Journalist, New York Times-bestselling author, and media consultant Jeff Yang has been writing about Asian American representation in pop culture for decades. In 1989, Yang and a few others founded A. Magazine, a publication covering Asian American issues and culture. At its peak, it reportedly had a circulation of 200,000, making it the largest Asian-American-focused publication in North America.

“A. Magazine’s whole purpose was to trace the emergence of a distinctive Asian American identity and culture,” Yang told RADII via email. “But back then, we were still so early in this journey that I remember having to scour the world for stories to cover and people to spotlight.”

I knew what I was going to have for breakfast this morning #EverythingEverywhereAllAtOnce pic.twitter.com/7JPXLo10xb

— Jeff Yang 🫶 (@originalspin) February 27, 2023

A lot has changed since then. For one thing, Asian Americans have made massive strides in Hollywood — a journey that Yang chronicles in his upcoming book, The Golden Screen: Movies That Made Asian America. It’s a sprawling history of Asian Americans in film (and of Asian America through film) that will be published by Running Press in October.

“It shows how much our world has changed,” Yang told us. “We went from just trying to find any representation at all to now being asked to talk about our culture and community at the highest level.”

It’s literally the first day announcing this so I know this doesn’t mean much yet but…

— Jeff Yang 🫶 (@originalspin) March 15, 2023

#5 on Amazon’s Movie Reference bestsellers

#2 for Movie Reference new releases

Thank you everyone who’s preordered!https://t.co/303cRwUdT4 pic.twitter.com/EZ5mUedT6I

Composed of essays, film stills, anecdotes, and conversations, The Golden Screen is the first definitive history of Asian American film. For the book, Yang spoke to some of the most recognizable faces in Hollywood, including actors Simu Liu and Ken Jeong. Academy Award-winning actress Michelle Yeoh and director Jon M. Chu wrote the foreword and afterword, respectively.

Films that make an appearance in the book range from The Good Earth (1937), a story about Chinese farmers that was performed almost entirely by white actors in yellowface, to independent comedy Chan is Missing (1982), and Oscar-winning South Korean hit Parasite (2019).

As the existence of The Good Earth proves, the relationship between Asian Americans and Hollywood has long been tumultuous.

When Yang was growing up in the 1980s, there was little representation, and what little there was was often problematic. For example, in the 1984 romcom Sixteen Candles, an Asian exchange student named Long Duk Dong is the primary source of comic relief.

He is sex-crazed, dorky, and struggles to speak English; his entrances are all announced by a gong. Journalist Alison MacAdam wrote that, to some, “he represents one of the most offensive Asian stereotypes Hollywood ever gave America.”

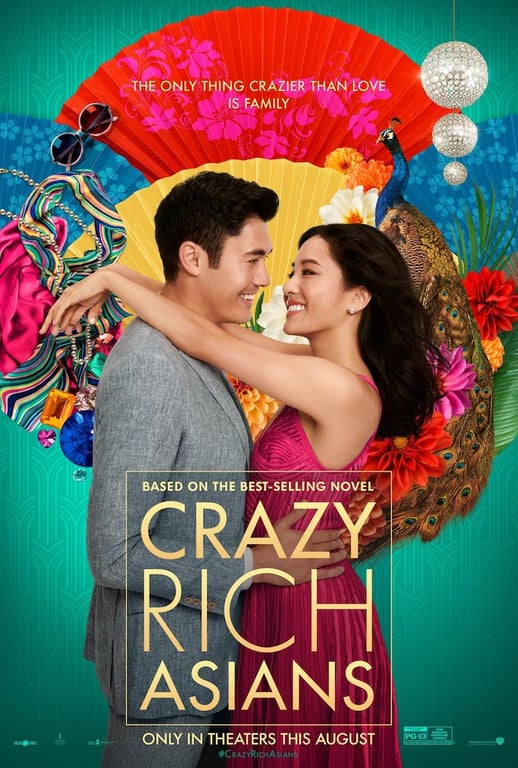

In the intervening decades, though, films like The Joy Luck Club (1993) and Crazy Rich Asians (2018), as well as performers like Yeoh, Liu, and Jeong, among many others (including Yang’s own son Hudson, who starred as Eddie Huang in ABC’s Fresh Off the Boat), have helped the industry along to a watershed moment for Asian Americans.

In March, Everything Everywhere All At Once, a sci-fi dramedy about a Chinese immigrant family, won ‘Best Picture’ at the Oscars, and Yeoh became the first Asian woman to take home the award for ‘Best Actress.’

So I should say I’m at the EEAAO cast and crew #Oscar Watch Party courtesy of the excellent guys of Martial Club, seen here in blurry photo, it has been freakin’ *amazing* so far pic.twitter.com/T7MwfZDqC2

— Jeff Yang 🫶 (@originalspin) March 13, 2023

It feels like the perfect time, then, for a book like The Golden Screen to investigate how Asian Americans got to this point — and where we still have to go from here.

Yang, who has spent his career writing about the Asian American zeitgeist, has seen first-hand how Hollywood moved from Long Duk Dong to the cathartic success of Everything Everywhere All At Once.

Over email, Yang recently discussed his forthcoming book, his life-long coverage of Asian American issues, and much more with RADII. Dive into the interview below.

RADII: First things first — your book The Golden Screen: Movies That Made Asian America is coming out in October. The book is structured as anecdotes, film stills, artwork, and essays. Why did you choose this format?

Jeff Yang: The book talks to dozens of prominent Asian American voices about what it means to have watched these films, how they were changed by them, or how the world around them changed when these works were released.

And it tries to contextualize these changes by looking at them thematically. There are eight chapters, each addressing a different way of looking at Asians on screen: as men and women, as migrants, as families, as heroes and villains, and so on. Within each chapter, the films that have changed the way people see Asians and the way Asians see ourselves are organized chronologically so that you can see the journey over time.

And ‘seeing’ is the operative word. Movies are a visual medium, so we can’t talk about them without showing them. In some cases, we even took films that were pivotal but problematic and ‘reimagined’ them with the help of incredible illustrators — imagining what they might look like if remade with ourselves and our stories at the center rather than at the margins. The hope is that this book is more than just a way of looking back at how we got here; it is also a pointer to where we might go next.

Were you considering the topic of Asian Americans in the film industry before movies like Joy Luck Club or Crazy Rich Asians, or were those catalysts? What got you interested in the history of Asian American film?

JY: Well, I’ve been writing about Asian American pop culture since I started writing, and I was interested in it long before that.

I grew up in an environment where I was surrounded mainly by non-Asians — specifically white non-Asians — and my only real set of positive and aspirational images of people who looked like me came from movies. Chinese movies, to be exact.

In an era where all the heroes didn’t share my face, watching kung fu and wuxia films alongside my parents, uncles, and aunts helped me realize that, after all, America is part of a very big world. And though Asian Americans might be minorities in the U.S. population, we’re a majority of the world and part of a vast global diaspora. So that helped me want to write more about the ways that movies and TV, and images in general, shape our lived reality.

My first real breakthrough as a writer came when I was asked by Jackie Chan to co-write his first autobiography, I Am Jackie Chan, which of course, instantly hit the best-seller lists.

But when we wrote that book, he was still relatively unknown in America — we’d go out in New York and L.A. and no one would recognize him on the streets. Elsewhere in the world, in Africa and Europe and all over Asia, he’d get instantly mobbed.

That reminded me of how parochial America can be in its tastes. Of course, right after the book came out, Rush Hour came out, and everything changed for him here. America ‘discovered’ Jackie Chan, who was already one of the biggest stars in the world.

Could you please give our readers five reasons why people should read The Golden Screen, especially for non-Asian Americans?

JY: I think The Golden Screen is for anyone who wants to immerse themselves in a sea of incredibly interesting and sometimes overlooked movies while also considering how perception shapes reality — what we’re seen as is what we’re treated as, and the consequences can be enormous.

They’re enormous even today: consider how the horrific slurs and memes during the pandemic resulted directly in anti-Asian hatred and violence over the past three years. The Golden Screen is a reminder of how this has occurred across our history, how we need to do better as a society, and a celebration of how, in small ways and big, we’re beginning to do just that.

If you could only pick one film from The Golden Screen, which would you choose and why?

JY: My favorite film of all time is Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express. I’m a romantic at heart and a believer in chance and fate, and I don’t think any film sums up both the frustration and the hopeful thrill of love and infatuation better than Chungking Express did.

Plus, it has some of the greatest Chinese actors working at the time, ones who shaped my adolescence, and I will always watch and rewatch it with joy.

It also reminds me that pop culture’s influence works in all directions — it’s so powerful how American music becomes the soundtrack and thematic driver for a deeply Asian story in that film. As a transplant to California, still thinking about what that migration meant to me, the movie has some very personal moments that still bring tears to my eyes or a smile to my face.

We’ve seen an increase in highly successful Asian American films in the past few years, but not so much on TV (except for Fresh Off the Boat and Bling Empire) — why do you think it’s taking TV time to catch up?

JY: Actually, I have to disagree — there’s never been more Asian and Asian American presence on TV. It’s just that there’s also never been more TV! A lot of it is happening on streaming platforms, which have embraced and elevated overseas works (K-dramas, C-dramas, and more) and put them at the center of their feeds, exposing whole new audiences to stars from Asia.

But also, series like Never Have I Ever, Nora From Queens, Doogie Kamealoha M.D., and Quantum Leap (the latter two were both remade with Asian American leads!), Warrior, and so many more… it’s honestly a boom time for Asians on TV right now, both in shows of our own and as major cast members on shows that don’t have Asian-focused storylines.

We’d like to know more about you and your personal experience. How did the lack of Asian American representation in pop culture as you grew up inform your identity and self-perception?

JY: Well, the movies I grew up with were really quite terrible, by and large. I forgot just how blatantly racist Sixteen Candles was. For example, I had reacted strongly to the character of Long Duk Dong when younger, but seeing how he’s depicted and treated in the present made me conscious of just how much Asians were sub-humanized on screen, even in my teen and young adult years.

And yet, I also realized that Gedde Watanabe’s performance [as Long Duk Dong] was in its own way a triumph — humanizing a subhuman character, pulling empathy out of people where none was intended.

It also made me think of how different the movie would be today: it might put the Asian character at the center and make his arc a love triangle story rather than playing him for racist laughs. How would that change young Asian Americans watching it today, relative to the shame and horror I felt growing up with images like Long Duk Dong?

You’ve been reporting on Asian American issues for years. What are some of the most overlooked or underreported concerns that Asian American communities face?

JY: There’s no question that the biggest issue we face within our Asian American community is the emotional isolation and alienation of many within our immigrant (and non-immigrant) populations. We’ve seen some terrible incidents of violence occur, and they point to how little we focus on mental health in our cultures and how poor the infrastructure is to assist and monitor people who don’t have access to traditional forms of support in terms of family or social services.

As you know, anti-Asian hate is on the rise in the U.S., as well as growing geopolitical tensions between America and China. You said in a 2016 interview with the Asia Society that pop culture is a trailing indicator of society. Does it worry you that Asian American representation in pop culture might backslide at some point?

JY: Oh, that always worries me. But I’m more worried that society itself is on the verge of some ugly convulsions. Here in the U.S., we’ve seen anti-immigrant rhetoric and xenophobia at the highest level of our government in ways that we’ve only seen during wartime in the past. Well, that’s scary. It makes you fear that there are some who nostalgically long for a world where it’s easy to tell friends from enemies just by looking at their faces.

The above interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity

Jeff Yang’s ‘The Golden Screen: Movies That Made Asian America’ will be available for book lovers in October of this year

Cover image designed by Haedi Yue