[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]It’s been a wild week for an aspiring despot.

From an anonymous New York Times Op-Ed published this week:

The erratic behavior would be more concerning if it weren’t for unsung heroes in and around the White House. Some of his aides have been cast as villains by the media. But in private, they have gone to great lengths to keep bad decisions contained to the West Wing, though they are clearly not always successful.

It may be cold comfort in this chaotic era, but Americans should know that there are adults in the room. We fully recognize what is happening. And we are trying to do what’s right even when Donald Trump won’t.

And then the tip of what is sure to be an iceberg of semi-attributed lunacy coming out in a new book by notorious Presidential scold Bob Woodward:

At a January meeting of the National Security Council, Mr. Trump asked why the United States was spending so much on the Korean Peninsula.

Defense Secretary Jim Mattis replied that the administration was trying to prevent World War III. After Mr. Trump left the room, Mr. Woodward wrote, Mr. Mattis told people that Mr. Trump understood the topic like a “fifth or sixth grader.”

In another episode, Gary D. Cohn, the former chief economic adviser to Mr. Trump, “stole” a letter from Mr. Trump’s desk that the president had planned to sign, withdrawing the United States from a trade deal with South Korea. Mr. Woodward wrote that Mr. Cohn told a colleague that he had to “protect the country.” Mr. Trump apparently never realized the letter had disappeared.

Disloyalty? Treason? The scheming of bureaucratic factions to thwart the ambitions of a mad head of state?

Here’s the thing though: Bob Woodward and the New York Times have nothing on Chinese history.

Teahouse whispers and desperate remonstrances written by an anonymous pen from within the palace walls were all in the game back in the imperial era. The system depended on the willingness of officials to occasionally stand up to the worst impulses of those they served.

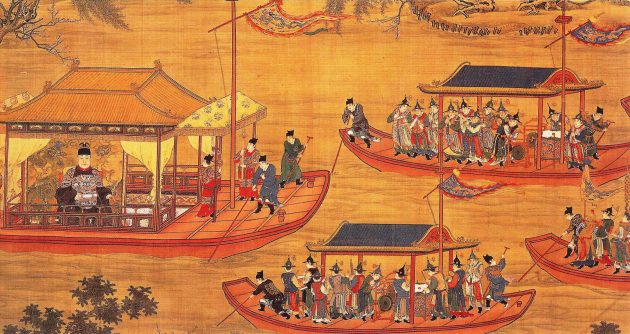

Consider the Ming Dynasty. It’s a wonder this dynasty lasted as long as it did with a roster of emperors that – with a few exceptions – hardly inspired confidence in the Son of Heaven. The Ming Dynasty once misplaced an emperor. They had another emperor unceremoniously poop himself to death after just a month in power. The Jiajing Emperor, who ruled 47 years from 1521-1567, was nearly whacked by his own harem after they reportedly tired of unusual sexual practices supposedly meant to give him everlasting vitality.

(Later he would switch to alchemical methods, many of which used mercury as a key ingredient, and that was the end of the Jiajing Emperor.)

The Jiajing Emperor [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][r. 1521-1567][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]on his royal barge. In 1538, his own consorts tried to kill him after they tired of increasingly bizarre sexual practices.

The Emperor Wan Li was the longest-reigning monarch of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

The Wanli Reign was famously bad. The compilers of the official Ming History, admittedly a group employed by the dynasty which replaced the Ming, had no trouble dating the beginning of the end of the Ming to Wanli’s reign. This even though Wanli ruled nearly a half-century before a rebel army stormed Beijing in 1644 putting a stake in the heart of the Ming Dynasty and clearing the way for the Manchus of the Qing Empire to set up shop in the Forbidden City.

The Wanli Emperor’s feckless approach to ruling an empire also inspired the title of Ray Huang’s classic 1980 study of the late Ming era: 1587: A Year of No Significance. The phrase was an audaciously apathetic description entered into the official court records during a period of Ming history which was anything but insignificant when factional disputes and political intrigue threatened to topple the already tenuous balance of power between the emperor and the officials who served him.

In an article published in 2000 in the journal T’oung Pao, historian Jie Zhao nailed the description of the Wanli Emperor’s basic approach to his job:

“Study sessions, ceremonies, memorials, and daily audiences with officials bored him…remained aloof from government affairs while insisting on his right to ultimate power.”

Sound familiar?

“We should not underestimate the importance of imperial study sessions, ceremonies, reviewing of memorials, and daily audiences. Woven together as a web of restraints, they worked to mold an emperor’s public persona as a responsible ruler and a man of dignity and compassion. These rituals exalted the emperor, but they also restrained him, trimming his rough edges and taming his tyrannical impulse as far as was possible. Above all, they pressured him to maintain a modicum of civility and self-restraint toward his subjects, especially those around him.”

What happens when an emperor (or president) not only is no longer wearing clothes but is, to pursue this particular metaphor to its logical conclusion, buck naked flaunting his exposed genitalia while pleasuring himself with the enthusiasm of an amorous priapic gibbon?

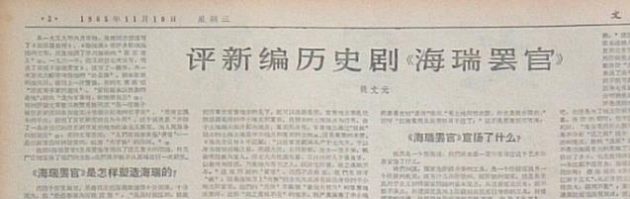

If you’re an official in the Ming Dynasty – or in the current US administration – you find ways to express your displeasure even if it’s not the wise career move. The story of Hai Rui (1514-1587), who courageously criticized the actions of the Jiajing Emperor (he of the homicidal harem and mercury poisoning) made Hai Rui the model of the upright official standing up to power. 500 years after Hai Rui’s principled stand, the play “Hai Rui Dismissed from Office” would so anger supporters of Mao Zedong who took umbrage to their Chairman being compared to a despotic lecher in need of virtuous restraint that they responded by launching the Cultural Revolution.

1965 article denouncing the play “Hai Rui Dismissed from Office” by Wu Han. The politics surrounding the play and its subject was one of the early catalysts for what became the Cultural Revolution.

During the early years of the Wanli Emperor’s reign, the government was under the thumb of the powerful Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng. The emperor was still young, and Zhang is famous for his hard-charging approach to policy and general lack of fucks to give about what other people thought about his management style. When Zhang died in 1582 however, the now young-adult emperor wasn’t keen on having any other powerful minister dictate his agenda and take all the credit.

Other members of the bureaucracy felt the same way, and the result was a series of milquetoast Grand Secretaries culminating in Shen Shixing (1535-1614). Shen approached the art of managing up like he was the riding shotgun in a human centipede. He’d screen memorials for the emperor and then expunge the emperor’s replies from the official records. Shen knew the emperor was a desperately unstable man-child but wanted no part in trying to rein in the worst tendencies of the throne. Instead, he tried to shield the emperor from the realities of his job and the world from the reality of a court in turmoil.

The result was an endless cycle of political fighting as both the emperor and Shen Shixing found themselves on the receiving end of increasingly vocal criticism from partisan officials concerned about things like “fiscal responsibility,” “imperial decorum,” and “not having a three-hundred-year-old dynasty crumble to dust on their watch.”

It’s perhaps unfair to hold the Wanli Emperor entirely responsible for the ultimate demise of the Ming. Part of the blame ought to be assessed to the Ming dynastic founder, the Hongwu Emperor (r. 1368-1398) for abolishing the office of Prime Minister and centralizing an excessive amount of power and administrative responsibility in the hands of his descendants, many of whom turned out to be idiots.

The Wanli Emperor’s descendants weren’t especially prizes either. His son was thought to have what would much later be called “Learning Skills Issues” and, unable to read documents submitted by his officials, chose instead to play at carpentry while his wet nurse and favored eunuchs ran the dynasty into the ground.

Something to remember if Donald, Jr. ever decides to try and run for office.

—

You might also like:

Sex and the (Forbidden) City: Concubine Drama “Yanxi Palace” Becomes Smash Hit in the #MeToo EraArticle Aug 27, 2018

Sex and the (Forbidden) City: Concubine Drama “Yanxi Palace” Becomes Smash Hit in the #MeToo EraArticle Aug 27, 2018

The United States and China: Too Close for ComfortArticle May 23, 2018

The United States and China: Too Close for ComfortArticle May 23, 2018