“Education should not shackle us,” claimed a college graduate identified only as Ms. Huang in a recent segment on BRTV, a Chinese state-owned network in Beijing.

Four years after graduating from the prestigious Zhengzhou University with a degree in international economics and trade, Huang made a surprising decision last August and started a part-waste collection, part-scrap yard business as she grew bored with moving from one job to another and the repetitive nature of office life.

Instead of rushing to a cubicle in one of the city’s high-rises every morning, she would go to customers’ apartments to pick up recyclable garbage, from cardboard boxes and plastic bottles to old televisions and washing machines.

The waste collector profession has long existed in China but has always been considered a blue-collar job done primarily by people without an education or professional training.

Her statement was an apparent rebuttal to the so-called ‘Kong Yiji mindset’ (孔乙己文学), a term used to refer to college graduates who consider themselves above manual labor.

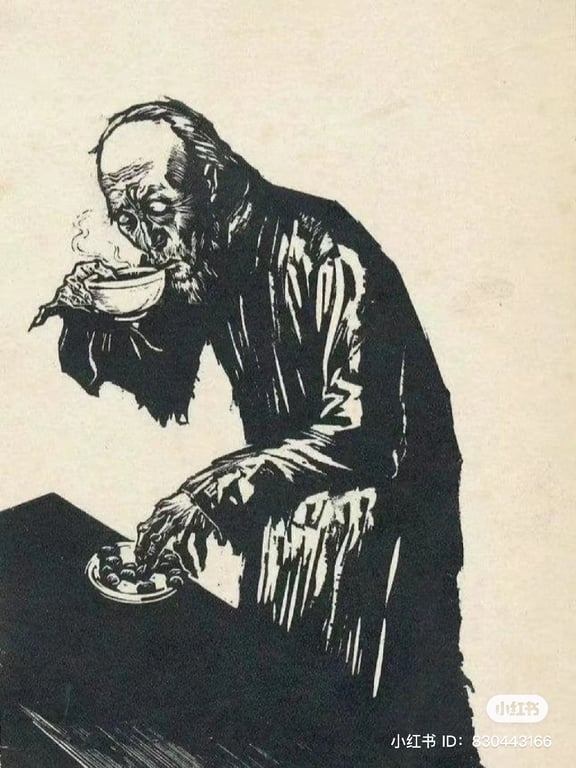

The new term is taken from a 1919 short story by Lu Xun, one of the most influential figures in modern Chinese literature, about a self-important scholar named Kong Yiji.

In mid-March, the story returned to the internet’s collective imagination after one person wrote, “Education is not a stepping stone, but a high platform that I can’t get off, and it’s also a long gown (a type of clothing worn mostly by scholars or government officials during Qing Dynasty) that Kong Yiji can’t take off.”

To Huang, though, there are benefits to getting off the “high platform” of education. “So far, my monthly income can exceed the five-figure mark,” she said during the segment.

That’s upwards of 10,000 RMB (about 1,450 USD), a figure higher than China’s average monthly income of 1,393 USD as of 2021.

The near-simultaneous discourse around trash collection and the ‘Kong Yiji mindset’ have prompted comparisons, concerns, and a completely new iteration of the larger debate over work culture in China.

The ‘Kong Yiji Mindset’

In Lu Xun’s story, Kong Yiji is a self-important scholar who gets his legs broken after stealing books. Both ridiculous and tragic, Kong has a futile fixation on the past.

Set a few years after the fall of the Qing Dynasty, the story starts with him being ridiculed by the working-class customers in the tavern he frequents for continuing to wear his long scholar’s gown, even though he never passed the imperial exam that could have landed him a decent job back in the feudal days.

As The Paper, a Chinese media company based in Shanghai, writes, “[Kong Yiji] would rather steal than do what he considers a menial job just to make money… [This is relatable] in the eyes of some, [who think] their academic qualifications didn’t lead to the job they wanted or deserved.”

The related term, ‘Kong Yiji mindset,’ refers to those who see Kong in themselves as they face the pressures of a job market that can’t keep up with the record-breaking number of college graduates.

Last year, less than half of college students set to graduate in 2022 had received job offers by mid-April; meanwhile, the unemployment rate for all youths aged 16-24 last summer was a staggering 19.9%.

Kong is a sympathetic figure to some recent college graduates whose reality is not living up to expectations.

Rejecting Kong Yiji

Huang, though, represents the opposite of the ‘Kong Yiji mindset.’ In the interview, she said, “I was scared of being looked down upon, but once I got to a certain level of cognition, I realized that wasn’t important. We shouldn’t let our education levels shackle us.”

Many comments under a repost of the BRTV segment on Weibo, China’s top microblogging platform, are variations of “this woman is amazing,” reflecting a generally positive response to Huang’s work.

In some respects, Huang’s embrace of trash collection is similar to Chinese youths’ recent romanticization of the security guard profession. Both are related to the counter-cultural ‘lying flat’ trend that began to sweep China in 2021, wherein younger workers are deciding to opt out of the rat race.

The difference, though, as education scholar Xiong Bingqi points out in a Beijing News article, is that Huang’s work is “strictly a kind of entrepreneurship, which requires a lot of business management thinking, so it should not be simply equated with the stereotyped ‘rag recycling.’”

According to Xiong, Huang isn’t rejecting the whole rat race — just the traditional version of it.

A Structural Failure

Huang may not have many personal detractors, but some are worried about the societal failures that her story hints at.

One person wrote on Weibo, “If we only complete education but fail to create jobs that promote social progress, so that a large number of college graduates do jobs that only require a middle school degree, it means that there is a problem with the overall planning of our society.”

Other netizens are concerned that education itself may one day be seen as superfluous.

“When we were young, we were told to study hard, and when we grew up, we would become astronauts and scientists,” a Weibo user commented. “Now it has become study hard to screw screws, to be a cleaner, to collect junk. It’s not that I look down on those professions, every profession is respectable. But it is strange that the wind is blowing in this direction.”

In recent years, China has been pushing to expand vocational education as a means to solve the surplus of college graduates. However, the transition remains challenging as the stigma around blue-collar jobs lingers.

Cover image via Xiaohongshu