The first time I heard of Eric Zhao (aka Zhao Zhigong) was on the podcast SL, hosted by Wes Chen (co-founder of long-running Chinese hip hop radio program The Park) this past March. I quickly realized that I’d already read Zhao’s legal explanations before, on Weibo. One of the only music-industry-focused lawyers in China active on social media, Zhao never holds anything back, always readily offering professionally detailed information. He’s a hard person to miss for anyone who cares about copyright issues in China’s music industry.

What made Eric Zhao — an international economics law major who graduated from City University of Hong Kong, and is now partner at a law firm — want to become involved with the chaotic and ambiguous frontier of China’s music industry? It’s likely because of his second occupation, arguably a more enjoyable one: a beatmaker, producer, and lifelong music digger.

Born and raised in Shanghai, Zhao was exposed to different kinds of music as a child thanks to the cassette tapes that his father, who worked for a foreign company, brought back home, or that Zhao’s friends brought from overseas. After listening to Brian McKnight on the radio by chance, he started exploring the R&B section at stores selling dakou — semi-illicit imports from Western music labels — when he was still a middle school student. After a few years, the internet opened up a rabbit hole to young Zhao, allowing him to dig out music from before the ‘90s, along with a treasure trove of other titles inaccessible during the dakou era.

Related:

Photo of the day: Dakou GenerationArticle Oct 23, 2017

Photo of the day: Dakou GenerationArticle Oct 23, 2017

Zhao started making music himself around 2008-2009, when he heard Common, the Grammy-winning jazz rapper from Chicago, and found that hip hop could incorporate jazz influences. After digging deeper to discover similar artists like Nujabes and J Dilla, Zhao began making beats under the name Posheric (he currently uses a different alias, Chatomato) and collaborating with artists like Chengdu rapper Kafe Hu.

Through music, Zhao got to know artists who had been developing their career for years. Fast forward to 2017, when iQIYI series The Rap of China brought hip hop to the mainstream overnight, and Zhao was suddenly bombarded with questions from friends and musicians — too many to answer them all individually. “One day, I just decided that I don’t want anything to do with what I’m doing now [as a financial lawyer],” he tells RADII. “I won’t have any sense of achievement when I get old this way.”

Zhao was struck with the idea of writing answers to questions frequently asked by his musician friends in articles freely available to the public. After investing more and more energy into this side pursuit, he eventually transformed into a music lawyer.

Related:

The Rap of China Exposes Generational Fault Lines Among Chinese YouthArticle Sep 19, 2017

The Rap of China Exposes Generational Fault Lines Among Chinese YouthArticle Sep 19, 2017

Although Zhao’s own music has become hard to find — he’s deleted old material, and changed his ID — as a music industry lawyer, his influence has grown steadily over the last few years, as he deals with bigger cases and helps more independent Chinese musicians.

I recently had the chance to connect with Zhao for an in-depth discussion, after he finished his duties as legal director of last month’s JZ jazz festival in Shanghai. Our conversation provides a clear picture of what China’s music industry, copyright protections, musicians’ career development opportunities, and public music tastes look like through a lawyer’s and musician’s eyes, as well as what preoccupies Zhao most now, and what he anticipates for the future of the music industry in China.

Eric Zhao poses with his trusty MPC

Judiciary Authorities’ Attitude Towards Copyright Protection

RADII: JZ Festival must have been huge. How was it?

Eric Zhao (aka Zhao Zhigong): Yeah, JZ is the biggest jazz festival in China. There were three venues in Shanghai, and a franchise in Guangzhou. It’s been held for 15 years. This year, we invited some big international artists such as Lalah Hathaway, Jacob Collier, Marcus Miller, The Earth Wind & Fire Experience Featuring The Al Mckay Allstars, Jaga Jazzist, and it went pretty well. I’m really happy about it.

Other than JZ, what other projects or cases have you been working on recently?

The current ongoing case is [Beijing-based audio services company] V.Fine’s copyright infringement suit against social media video content creator Bigger Yan Jiu Suo, whose team is affiliated with the biggest MCN [multi-channel network] in China, [Papi Jiang‘s] Papitube.

It’s being viewed as the biggest infringement case within the Chinese MCN space. A video creator illegally used [Japanese duo] Lullatone’s track “Walking On The Sidewalk,” which V.Fine holds publishing rights to as an agent, and we’ve won the first trial. But according to the judge’s decision, the damage compensation was just 7,000RMB [around 1,000 USD], so we’re filing a petition now for a second instance.

Related:

Social Network Douban Music Announces Major Merger, New Funding RoundArticle Apr 06, 2018

Social Network Douban Music Announces Major Merger, New Funding RoundArticle Apr 06, 2018

Why is the compensation so small? Is it just a judicial decision, or is there a lack of legislative support?

It’s more about the judicature. Our law supports up to 500,000RMB [about 70,000USD] in damages, but in general, the amount of compensation in real cases is low, even for successful musicians. And this is the current environment for domestic music. This is why everyone feels reluctant to speak up when they are infringed upon, because basically everyone knows that the compensation will be low. It takes a great amount of time and energy, material resources and manpower, and a lot of things need to be done, but in the end the compensation can not cover costs.

“Everyone feels reluctant to speak up when they are infringed upon, because basically everyone knows that the compensation will be low”

Why does it work like this?

I think it is an attitude towards intellectual property protection. Our system does not encourage these kinds of punitive damages, but rather [favors] rational compensation. A punitive mechanism providing better protection [for creators] has not yet been established. If the infringers pay 10 million RMB, no one will dare to infringe, because they will lose everything. But now it’s more like, “if infringement only results in a 7,000RMB fine, then I might as well prepare that money and go infringe.” The system is not conducive to improving the overall environment, and therefore no one is speaking up.

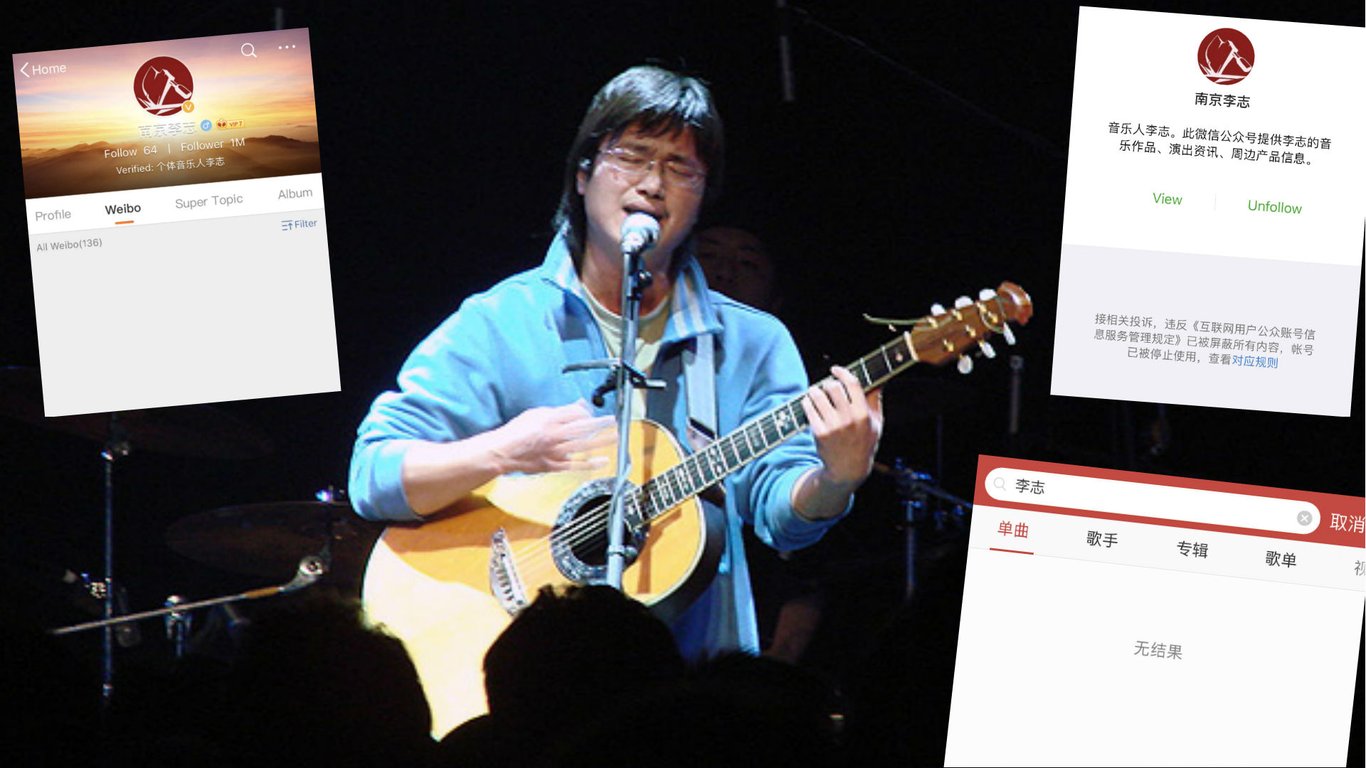

What about Li Zhi’s cases where he actively pursued some high profile copyright infringements? They’ve attracted quite a bit of public attention — but did they make any difference?

Actually, his final amount of compensation was pretty high, although many people think it was still low. The amount of compensation he sued for was 3 million RMB [about 425,000USD], but the actual amount turned out to be 200,000RMB — still very high [for China], especially compared with our results.

Related:

Where is Li Zhi? Outspoken Folk Musician Seemingly Scrubbed from InternetLi Zhi has seemingly had his profiles deleted from major online platforms just months after a planned tour was abruptly cancelled in mysterious circumstancesArticle Apr 14, 2019

Where is Li Zhi? Outspoken Folk Musician Seemingly Scrubbed from InternetLi Zhi has seemingly had his profiles deleted from major online platforms just months after a planned tour was abruptly cancelled in mysterious circumstancesArticle Apr 14, 2019

Are you, as a lawyer, optimistic about making a difference within the current environment?

I think there’s still possibility. I love music, and I know the music industry pretty well. It’s getting a lot better now, compared to the time when I was making music. It was like a primal chaos then. Although it’s still rather dark now, we can also see some light. There are definitely more people who care about and discuss copyright now, which is great progress. There was no one who cared about or understood it before.

Was there a specific turning point? I know the authorities went hard on music copyright issues around 2015 or 2016. Is it necessarily a top-down process?

Yeah, it was around that time. If we want to change the overall environment, this top-down path would be the most efficient way to solve the problem. The other way around, however, needs to be nourished by culture and the investment of time, which will take a while.

An Hourglass-Shaped Industry

At a recent panel in Shanghai organized by Eating Music, you said that the music industry in China is like an hourglass. Can you elaborate on that concept?

There is not a so-called “middle class” in the music industry. There are only the rich and the poor.

Zhao Zhigong (center) participates in a panel talk with Eating Music’s Voision Xi (left), RAN Music’s Shen Lijia (second from left), and RADII editors Jake Newby and Josh Feola (right)

Why is it shaped like this? Are there any missing parts in the industry chain?

If we’re talking about commercial music, musicians have to make their works into a commodity that they can benefit from. First of all, music should have artistic merit; it should earn profit secondarily. Only in this way can artists be motivated to create. But this is what we lack here, resulting in a situation where people who have resources seize all of the resources, and occupy the top of the hourglass. They become the artists who attract the most traffic, the singers who get the most resources, and sign with the biggest record labels.

In the middle, good music is not being promoted, and if the musicians are not signed to major labels, they don’t make money. In the end, they just perish.

At the bottom, there are newcomers and artists who are not willing to be commercialized, and just want to make what they want to make. Some of them are supposed to be in the middle [of the hourglass], but it wouldn’t be better for them to be in the middle, so they’d rather just stay at the bottom.

Are there any record labels on this top tier in China?

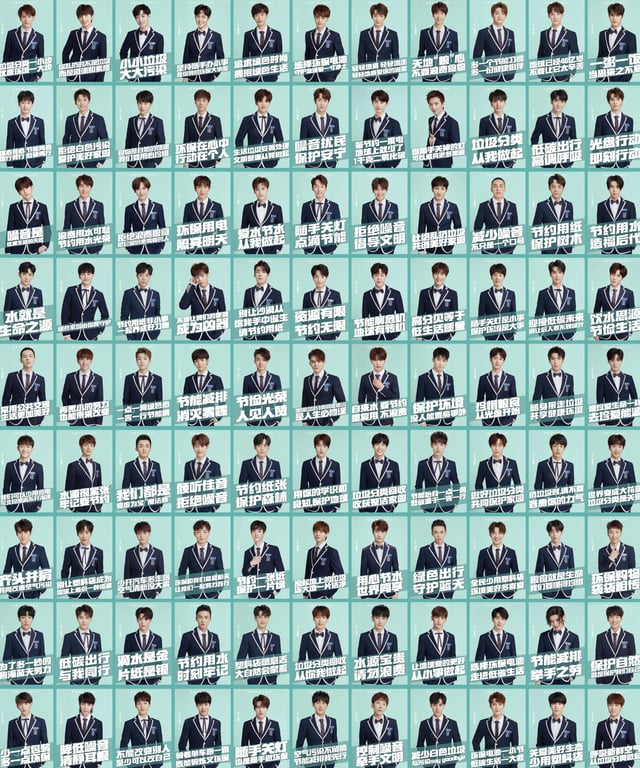

I think there are only some entertainment companies on the top. As top-tier record labels, they should be doing a great job at combining business and art. If you only value business, then I think you’re just an entertainment company. Think of the agents behind the most popular idol groups — they are entertainment companies at the top.

Related:

The Search for China’s Next Big Boy Band is Emphasizing “Social Responsibility” Over SexinessAs China’s reality-show-pop-music industrial complex churns on, can iQIYI repeat the hype it created around last year’s readymade boy band NINE PERCENT?Article Jan 29, 2019

The Search for China’s Next Big Boy Band is Emphasizing “Social Responsibility” Over SexinessAs China’s reality-show-pop-music industrial complex churns on, can iQIYI repeat the hype it created around last year’s readymade boy band NINE PERCENT?Article Jan 29, 2019

What is the “middle class” in the global music industry?

Those good independent labels, who may be bought by major record companies, but still have a large enough room to exist. Many jazz labels, like Prestige Records, used to be independent. They did a lot of classics before they were bought by the majors.

Xi’an rap crew HHH and underground freestyle battle series 8 Mile both recently established their own brands, and developed their own music streaming platforms. Do you think they can make a difference?

They are still too small. I think the best reference is American sports associations. They are scientific mechanisms, consisting of middle school leagues, high school leagues, college leagues, and minor leagues, so that athletes can level up step by step until they hit the biggest stage, professional leagues. But now everyone wants to jump straight to the NBA, which is impossible. HHH cannot be the NBA, neither can anyone else. We don’t have a system or the proper channels. There is no draft in our “NBA” — instead, we just see someone on the street who’s not too bad, and then sign them on the spot. That person jumps to the top of the hourglass directly from the bottom. It’s not right.

Related:

Chinese Rap Wrap: The HHH Era Ends with a Shocking, Livestreamed ScandalMC Bei Bei of Xi’an crew HHH/GDLF Music self-mutilates live on the internet, shocking fans; meanwhile Taiwan OG MC Hotdog opens fire on the show he judgesArticle Aug 07, 2019

Chinese Rap Wrap: The HHH Era Ends with a Shocking, Livestreamed ScandalMC Bei Bei of Xi’an crew HHH/GDLF Music self-mutilates live on the internet, shocking fans; meanwhile Taiwan OG MC Hotdog opens fire on the show he judgesArticle Aug 07, 2019

What is the ideal mechanism, in your mind?

On the very top, it must be the artists. Then the good pop artists. Then the famous indie musicians. Then fledgling musicians. At the bottom are the students who just graduated from music schools, and music educators. Between all of them, there are channels and a system to ensure that they can level up step by step. There may be a genius like Jacob Collier, who enters the “NBA” at the age of 11. But he is one-of-a-kind. Most of us have a normal path, from middle school to college, before finally entering the pros.

Eric Zhao with Jacob Collier at last month’s JZ Festival in Shanghai

I like using basketball as an example, because I used to train on a basketball team. It’s like if someone’s as good as Kobe Bryant, but he’s just playing pick-up games downstairs from your apartment. Good musicians just do music at home now; there is no good company or platform to help them. It’s sad that Kobe-level talents are playing with someone who just learned to play basketball. They should be separated into different levels, but it’s just chaotic now.

The top and the bottom can’t find each other?

Or there is not a “top.” Because the entertainment companies that we have now are not the NBA, we just have the CBA.

It’s like if someone’s as good as Kobe Bryant, but he’s just playing pick-up games downstairs from your apartment. Good musicians just do music at home now; there is no good company or platform to help them

When I was on a music industry panel at Midem in Cannes a few months back, I found that the global music industry works quite differently. There are professionals for each link of the industry chain, and most of them have years or decades of experience. It seems that Chinese companies, record labels and streaming platforms tend to do everything on their own. And we don’t have specific division as an industry chain.

Yeah, just like, “we do music.” Shen Lijia [manager of Beijing label Ran Music] said on the Eating Music panel I took part in that there are a lot of PR or A&R institutions [outside of China], and big-shot professionals who have top promotional resources. You can pay them for promotion on their channels, which could be radio programs, podcasts, or something else. It’s like a seed stage for a startup, and if your music is good enough, it could go viral after this kind of exposure. We don’t have these kinds of incubators in China. And this is the hardest stage for an independent musician.

To make it here, a musician needs to skip the seed stage and go straight to the mature stage — such as variety shows [like Rap of China]. It’s back to the shape of hourglass that we talked about, from the bottom to the top.

Where are the Opportunities for Musicians?

What do you think of these variety shows? Have they had any impact on the music industry, positively or negatively?

It’s hard to say if it’s positive or negative, but they have definitely promoted the music, and even the culture behind it, in a very short time. After the Rap of China season 1, hip hop when from 20% to 90% [in terms of public recognition]. But quite a lot of people were not ready for it. It may be a bit like the situation when some luxury brands entered China ten years ago. Everyone wanted to buy Louis Vuitton, but they didn’t even know which country it came from or how to pronounce the brand name. Now music culture is a bit like that.

What about the musicians? What impact do the one-year contracts that they sign with streaming platform and Rap of China producer iQIYI have on the rappers?

There are similar contracts in any show of this nature, but we cannot say that is unfair. Because it’s an exchange of equal values — the platform offers the artist an opportunity for exposure and popularity, and in return, the artist gives them a corresponding share [through their performance or appearance], which is reasonable.

However, at the end of the day, it really depends on how good the rappers are, and how far they can advance on the show. There are just so many terms in the contract that you need to negotiate and speak for yourself, which might cause problems.

Quite a few musicians have consulted me about it. One signed the contract, but just passed through the first round of the show, and departed without any shots of him being featured in the episodes that aired. Since he’d signed the contract, he had to be restrained from other opportunities for a year as well. I felt really bad for him, because he didn’t know the contract better and was unable to negotiate. Only if you win the championship is it a win-win.

Related:

4 Fire Solo Debuts From the Rap of China Freshman ClassArticle Oct 12, 2017

4 Fire Solo Debuts From the Rap of China Freshman ClassArticle Oct 12, 2017

What about signing with Modern Sky? They started as an indie label in the ’90s, but have grown into a massive chain involving multiple sub-labels and an international music festival brand. Most of the rappers or indie bands who “make it” in the Chinese music industry end up signing with them. They must be at the top of the hourglass, I assume?

They are at the top, but if you want to reach the top in the industry, all you can do is sign with them. And I believe anyone who has read Modern Sky’s contracts — whether or not they have any legal knowledge — will see that there’s something wrong. No one has ever told me that their contract is reasonable, that it’s a model we should recommend to friends. But they’re in a dominant position. There is no other option. There’s no room to say no, and turn to another company. Your only choice is to just stay at the bottom. So some artists think, “I’d rather go to Modern Sky, at least it’s a way upward.”

Some rappers have established their own labels recently. Is that a viable alternative?

Yes, some of them have developed well. Like my friends J-Fever and Jah Jah Way [In3, Purple Soul], they haven’t signed with any labels, but rather built their own path. I think they have real freedom.

Related:

Chinese Rap Wrap: Key NG Wins “Rap of China” S03 as Kris Wu Launches Hip Hop LabelWith Netflix launching a Cardi B-led hip hop talent show next month, iQIYI’s game-changing rap contest wraps its third seasonArticle Sep 05, 2019

Chinese Rap Wrap: Key NG Wins “Rap of China” S03 as Kris Wu Launches Hip Hop LabelWith Netflix launching a Cardi B-led hip hop talent show next month, iQIYI’s game-changing rap contest wraps its third seasonArticle Sep 05, 2019

Streaming platforms — like NetEase or Tencent-owned platforms — have signed a lot of musicians, too. Is this a good deal for the musicians?

If you sign an exclusive contract with a streaming platform, it can act like an agent, and help promote your music. But from my perspective, the best choice is just to make your own music. When the music is good, there will be opportunities. To be frank, some music is not good enough, and shouldn’t be released. Why aren’t you popular? Maybe because your music is not good enough, rather than your talent is going unrecognized. This is a misunderstanding that some independent musicians have.

So you’re saying that in the internet era, good music will never be buried?

There are two aspects to this. First, your music must be good; second, you need a good agent to manage everything for you. You need someone helpful in terms of business, someone reliable and trustworthy, instead of going straight to the platforms or companies. This agent could be helping 100 artists and playing different roles, and most of the time what they do is more like a consultancy service. They don’t necessarily go to every performance, but give you necessary advice.

Like some kind of independent agent?

I don’t think it should be called an “agent.” It’s more like an adviser, who does it all for the good of the artist, rather than any other purpose. It’s not about making money, but offering good opportunities.

That sounds like a pretty high requirement.

It is. I can do it, because I can earn a living on my own. If someone does it full-time, the income might not be stable. That said, if you can give advice and offer resources, you can’t be someone who cannot feed yourself. I hope more people will join us, like people from major labels, Universal or Tencent Music — when you leave the position on the inside [of these companies], you can do something for public benefit. Only if the industry as a whole gets better, will everyone advance.

Related:

China Explained: How Tencent Came to Dominate Music Streaming in ChinaWith strategic investments in rivals and rumored bids for Universal in the offing, Tencent is making some big moves on China’s music streaming sceneArticle Mar 11, 2019

China Explained: How Tencent Came to Dominate Music Streaming in ChinaWith strategic investments in rivals and rumored bids for Universal in the offing, Tencent is making some big moves on China’s music streaming sceneArticle Mar 11, 2019

Public Taste and Sample Diggers

I feel that there has been more discussion about plagiarism on social media this year than in previous years. Do you feel the same? Does this mean that people’s awareness around copyright issues is increasing?

My personal perspective is that it’s a lot easier to spread music now. Back in the ‘80s, we had to ask family friends overseas to bring cassette tapes and CDs back to China, so no one would even have known if something was plagiarized. Now, listening to music is so convenient, so everyone has heard lots of music.

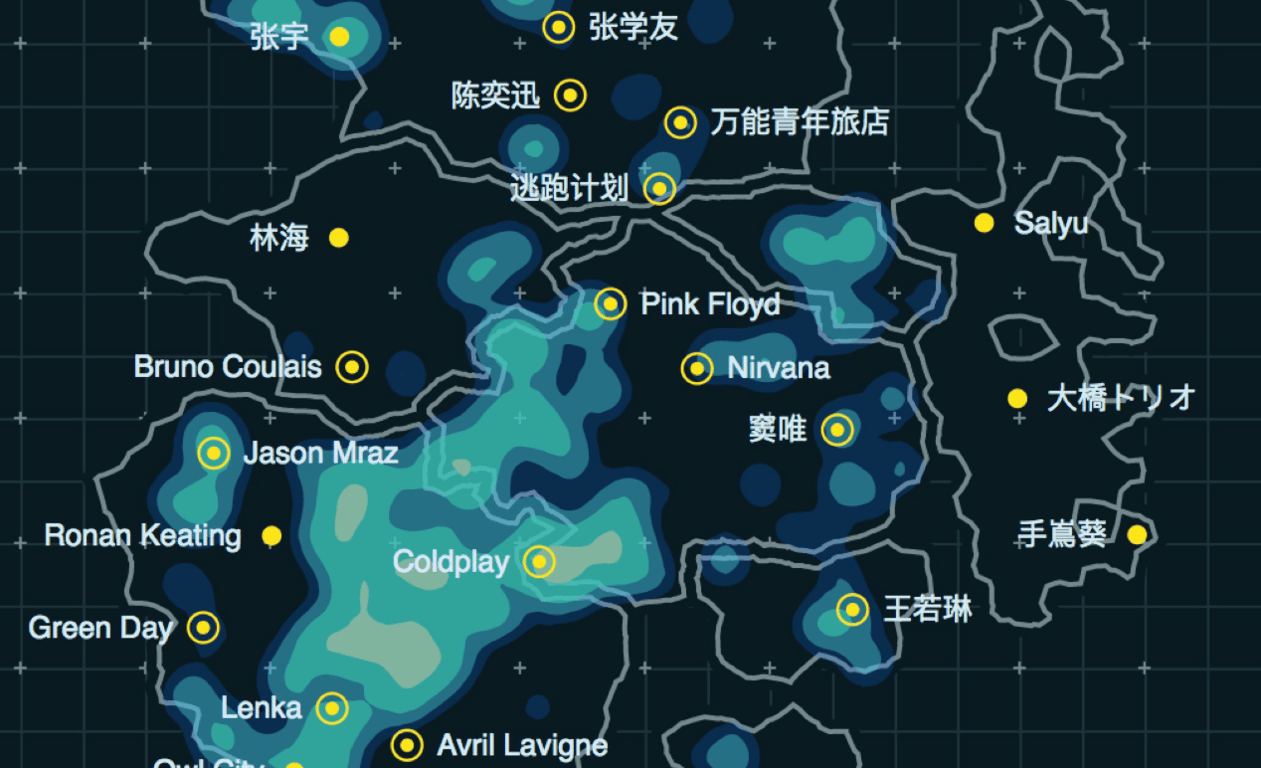

I used to collect vinyl records from the ‘70s and ‘80s, and dug into sampling. I might have been seen as an expert back then, but now I feel like everyone is an expert. You go to some foreign websites and discover some rare samples, then you find that it has been played 3 million times — it might have just been played like 63 times before, but now it’s 3 million. And you can often find some famous experts in the comments on the streaming platforms as well.

In the ‘80s, we had to ask family friends overseas to bring cassette tapes and CDs back to China, so no one would even know if something was plagiarized

Music digging is not some [obscure hobby] nowadays, so I guess this is why a lot more discussions about plagiarism have appeared.

What do you think of music on short-video platforms like Kuaishou and Douyin/TikTok? Are they reaching a different group of listeners?

That’s about a mass, public aesthetic standard for music, which is at a basic level — not high and not low. And there’s nothing wrong with that. It exists in every country, no matter how developed the music industry is. And honestly, no one is better than anyone else, you cannot ask everyone to love music and spend as much time learning about it as you do.

I’ve talked with many friends who have concluded that Americans’ mainstream taste in music is not better, and may be worse [than in China]. The upper part of the industry, however, decides how developed the industry is. We have a long way to go, when comparing our professionals’ expertise, taste, aesthetics, and anything else with [our overseas music industry counterparts].

Related:

TikTok Drops an Album, Vows to “Help Musicians Be Heard”With the release of its first music compilation, is short video platform TikTok setting its sights on China’s music industry?Article Jan 23, 2019

TikTok Drops an Album, Vows to “Help Musicians Be Heard”With the release of its first music compilation, is short video platform TikTok setting its sights on China’s music industry?Article Jan 23, 2019

So in the internet era, what can musicians, labels, and music lovers do to help build up the industry?

We need more professional music media, someone to speak up for the culture. When I was a child, I could find music magazines like Eazy or Hit Music. They introduced a lot of information about Western music, which was hard to find at the time. No one is reading these magazines now. If I want to learn about a music genre that I’m not familiar with, there are no beginner’s resources to start with. The platforms won’t tell me who they are.

It’s the same with American mainstream culture — people just care about what Kanye West is wearing. The public’s aesthetic is like the flow of water: you don’t expect it to flow upward. It depends on how it’s guided. Now all of the water just flows to Kris Wu or Cai Xukun. When I or anyone else deep in the culture industry turns on our phone, we just see that kind of feed. Before there were some experts and media to tell us where to find what we wanted to find — now people just receive and accept this feed passively.

Related:

Idol Hands: How China’s Super Fan Groups Make and Break Stars Via the Multi-Million Dollar “Fan Economy”Article Jan 07, 2019

Idol Hands: How China’s Super Fan Groups Make and Break Stars Via the Multi-Million Dollar “Fan Economy”Article Jan 07, 2019

So the public needs to be educated?

There just needs to be a channel to let music listeners find the music they want. They don’t have to like jazz, but they might like techno. They can just find good music labels and listen to more good music, instead of staying on Fox, or watching the third season of Rap of China. That’s pathetic. How many of the new hip hop fans tracked back to listen to Purple Soul? So few.

In the areas that you’re interested in, jazz or hip hop, have you ever seen any media promoting the culture and the history in the right way?

There are a lot actually, but they have never been promoted as much as they deserve. Most of the reports that people read are more about entertainment and gossip. No one writes criticism. But a lot of people from the Douban era still hang in there. What I read now is not much different from what I read a decade ago, but it’s harder to find [for a beginner]. Like there’s a WeChat account that introduces black music from the ‘70s to ‘80s called “Diggers’ Delights,” the writer of which, Shi Jing, wrote a book called Hip Hop Bible in 2007 to promote hip hop culture. Those are valuable resources, but they are not promoted. Some people may just want to wear something cool, but for the people who want to learn more about the music, its history and culture, they don’t know what to read or where to find it.

Related:

Douban FM is Fighting the Music Streaming Wars with Innovation and an Artist-First ApproachArticle May 02, 2018

Douban FM is Fighting the Music Streaming Wars with Innovation and an Artist-First ApproachArticle May 02, 2018

Building a New Chinese Music Media

I can see that you emphasize music media a lot.

I think there are big problems with the media. Of course there have always been some systematic problems, but now I mean the KOLs [“key opinion leaders” or social media influencers], they should take more responsibility. I mean the internet companies, who will have to pay back in the end. Back when they started, they attracted users through piracy, infringement, and free music they had no right to, which planted a misconception in so many people’s minds that there’s no need to pay for music. Now we need a generational effort and energy to make it right.

Back when [Chinese streaming platforms] started, they attracted users through piracy, infringement, and free music they had no right to, which planted a misconception in so many people’s minds that there’s no need to pay for music. Now we need a generational effort and energy to make it right.

Tencent Music is spending so much money on copyright legalization, it’s actually paying the debt for all of the other internet companies. If the media just report gossip, there is no culture, and the music diggers will be fewer and fewer. One day we will see the water flow into the sewer. By then, it’ll take so many more resources and so much more effort to build the culture from the top down. It just needs a little bit of cost to get it done right now, but no one is doing it.

Have the variety shows like this summer’s The Big Band promoted the culture a bit?

I think they did an OK job. It’s not really their obligation. But there could be some entry points. [Beijing band] Click#15 appeared on The Big Band, giving the show’s viewers an immediate introduction to James Brown and other funk classics. It doesn’t necessarily have to be like a textbook. Now we have some KOLs — I know them, and their rates — who write something about music, but they’re not really introducing the music itself. It’s just business.

It’s also the readers’ choice, right? To choose what to read?

People who write good content have no experience running media. They are more like independent musicians. If there are good channels, they can contribute to bigger media, and be republished by some even bigger ones. An ideal structure is shaped like a pyramid. They cannot expand their influence if they stay in a small circle, instead of being cared about and republished by major media.

Should media outlets take more responsibility?

Yes, because it’s something that we read and see every day. In this modern society, what media feeds us is essential, as are press ethics. If they don’t have [ethical content guidelines], there will be problems across the country and throughout the system, and ultimately in people’s personal relationships.

We have seen this clearly in recent years. As a music lawyer, what’s your goal in the long run?

I still want to do something to promote the culture. I hope more people will learn about music culture. They don’t have to know how to mix or adjust music tracks, but if they like a musician, they can find something else [about the music] that they want to learn about. Actually, I want to establish a decent music media platform to promote music.

I’ve been reading your articles that explain music-related legal terminology on your Weibo and WeChat accounts. Will you continue to self-publish these?

Yes, I’ve found that so many people need it. People who work in the global music industry already know it, more or less. But within our country, we can say that no one knows it, which is so weird. We have a music industry, and it’s still running. It’s like everyone is eating to survive, but we don’t really know what we’re eating. It could be made of protein from bugs. It’s time to learn how to cook a decent meal. It’s good that some institutions are working on this now.

We have a music industry, and it’s still running. It’s like everyone is eating to survive, but we don’t really know what we’re eating. It could be made of protein from bugs.

I had a meeting with an international copyright organization which consists of experienced professionals from the global music industry. They want to organize some workshops and panels in China, so they invited me to help them with it. They cannot give a speech in English directly to a Chinese audience, or people may not be interested. In fact, we have the genuine chefs here. We just need to wrap up their content a bit, making it into an internationalized Chinese cuisine. It’s up to the industry professionals, or anyone that is interested — musicians, agents, journalists.

How have these copyright workshops worked so far? What kind of problems have the musicians encountered?

I think they’ve helped a lot. They are thirsty for the knowledge, and I am always encircled after the workshop every time. No one has ever told them how to deal with these problems. It depends on what they do, so the problems and questions are totally varied. I hope the workshop will turn into an online course, and can be shared with everyone, anywhere, anytime.

—

When Eric Zhao ran into some lawyers from Memphis in 2010, their title of “entertainment lawyer,” and their day-to-day work focusing on music specifically, sowed a seed in Zhao’s mind. Today, Zhao’s work is in turn sowing many more seeds in many more minds — legally, musically, systematically.

When we talk about music, we can be talking about many things: taste, emotion, technical skill. But when it comes to a music industry, more rational and serious professionals from all areas are very much needed. Hopefully the current period of “darkness before dawn” will not last much longer, and we can soon build up an industry where musicians and music lovers can find each other and enjoy music better.