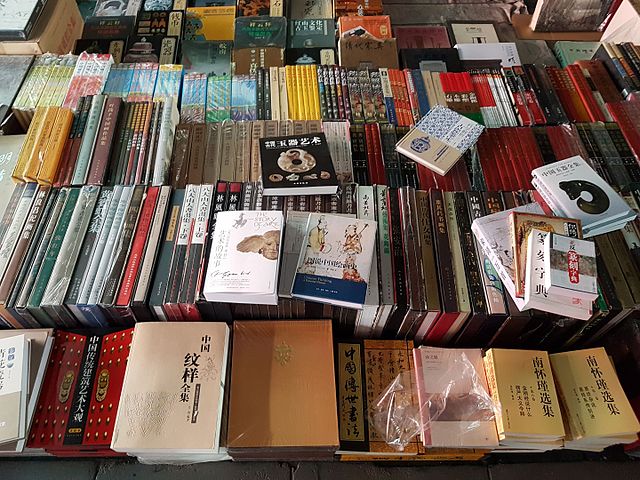

Panjiayuan is Beijing’s most extensive and best-known antique market, regularly attracting orc-like hordes of tourists and locals alike to wander the warren of booths and stalls. All manner of old and made-to-look-old items are on offer here: jade carvings, stone Buddha statues, ancient coins, Chinese Communist Party pins and propaganda posters, replica Korean War medals, and mounds of books.

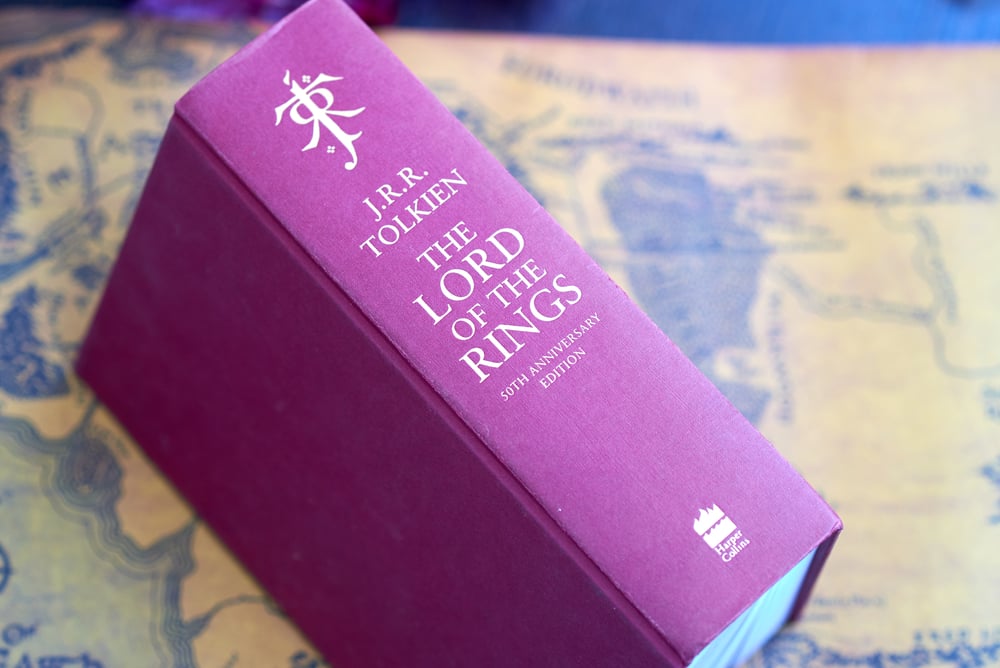

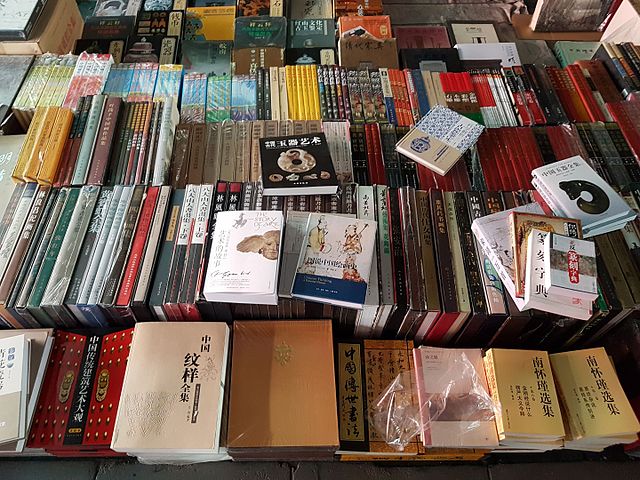

On a brisk autumn day in 2020, I noticed a seemingly out-of-place title while standing at a hawker stand specializing in old Chinese-language books. Among the piles of Chairman Mao’s iconic Little Red Book was The Art of The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien. The English-language and hardcover book, a collection of sketches and maps made by the author, was published in 2015 and compiled by Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull, well-known scholars of the ‘father of high fantasy.’

Tolkien, of course, is famed for The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, among other works, novels set in his fictional land of Middle-earth. His stories feature a diverse array of fantastical beasts and beings, including massive spiders, dragons, elves, dwarves, and the simple and heroic hobbits.

Books at Beijing’s Panjiayuan market. Image via Wikimedia

Despite being a regular at Panjiayuan, it was the first time I’d seen Tolkien’s work for sale there, and the unexpected find led me to ponder: How and when did Tolkien’s work arrive in China, and does China have a Tolkien fanbase as rabid and passionate as that in the West?

What follows is a summary highlighting some of the most insightful information I’ve gleaned since embarking on my quest to understand the impact of Tolkien’s mythology in China.

The Ring Goes East

In a broad sense, fantasy is nothing new in China: In the 16th century, during the Ming Dynasty, the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West was published. The story, which chronicles the adventures of a Buddhist monk who travels to India to recover Buddhist scriptures, features numerous magical beings — most notably the Monkey King, Sun Wukong.

But The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit are different. For one, they are Europe-centric, with the author drawing inspiration from European folklore, fairy tales, religion (primarily Roman Catholicism), and language. His experiences in war-torn Europe during World War I also influenced elements of his Middle-earth legendarium. Characteristics of East Asian folklore, religion (Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, etc.) and language are notably absent from Tolkien’s work, which means that an approachable cultural entry point can be challenging to find for prospective Chinese readers.

Originally published way back in 1954-55, Tolkien’s trilogy was released when the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was mostly closed off to the world. Revolutionary Mao Zedong and the Communist Party of China had risen to power only a half-decade before the release of The Fellowship of the Ring, and land reforms and collectivization were underway. Only a trickle of foreign media made its way into the country at that time, most of it of the ideologically-aligned and Soviet variety.

The greatest hindrance to Tolkien’s masterpieces in China, though, was the lack of a Chinese-language translation of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. This impediment wouldn’t be overcome until 1998, when the Wanxiang and Lianjing publishing companies in Taiwan released two versions of The Lord of the Rings translated into traditional Chinese.

Since then, several more versions of Tolkien’s three-part epic have been translated to both traditional and simplified Chinese characters, along with some of his other stories, including The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Other Verses from the Red Book, Roverandom, Leaf by Niggle, The Silmarillion and, of course, The Hobbit. Many other stories have not been officially translated, though.

Still, many Chinese-language translations of Tolkien’s three-volume epic have suffered due to the lack of cultural context mentioned above.

A thesis paper written in 2000 by a student at Fu Jen Catholic University in Taiwan analyzed the various translation issues in the first Chinese-language versions of The Lord of the Rings published two years earlier. The author, David van der Peet, notes that both versions include a myriad of translation gaffes and fail to convey the original meaning of Tolkien’s text. He attributes these shortcomings to the translators’ lack of knowledge of “the complicated linguistic and cultural backdrop” that frames the trilogy.

Later translations suffered from similar criticisms.

Of the numerous The Lord of the Rings Chinese-language translations, the work of Taiwan resident Teng Jia-wan stands out. Teng first got acquainted with the fantasy trilogy while studying at a British university in the late 1990s, according to a 2018 China Daily profile. She felt so enchanted by the novels that she decided to translate them into Chinese.

Unfortunately, Teng was a little late to the party, and the abovementioned Chinese-language versions of The Lord of the Rings already existed. So, after returning to Taiwan in 1998, she translated The Silmarillion — a collection of myths written by Tolkien — instead. Her version was published in Taiwan in 2002 and spread online in the Chinese mainland.

Teng’s dream to translate and publish a Chinese version of The Lord of the Rings would eventually come true, though: In 2012, she was tapped to translate a new version of the celebrated trilogy along with two other Chinese Tolkien fans she met through online forums. The finished product was published in 2013 and has been hailed by some as the most accurate translation of the story of the quest to destroy the One Ring.

Into the Fires of Fandom

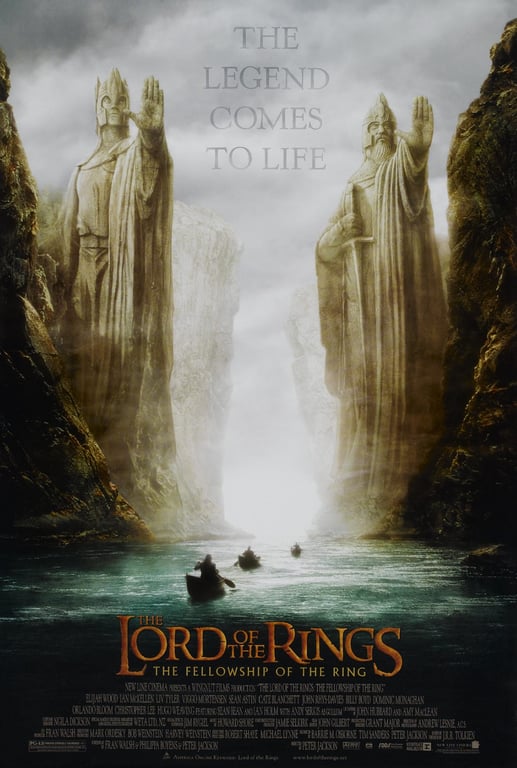

While the success of Peter Jackson’s three-part film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings was practically guaranteed in the Western world, there were no promises it would be a shoo-in blockbuster in the PRC. (If you don’t believe me, look no further than the Star Wars films for an example of popular Western media that has consistently bombed on the Chinese mainland.)

Despite the obstacles to the success of the story of Frodo and the Ring of Power in the Chinese market, Jackson’s films would find a reason to celebrate in China.

Peter Jackson in 2012. Image via Wikimedia

Chicago-based physicist and writer Dr. Yangyang Cheng recounted the fanfare around the launch of The Fellowship of the Ring in China in an essay published in The China Project (formerly SupChina). Dr. Cheng grew up in a medium-sized city in Central China and was first introduced to Tolkien’s work when her mother brought home a Chinese-language collection of classic Western stories. Her favorites were the abridged versions of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

Asked about the hype for the film adaptation of Fellowship, Dr. Cheng told me via email that “posters and billboards for the movies were everywhere in the city and my classmates and I talked about it often at school.”

In her essay, she also notes that Chinese-language adaptations of the books were soon prominently featured in every bookstore, and China’s once-ubiquitous roadside DVD hawkers began offering copies of Jackson’s films with “dubious licensing.”

In 2004, the final film in Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Return of the King, became the top film at the Chinese box office — a massive achievement. A decade later, when the filmmaker’s comparatively lackluster conclusion to the three-part film adaptation of The Hobbit hit silver screens, it was the Chinese market that helped it rake in the dragon’s hoard.

On its opening weekend in China, The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies brought in a record-breaking 49.5 million USD. According to a Vanity Fair article from early 2015:

“Even though it did pretty well domestically, the Hobbit trilogy didn’t end up being quite the box office titan Lord of the Rings was back in the pre-Marvel era of 2003. That is, until today. The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies premiered in China this weekend to a record-breaking 49.5 million USD, bringing its worldwide revenue to 866.5 million USD. Even greedy Smaug might be happy with that.”

From no Tolkien to translated Tolkien to Jackson’s impressive cinematic adaptations, The Lord of the Rings found its way into China’s public consciousness. The fantasy novels and films have proven so popular in the country that — believe it or not — a company constructed a One Ring-inspired skyscraper in 2019 in Southwest China’s Chongqing municipality.

Prime Time for Another Adventure

Amazon’s massive-budget TV series set in Middle-earth’s Second Age, The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, arrived on the company’s Amazon Prime streaming platform on September 1 in North America. Over the past few days, no shortage of ink has been spilled by those reviewers lucky enough to get a sneak peek of the highly anticipated show.

As you’d expect, there are a variety of opinions being shared. Columnist Rebecca Nicholson from The Guardian gave the show four out of five stars and praised its impressive visuals, while an Entertainment Weekly critic called it “kind of a catastrophe.” (For more opinions of the show, see The New York Times’ roundup of TV critic reviews.)

With the airing of divergent opinions of The Rings of Power in the international press, I’ve wondered how the Tolkien-inspired Amazon series will be received in China.

“I think The Lord of the Rings has a really great reputation in China. I feel like it is honestly one of those works of Western literature that is most accessible to the average Chinese person. I think [the Amazon Prime adaptation] will do well,” Bryan Grogan, RADII’s former culture editor, previously told me.

The super-high-budget show will presumably benefit from Chinese audiences’ familiarity with Tolkien’s literature and Jackson’s films, and the bump in popularity the fantasy genre received in the country thanks to HBO’s mega-hit series Game of Thrones.

Game of Thrones was must-watch television for many people in China, and pirated episodes dropped on Chinese streaming sites within hours of appearing on HBO.

Considerable online chatter preceded and followed each new Game of Thrones episode (in the later seasons, anyway) on the Chinese microblogging platform Weibo. Memorably, one creative netizen released a viral series of Photoshopped images featuring characters from Westeros as Chinese street vendors and New Year’s travelers.

A Game of Thrones fan in China reimagined characters from the show as street food vendors in a viral photo series. Image via Weibo

On the morning of September 2 in China, a hashtag for The Rings of Power had generated almost 67 million views on Weibo, and most commenters seem generally excited about the series’ arrival.

“Middle-earth is calling me; I have hope for life now,” wrote one Weibo user. Another praised Welsh actor Morfydd Clark, who plays royal elf Galadriel in the series: “The powerful beauty of Morfydd Clark completely takes me. I can’t think of an actor more suitable for this role than she is.”

“Although Harry Potter may have more fans in China, The Lord of the Rings series is very popular among Chinese people, and I think the [new] series will be well received in China,” said a self-professed, Beijing-based Tolkien fanatic surnamed Dai.

At the time of writing, no official release for The Rings of Power has been announced for the Chinese mainland, meaning Amazon likely hasn’t secured a domestic streaming partner (yet…). However, based on past precedent, I think it’s safe to assume that pirated episodes will quickly find their way onto the Chinese internet for PRC-based fans to enjoy.

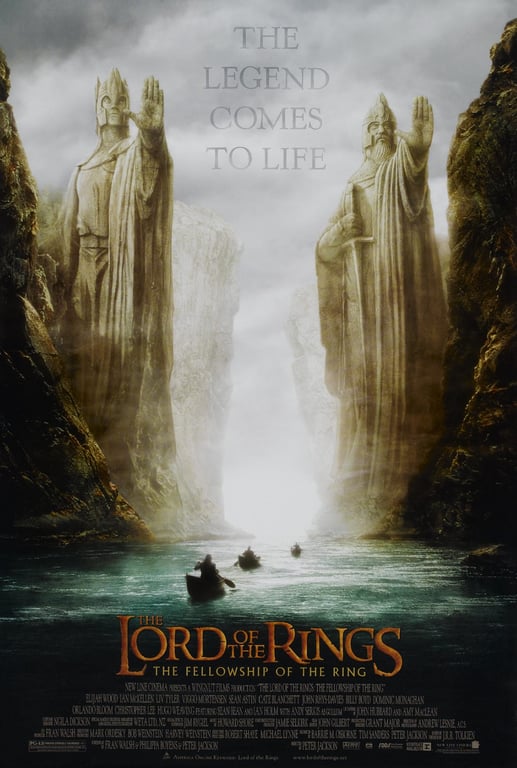

Cover image via IMDb