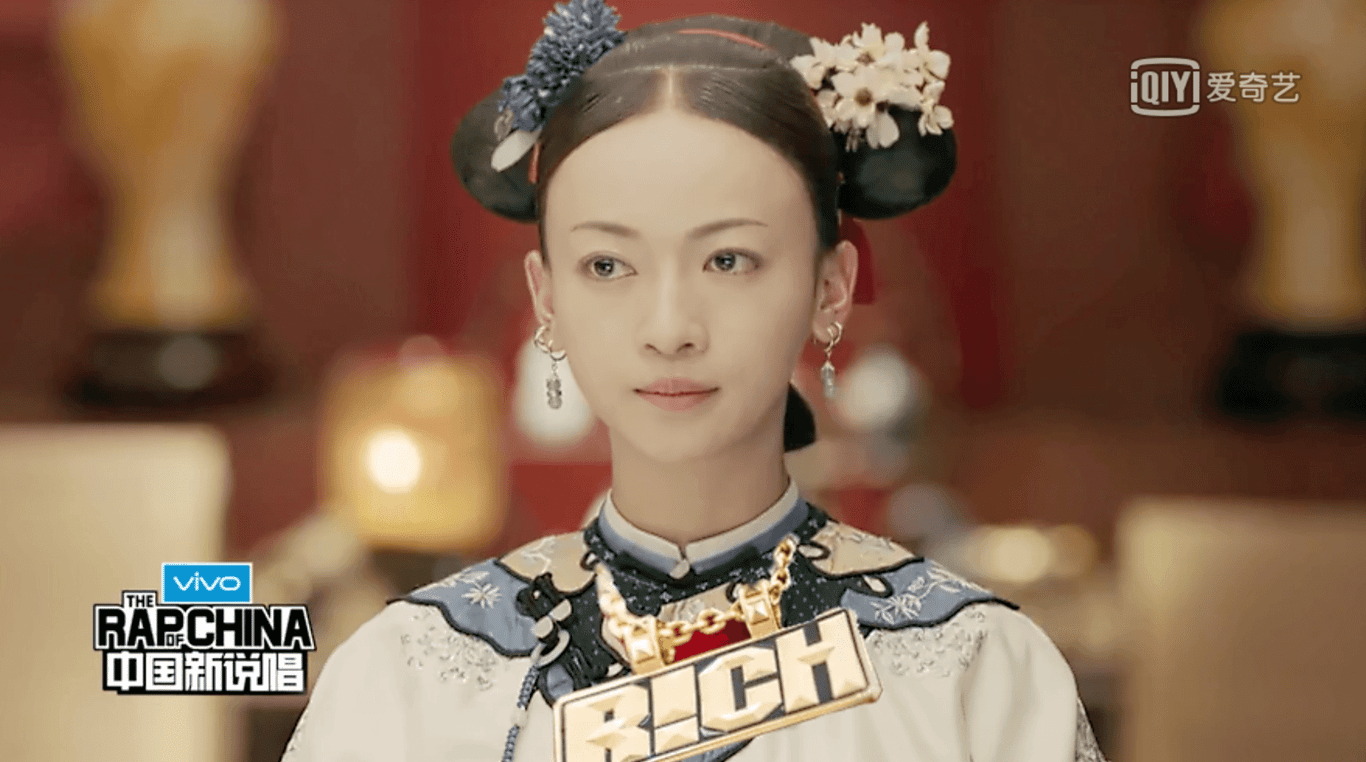

Here’s the “Yanxi Palace” x “Rap of China” Mash-up Nobody Asked ForArticle Sep 01, 2018

Here’s the “Yanxi Palace” x “Rap of China” Mash-up Nobody Asked ForArticle Sep 01, 2018

China Channels Iconic ’70s Coke Ad for Belt and Road RemixArticle Sep 12, 2018

China Channels Iconic ’70s Coke Ad for Belt and Road RemixArticle Sep 12, 2018