Note: This article by Bailey Hu was originally published by TechNode. It has been re-posted here with permission.

“Straight man cancer (直男癌)”. “Little fresh meat” (小鲜肉)”. “666“. Sometimes popular slang in Chinese, as with other languages, makes you wonder: which remote corner of the internet was this dredged up from, and what could it possibly mean?

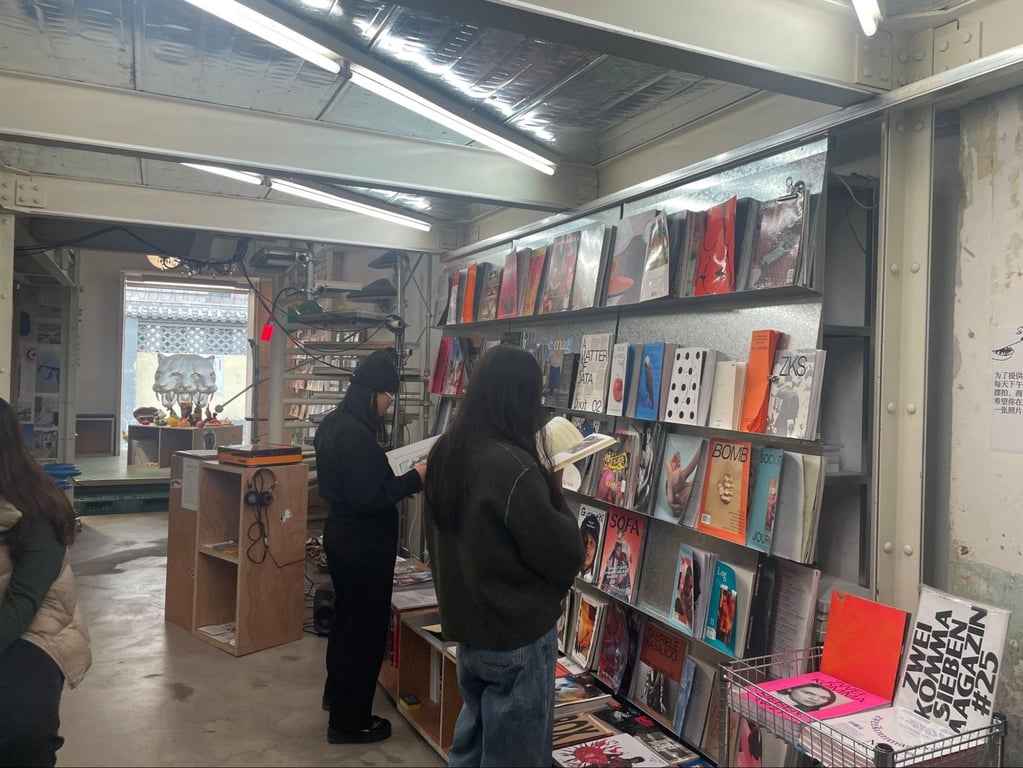

In the case of Chinese internet slang — particularly phrases used by gamers and comic book fans — a team of Peking University researchers decided to find out. The result is The Book That Shatters Shields (破壁书, the authors’ translation), an encyclopaedic tome of 245 “internet culture keywords” that brings a broad swath of online vocabulary into focus.

Tackled in the book’s 500+ pages are words that range from niche to trending. For instance, there’s diaosi (屌丝), popular shorthand for “loser,” and other “border-crossing buzzwords” that bridge online subgroups with the mainstream, says co-author Zheng Xiqing of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

And as it turns out, some of the hottest phrases are being interpreted incorrectly.

“One of the words that gets used pretty randomly and misconstrued is the word called ‘打call.’”

Originally describing a synchronized dance performed by fans at pop idol concerts, 打call has since been adopted as a general phrase of encouragement.

“It’s misunderstood, misused and [has] entered into the public vocabulary recently. Because I think it’s interesting and it’s different from the usual [thing] you tell people – “jiayou [加油, a common cheer] – that’s too plain….”

With factoids like these, The Book That Shatters Shields sheds light on lesser-known online communities that are nevertheless shaping mainstream Chinese culture. We chatted with Zheng about the process of researching terms, the ever-shifting nature of slang, and what popular words like zhai (宅) really mean.

How did you choose your terms?

Because most of [the researchers] are participants of online fan cultures, online communities… [we are] what Henry Jenkins [calls] acafans, “academia fans”: we are both academic researchers and participants of these fan subcultures. We consider ourselves insiders of the fan cultures that we study, so we ourselves choose what keywords are important.

Did the team try to include lots of new Chinese internet slang?

[In the book] we focus more on the lingering things, not the transient phenomena. So especially those [words that] already have established a cultural phenomenon and sustained [it]; we focused more on that. We don’t do “10 hot words in 2016.”

How do relatively unknown online words become mainstream?

Terms migrate and this is how languages work. People pick up terms here and there and they seem interesting. Probably, these words used in subcultures more vividly depict something of a social phenomenon, or people just pick up something that they don’t understand and just use it without other concerns.

And one of the reasons that we have this book is to tell people that some words being used are not originally this meaning.

[For example,] zhai is understood in China recently as somebody [who] stays at home, [who doesn’t] go out. No, it’s not this meaning at all. It’s just obsessive lovers of certain interests and in a subculture sense specifically, zhai should be somebody who loves Japanese anime, manga, this type of cultural products.

Favorite phrases from your research?

[Danmei/耽美] is one of my favorite examples. In China, it’s called danmei, but danmei is not a Chinese word originally, it came from Japan. It’s pronounced “tanbi” in Japanese and it was originally a Japanese translation of the European aestheticism style of Oscar Wilde and that type of writing.

And then it was used to describe certain boys’ love manga [comics depicting gay relationships] of the 1970s and 80s. And then it was then imported into Chinese through Taiwan and they call this danmei, but Japanese no longer call these kinds of writings and manga as tanbi.

So we see culture exchanges and misunderstandings and definition transformations just through this little word.

Was it hard to keep the book current, given how quickly slang changes?

Strangely, no. I don’t think any of the terms in the book are obsolete right now. We started writing this thing in 2015 and it’s already 2018. And I think most of the terms are still buzzwords right now or are still in daily usage.

Related:

“Baizuo” – China’s Term for “Social Justice Warrior” – is Now in Urban DictionaryArticle Mar 30, 2018

“Baizuo” – China’s Term for “Social Justice Warrior” – is Now in Urban DictionaryArticle Mar 30, 2018

What sets the book apart?

One of the reasons I find this book very groundbreaking is because there was no book, no written books or definitions for this subculture phenomenon in Chinese at all. So if you want to know a definition for certain words, you have to go to Wikipedia or even worse, Baidu Baike.

Some of the materials were not written down, and some of this was an oral history, so it’s very good we are also participants of this community, we can write something down that we know that is not known elsewhere.

Any insights on the future of Chinese online lingo?

It’s very complicated and I think another thing that I have to stress here is that [the book is] not supposed to be exhaustive. We’re not examining the whole thing. It’s impossible. It’s too diverse.

And you know the internet, there’s no limit.

Interview dialogue was edited and condensed for clarity. 破壁书 is currently available on Amazon (in Chinese).

—

Image credit: TechNode/Bailey Hu

You might also like:

It’s All “Freestyle” – How Meaningless English Buzzwords Define China’s Pop Culture TrendsArticle Aug 01, 2017

It’s All “Freestyle” – How Meaningless English Buzzwords Define China’s Pop Culture TrendsArticle Aug 01, 2017

Ivanka Trump Tweets “Chinese Proverb”, Confuses Chinese NetizensArticle Jun 12, 2018

Ivanka Trump Tweets “Chinese Proverb”, Confuses Chinese NetizensArticle Jun 12, 2018

“Baizuo” – China’s Term for “Social Justice Warrior” – is Now in Urban DictionaryArticle Mar 30, 2018

“Baizuo” – China’s Term for “Social Justice Warrior” – is Now in Urban DictionaryArticle Mar 30, 2018