Only months ago, Beijing’s King of Party was a hotspot in the city’s nightlife. An impressive karaoke club that spread out over 5,500 square meters, it was known for its extravagance and its celebrity customers — Wang Sicong, one of China’s youngest billionaires, once spent 2.5 million RMB (around 350,000) in a single night there.

But a day before going back to work, the club’s 200 staff members learnt that their employer was filing for bankruptcy, and they had suddenly lost their jobs. Having been forced to close during the Covid-19 outbreak, the company’s cash flow had entirely dried up.

China’s government has been broadcasting that life is getting back to normal, a message that culminated in Wuhan — the city at the epicenter of the outbreak — officially reopening on April 8.

Related:

After 76 Days, Wuhan Emerges from LockdownThe city that has become synonymous with the novel coronavirus outbreak tentatively reopensArticle Apr 08, 2020

After 76 Days, Wuhan Emerges from LockdownThe city that has become synonymous with the novel coronavirus outbreak tentatively reopensArticle Apr 08, 2020

But for many, the aftershock of Covid-19 is only just beginning.

According to a survey released in March by recruitment service Zhaopin, only 40% of the more than 7,000 respondents said their companies had fully resumed business; 25% had lost their jobs altogether. More than 460,000 Chinese firms have closed permanently in the year’s first quarter. Data from the National Bureau of Statistics shows that unemployment jumped to an all-time high of 6.2% in February, almost doubling the 3.6% yearly average in 2019. And within the first two months of 2020, over 5 million Chinese suddenly found themselves out of work.

With the exception of those that provided vital services during Covid-19 — food delivery and remote work apps, to name some — big and small businesses alike have had to weather slow cash flow and little relief from bills. Whether choosing to wait, act, or adapt — with varying degrees of support from the state — Chinese citizens are coping with lost jobs in a number of different ways.

Waiting for Change

As a sales representative for Chinese tours in the United Arab Emirates, Jin Xi was thrilled to have hit her targets for Lunar New Year in late January. However, as the situation escalated and Covid-19 saturated the news, she had to cancel her orders one by one. “I had several sleepless nights,” she recalls. “I felt like I had prepared a table of delicacies, but nobody wanted them anymore. I had to pour everything into the trash bin.” The tourism industry lost a total of 540 billion RMB (around 76.5 billion USD) as people cancelled their travel plans for the Chinese New Year.

Jin comforted herself in that she could finally enjoy a quiet holiday without endless calls from clients, and that business would pick up again soon. But the long, deafening silence that followed would gradually deflate her. On March 19, UAE announced they had stopped issuing visas on arrival, and her company told her to remain at home until further notice. Once a thriving sector, tourism would soon become one of the most devastated industries; by the end of March, 11,268 tourism companies like hers had shuttered.

“I started thinking maybe I should switch jobs,” she says. “But what else can I do?” After working tirelessly in tourism for years, it was the first time she started to envision a different future. As she waits for the situation to pass, she’s decided to take up courses in graphic design and Japanese. Her colleagues at her job are not staying idle, either. “Now my WeChat feed is full of people selling everything from wild honey to bamboo shoots,” she laughs. “It’s like a farmer’s market.”

Related:

Watch: How China’s Army of Apps Helped People Through Coronavirus IsolationInternet use rocketed in China during Covid-19 lockdowns. But what were people actually up to?Article Apr 08, 2020

Watch: How China’s Army of Apps Helped People Through Coronavirus IsolationInternet use rocketed in China during Covid-19 lockdowns. But what were people actually up to?Article Apr 08, 2020

According to the China Performance Industry Association, over 20,000 shows were cancelled or postponed in the first three months of 2020, resulting in a direct box office loss of 2.4 billion RMB (around 340 million USD). As a lighting technician for such shows, Yang Yang has had zero income in the past two months, but his rent in Shanghai went up.

Once Shanghai’s government announced that it would waive February and March rent for small- and medium-sized companies, more than 14,000 applied, resulting in a total of 1.2 billion RMB (around 170 million USD) in rent being relinquished. But since this isn’t enforced for private properties, the question of waiving rent is subject solely to landlords’ goodwill — which has led to many conflicts between landlords and renters.

Yang has been preparing himself for further study, as he aspires to go “from a lighting technician to an artist.” Yet faced with his current reality, he admits:

“There are many freelancers like me in the theater industry. I know some have started delivering food. I will join them, if there is no income coming in the next months.”

Hitting the Road

Yang is far from the only one who has considered food delivery. As mainland Chinese order 2 billion RMB’s worth (around 280 million USD) of meals every day via apps, there has always been a steady demand for waimai xiaoge (外卖小哥) or food delivery drivers. And though interprovincial shipping was halted for a period of time, delivery drivers were operating on the frontlines, delivering groceries and takeout to people in their homes.

From late January, delivery app Meituan added 336,000 new drivers over the following two months. The app disclosed that 37% of new riders had previously had jobs in the service industry, at places like restaurants, fitness clubs, and hair salons.

Related:

Meituan: The “One-Stop Super App” That’s Hungry for ExpansionArticle Jul 04, 2018

Meituan: The “One-Stop Super App” That’s Hungry for ExpansionArticle Jul 04, 2018

One such recruit, a driver named Wei, used to be a fitness instructor in a Beijing gym. His gym had planned to remain open throughout Chinese New Year, and persuaded him to stay and earn triple his income. Unfortunately, this plan was quickly awash. He finally decided to take up delivery driving on Valentine’s Day. “I am a bit worried about my finances,” he told Chinese tech media platform 36Kr. “Plus, lying in bed all day also makes me lose muscle.”

Others like Wei took up the job not only for income or to get in shape, but also for a sense of purpose after an extended period of unemployment. Xiaowei, who lives in Beijing with her parents, found out her contract with an exhibition company was not being renewed after the outbreak.

“Frankly speaking, this virus helped cover up my unemployed status, as everyone was at home,” she says.

“But since people are now going back to work, I told my family that my company would start up in May. Hopefully I can find something by then.

“Not having a job really takes a toll on your self-esteem. Sometimes I feel like a loser for being unemployed and single at this age.” In the interim, Xiaowei has since decided to try delivery, as riding through the city to deliver food makes her feel better.

Related:

Chinese Bars are Delivering Drinks to Stay Afloat Through Coronavirus QuarantineArticle Feb 19, 2020

Chinese Bars are Delivering Drinks to Stay Afloat Through Coronavirus QuarantineArticle Feb 19, 2020

Of the hundreds of thousands of drivers that power delivery services like Meituan and Ele.me, less than 10% of drivers are female, according to data from Meituan (link in Chinese). Though anyone with an electric bicycle and a health certificate can apply to become a driver within minutes via these apps, the job is not easy. Strength and stamina are required to deliver food within the guaranteed 30 minutes, and that’s just in normal weather conditions.

“Delivering [food] keeps me on the go, so I don’t have time for negative thinking,” Xiaowei says. “Once I delivered a week’s groceries to an old grandmother, who told me she had been eating the same noodles for two days straight. I felt needed.”

Shared Economy 2.0

Not only are individuals adapting to a new occupation — but in some cases, their employers are doing it for them. As online grocery shopping became the new norm, Alibaba’s Freshippo — known as Hema (盒马) to domestic customers — saw a 220% increase in online orders. To offset its shortage of staff, Freshippo launched a scheme called “employee sharing” — that is, borrowing employees from businesses hit hardest by Covid-19.

This is particularly relevant for restaurants, as the industry lost 500 billion RMB (around 70 billion USD) once all reunion dinners were cancelled during the usually busy Lunar New Year period, and were then asked to close for weeks on end. Over 13,000 restaurants shut down in the first two months, and those that survived are still struggling to overcome drying cash flow and rising bills. One national restaurant chain, Xibei Oat Noodle, said that its 20,000 employees had lost their jobs only a week into February, as its 400 restaurants were closed and their cash flow, they claimed, could last only three months.

Xibei responded to the scheme by sending 1,000 people to pack groceries at Freshippo. In total, more than 5,000 workers from over 40 businesses — including restaurants, hotels and cinemas — participated in the scheme. Freshippo has since announced that it plans to launch an employee sharing platform in April to promote the model across China.

Related:

This Online Art Exhibition is Exploring the Emotional Impact of Covid-19Dive into an online art exhibition featuring artists from across China and the globeArticle Apr 01, 2020

This Online Art Exhibition is Exploring the Emotional Impact of Covid-19Dive into an online art exhibition featuring artists from across China and the globeArticle Apr 01, 2020

State Aid

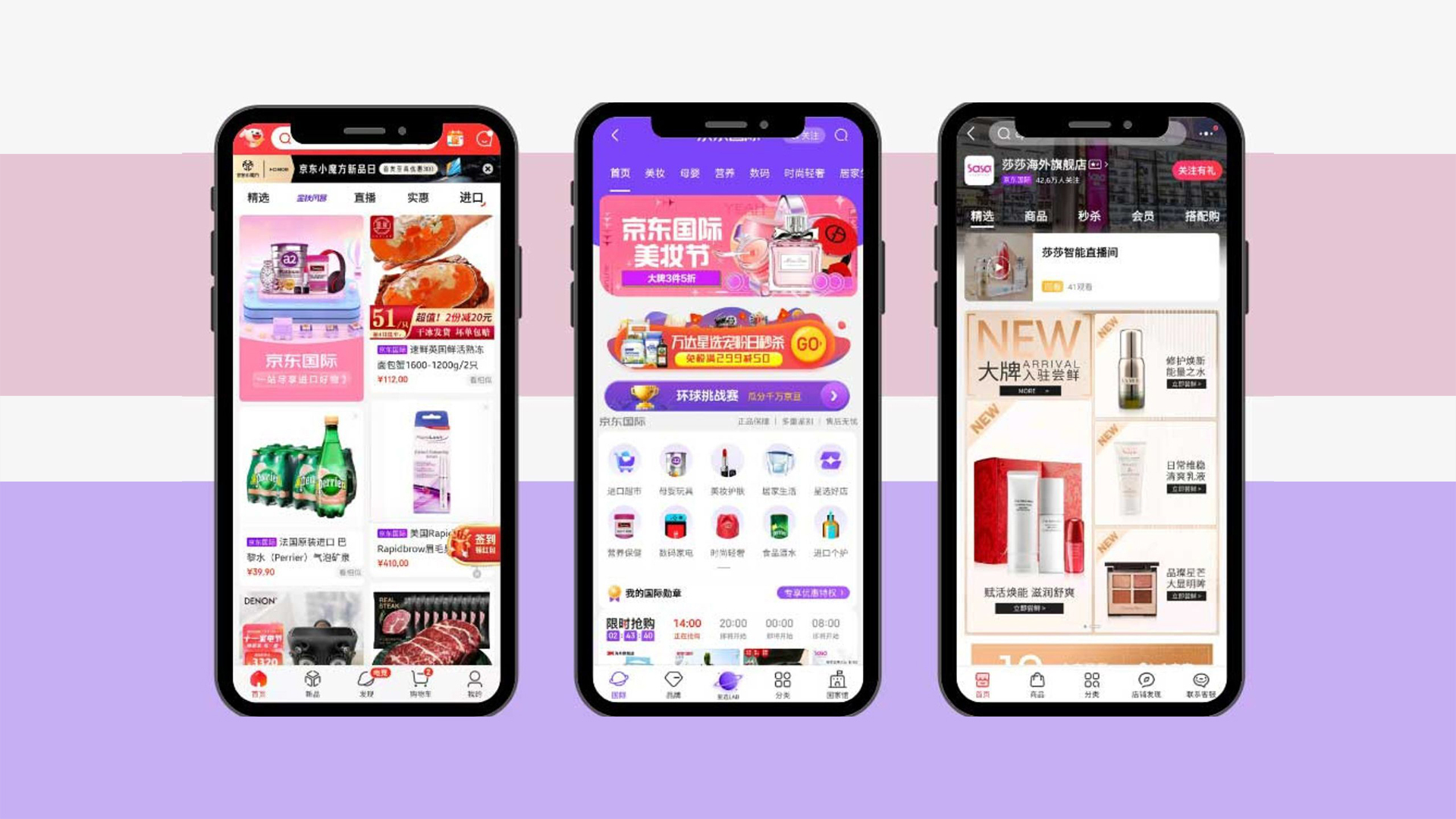

On multiple levels, China’s government seems to be advocating for technology in fighting job loss almost as much as fighting the virus itself. Faced with long queues at service centers, the central government allowed people to apply for unemployment benefits using their mobile phones as of March 31.

In addition, China’s State Council also urged digital platforms to offer more flexible services to look for jobs. Alipay — one of China’s leading digital payment platforms — launched several recruitment “mini programs” (essentially apps within apps) in response that enabled over 1.64 million people to land jobs, according to data from the company (link in Chinese).

Over 10,000 migrant workers have reportedly found work through one such mini program called “Kuaima Zhaogong” (快马找工). In China, migrant workers typically get jobs through word of mouth or through job agents, or in some cases, by gathering and waiting for opportunities to appear. The platform promises to provide more readily available, accessible options, and offers a free shuttle bus service that takes migrant workers to job interviews if needed. Jobs acquired through the Kuaima service also allow for daily wages, as opposed to monthly pay, since some of the workers currently don’t have enough to last them through the month.

But naturally, those who land jobs must be carrying a green version of Alipay’s health QR code — a widely used digital “traffic light” during the Covid-19 period that effectively bars or allows a person’s entry onto transportation and into restaurants, public spaces and even apartment complexes.

Related:

6 Ways China Has Turned to Tech to Tackle the CoronavirusAttempted technological solutions have come to the fore as China grapples with 2019-nCoVArticle Feb 05, 2020

6 Ways China Has Turned to Tech to Tackle the CoronavirusAttempted technological solutions have come to the fore as China grapples with 2019-nCoVArticle Feb 05, 2020

Local governments are also promising to “go Dutch” with companies through monetary incentives aimed at keeping people employed. Shanghai, for example, announced it would return half of unemployment insurance collected last year to over 140,000 companies that keep their workforce, reducing their labor cost by 2.6 billion RMB. Guangdong province meanwhile has rolled out a reward system offering companies 5,000RMB for recruiting someone who has been out of work for over six months.

Moreover, 17 provinces have given away over 5 billion digital consumer coupons via Alipay, the city’s official WeChat account, or city-specific apps, which can then be spent on restaurants, cinemas, theaters, and attractions, in hopes of stimulating the local economy.

While the above initiatives are already in effect, these consumer coupons have proven to be the most immediate. According to the Hangzhou Bureau of Commerce, within 11 days of distributing the first round of coupons, 200 million RMB worth of coupons were used, driving total consumer spending up by 2.2 billion RMB.

The Graduates

One of the hardest hit demographics will undoubtedly be university graduates that are now seeking jobs for the first time, who have to compete with these additional five million jobseekers in a struggling economy. China’s government rolled out measures in response to help the 8.74 million university students who will graduate this year.

Related:

As Relations Deteriorate, Chinese Students Weigh The Cost of US EducationJust how much, figuratively and literally, do today’s Chinese international students value an American education?Article Jan 10, 2019

As Relations Deteriorate, Chinese Students Weigh The Cost of US EducationJust how much, figuratively and literally, do today’s Chinese international students value an American education?Article Jan 10, 2019

Graduate school enrollment will increase by 189,000, to offer students a buffer period and to better their chances of employment two to three years down the line. The government has also urged state enterprises to shoulder social responsibility and increase their headcount for graduates. Chinese gas company Sinopec was among the first to respond, pledging to add 3,500 new employees to its 2020 campus recruitment plan. The government has also said it will strive to absorb 20% more graduates through its civil service exams.

Li Li, a fourth year student at Ningbo University, is trying to remain positive despite the bleak job forecast. She has already started to search for jobs, but says she is not the only one looking; everyone in her family is checking local sources and asking people in their personal networks on her behalf.

“Some say this graduation season will be hell for us. But I am not afraid,” she says. “I wish to take gown photos with friends, hug them goodbye, and wish them good luck.”