Music is obviously a big thing for us here at RADII, and lately we’ve been struggling under the algorithmically mandated weight of hashing out a “Best Albums of the Decade” list. How many do we choose? 10? 20? A thousand? What genres? Are genres still a thing? It was daunting.

So we’re copping out and instead shining a wider light on labels: the curators, diehard self-publishers, DIY cassette dubbers, taste-makers, scene-builders and community sustainers who gave underground Chinese music a whole 2010s vibe.

The Curators

For many, a record label is an imprimatur of a specific taste, a guarantor of quality, a signal of “if you liked that, you might also like…” In the world of Chinese indie, no label has done this better over the last 10 years than Beijing-based Maybe Mars.

During its first few years of existence, from 2007-2009, the label experimented across genre lines, releasing booze-soaked punk from Joyside, cerebral post-punk missives from Snapline and P.K.14, harder-edged punk/hardcore from Wuhan’s SMZB and Tongzhou’s Demerit, and difficult-to-pin rock & folk from outlier acts like Ourself Beside Me and Xiao He.

The first Maybe Mars release of the new decade was, appropriately, the debut of Dear Eloise, the duo of vocalist Sun Xia and her husband, P.K.14 frontman Yang Haisong, also the head of Maybe Mars today. The first half of the decade saw the label slowly evolve in the direction of a young generation of bands, like Birdstriking and Chui Wan, who were directly influenced by the “scene elders” of their immediate forebears, usually transmitted in person at Maybe Mars’s in-house venue, D-22.

Especially over the last few years, Yang’s stewardship of the label has dialed in the Maybe Mars-ness of it, and you have a fairly good idea of what you’re getting with a new release today: something jagged, intellectual, visceral, angular; something that we can now confidently call a specifically Chinese strain of post-punk. Maybe Mars has maintained its brand integrity after it was acquired by Taihe Music in 2017, a phenomenon reflecting the late-2010s trend of a few major companies at the top (Taihe and Modern Sky within the music industry, with tech co’s Tencent, NetEase, and even TikTok parent ByteDance circling around an even higher tier of the food chain) absorbing everything swimming below them.

Compared to Beijing, Shanghai has long been seen as a flashy commercial center with no cultural soul. But in the last decade the city has grown into one of the most interesting hubs for original, boundary-pushing electronic music in the world — with a series of features in the likes of DJMag and Dazed (the latter by our own Josh Feola) adding weight to these credentials.

The label at the forefront of representing this new sound is SVBKVLT. Having begun as a cassette imprint in 2013, the label has since become the go-to for anyone looking to dive into the Shanghai electronic music scene thanks to a carefully-curated slate of digital and vinyl releases from the likes of 33EMYBW, Gooooose, Hyph11e, and Swimful.

Founded by Mancunian Gareth Williams, SVBKVLT has provided a path to release for the artists who have been drawn to the clubs that he has run in the city, first legendary (and literally) underground venue The Shelter, and now ALL. But those venues, and the label, have also inspired a new generation of young Chinese artists to build their own infrastructures, with traces of The Shelter and SVBKVLT’s DNA in the likes of Hangzhou’s Loopy, Shenzhen’s Oil, and Shanghai collective Genome, making their influence all the more far-reaching.

See also:

- D Force / Merrie / Little Soul: Honorable mention here to these three labels by the same group of people. D Force started as an offshoot of social network/streaming service Douban Music, an initiative by its true-blue underground music nerd staff to curate some of the most interesting sounds coming out of China. To that end they released some indisputable 2010s classics, like Hai Qing’s The Flesh and DOC’s Northern Electric Shadow. Most of the Douban Music staff split after Tencent invested heavily in Douban FM earlier this year, and have since regrouped under the banner of two sub-labels: Merrie (which released 33EMYBW’s stellar 2019 EP Dong2), and Little Soul (which released Hai Qing’s latest).

- METAL: On the genre level, Chinese metal has a handful of stalwart labels who cumulatively put out about a hundred albums this decade. Learn more about the lay of the land here, or head straight to the Bandcamp pages of Pest Productions, Dying Art Productions, and Stress Hormones Records for a direct fix.

DIY or Die

Other people expect record labels to, you know, put out records. Albums you can hold with both hands, physical music media. Genjing Records, which launched in October 2009, led the charge of a vinyl resurgence among underground music lovers across China. Starting with a handful of hardcore and punk releases reflecting the personal proclivities of label founder Nevin Domer, Genjing has gone on two issue over 50 slabs of black plastic, most of them split 7″s pairing a Chinese band with a foreign counterpart with the aim of establishing cross-cultural and inter-scene dialogue among diehard DIY pockets around the globe.

More on Genjing:

B-side China Podcast: Genjing Jukebox w/ Nevin DomerArticle Dec 08, 2017

B-side China Podcast: Genjing Jukebox w/ Nevin DomerArticle Dec 08, 2017

So far, so Beijing- and Shanghai-focused for this list. But one of the key defining factors for alternative Chinese music in the 2010s was its geographical diversity, as a whole host of labels and collectives cropped up across the country to support DIY scenes in their regions.

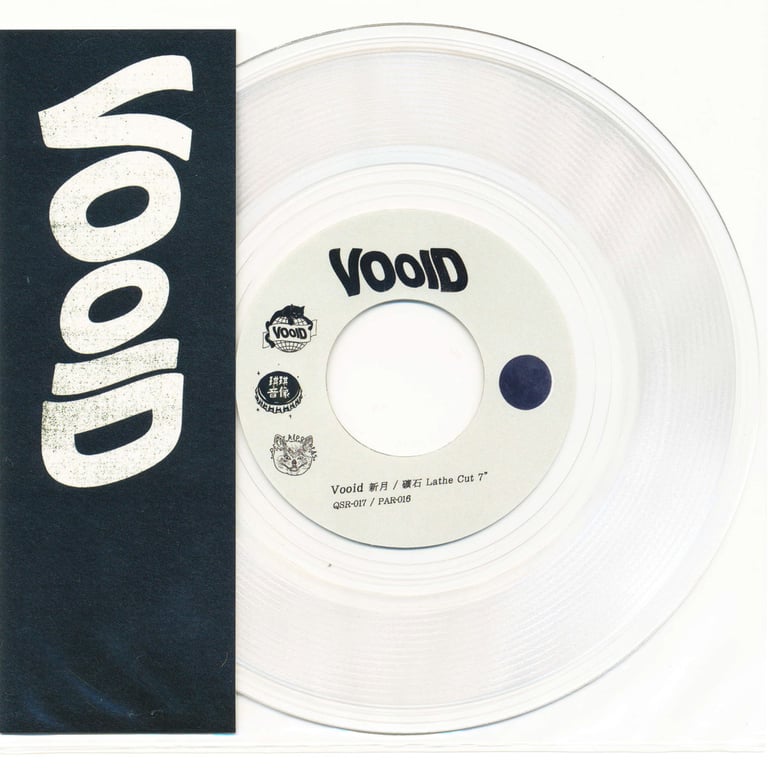

One of the most inspiring forces in this movement has been Qiii Snacks. Officially launched in 2015 but with roots going back further via related progenitor Full Label, Qiii Snacks began by focusing only on bands from their native Guangzhou, before broadening that view out to southeastern China’s Pearl River Delta, and eventually the entire country (and even internationally). Whether it’s been through their lathe-cut vinyl releases, cassettes, or zines, there’s always been a strong DIY ethic running through Qiii’s work, something they’ve helped imbue other regions with through an array of collaborations.

And in case you need another reason to check out their discography, they also have one of the most eclectic rosters when it comes to artist names of any label on this list, with releases by the likes of Nein or Gas Mus, SmellyHoover, Foster Parents, Cheesemind, Curse League, The 尺口MP, and lots more besides.

More on Qiii Snacks:

Guangzhou’s Qiii Snacks Records is Capturing the Sound of Southeastern ChinaArticle May 22, 2018

Guangzhou’s Qiii Snacks Records is Capturing the Sound of Southeastern ChinaArticle May 22, 2018

A newer, but notably impactful DIY collective on the Chinese underground music scene is Eating Music. Founded by Cookie Zhang in January 2018, the label has put a focus on community-building events and releases that have skipped across genres, yet still felt part of some cohesive whole. In between jazz, hip hop, and lo-fi beat records, Eating Music has put out several collaborative compilation albums and hosted two “camps” with established musicians mentoring younger artists hoping to hone their craft.

Perhaps unsurprising then that Zhang nurtures ambitions of Eating Music being China’s answer to Stones Throw, the renowned Peanut Butter Wolf-founded label behind releases from J Dilla, Madlib, Dâm Funk and more.

More on Eating Music:

Artist, Entrepreneur, and Vinyl Visionary Cookie Zhang Wants to Change China’s Taste in MusicArticle Sep 11, 2018

Artist, Entrepreneur, and Vinyl Visionary Cookie Zhang Wants to Change China’s Taste in MusicArticle Sep 11, 2018

See also:

- Rose Mansion Analog: This list is somewhat post-2015-heavy, reflecting an uptick in DIY labels across the country around that year. But Beijing label Rose Mansion — house organ of The Offset: Spectacles, Hot & Cold, Soviet Pop and Luxinpei — kickstarted a DIY cassette-worshipping renaissance around the beginning of the decade, working in lockstep with the Zoomin’ Night contingent (see below). The Rose Mansion spirit survives in the form of 工工工, a band comprised of two of the label’s founders, who released one of our favorite albums of 2019.

- Spacefruity Records: The small but crucial output of Spacefruity deserves a nod. Born as a label offshoot of Beijing lo-fi/experimental music redoubt Fruityspace, Spacefruity has lovingly put some of China’s grimiest, grungiest and weirdest stripped-down rock’n’roll to wax and tape over the last several years. Especially recommend the 2018 albums by Dolphy Kick Bebop from Hangzhou and Ya Ting Tian from Yiwu.

- Groove Bunny: A little quiet of late, but still well worth a mention is this hip hop, funk, and electronic-focused label based out of Jinhua, a city of about 6 million people that you’ve never heard of. Headed up by Endy Chen, who together with Eating Music is the driving force behind wax-proselytizing brand Daily Vinyl, Groove Bunny’s back catalogue spans from Cantonese boom bap to beats that are “an embodiment of sage life, a trip to Burger King, and a reflection on modern China.”

- SJ Records: This Shanghai and Hangzhou-based label — named after one of the region’s favorite dumpling types, the shengjian — has built up a discography of more than a dozen releases since founding in 2017, mostly with a shoegazey bent and sometimes in collaboration with Qiii Snacks. Surf-rockers Kirin Trio and lo-fi indie-pop outfit Zoo Gazer are the main acts in their stable.

The Experiments

“Experimental music,” broadly defined, has always depended upon tightly-knit local scenes and immensely dedicated labels to keep the experiment going. No one’s in it for the money. Despite the overall effect the internet’s had in lowering the barrier to entry for maintaining a net-label, some veterans on China’s avant-garde music scene have actually noticed a decline in such labels over the last decade.

As Wang Changcun, one half of the play rec label, noted in a recent interview: “Ten-plus years ago it seemed that everyone making [experimental] music had their own label, and was self-releasing their music… Over time, all of these labels and the people behind them slowly faded away. Maybe Xu Cheng and I are still too stubborn, so we decided to start our own.”

Though fairly new, play rec has been one of our favorite labels to enter this fray and consistently release bold experiments on the more nerdy, hackery, electronics/computer/code-oriented end of the toolkit.

Zoomin’ Night began life in August 2009 as a weekly experimental music showcase at D-22, the Beijing hotbed that kickstarted the careers of Chinese indie rock royalty like Hedgehog and Carsick Cars. Named after a P.K.14 song, Zoomin’ and its dauntless ringleader, Zhu Wenbo, intentionally cherrypicked the most difficult and challenging, sharpest edges of that small cauldron of far-out sounds and shaped it into a coherent scene-within-a-scene, and a weekly that would last for about six years.

When D-22 closed in January 2012, it was followed up by XP, a club basically opened with the mandate to make every night a Zoomin’ Night. XP kept the lights on until summer 2015, after which point Zoomin’ Night lost its physical home and morphed into a label that to this day steadily releases the rarefied abstractions that have been borne over the previous years of trial and error.

See also:

- Sub Jam: Where the previous decade in Beijing experimental music was largely defined by Yan Jun, his weekly series Waterland Kwanyin, and this label, since 2010 Yan has faded into the background somewhat, preferring to throw low-key, intimate gigs in his apartment. He collaborates frequently with members of the Zoomin’ Night cohort, however, and still maintains a trickle of releases on Sub Jam, which originated as a rock label in 2001.

- NOJIJI: This acephalic, kinda-Beijing-kinda-Shandong-based roving noise coalition has always been difficult to conceive of as a “label.” In 2010 they were collected in the venue they ran on the far outskirts of Beijing, Raying Temple, a converted fish hatchery, but they got booted out of there not long after and have since piled in to a large van for improvised, public performances in forests and open plains across rural China.

- Maybe Noise: What started as a short-lived, experimental offshoot of Maybe Mars last decade has returned in recent years as a label laser-focused on contemporary composition, strictly calibrated by the trio of Zhang Shouwang (Carsick Cars), Yan Yulong (Chui Wan), and Sheng Jie (gogoj). Their catalog to date is quite small, but aesthetically brilliant, thanks to the design work of Shanghai-based Wu Qingyu.

- Badhead: Informed readers might wonder about the lack of some of the biggies on this list, like Modern Sky. They’re more of a festival brand these days, but credit where it’s due: over the last few years we’ve been happy to see the resuscitation of Badhead, an experimental offshoot of Modern Sky initially launched in 1997. Since rebooting in 2016, Badhead has put out some pretty great releases from Red Scarf in Shenzhen, guitar god Li Jianhong, and FEN, an all-star teamup featuring Yan Jun, Otomo Yoshihide, Ryu Hankil, and Yuen Chee Wai.

The Scene-Builders

Do Hits, co-founded in 2011 by Sulumi, Billy Starman, Guzz, and Howie Lee, started out incongruously enough as a monthly party at School Bar, ground zero for Beijing’s punk scene. Once Shanghai dance club Dada opened its Beijing location in October 2012, Do Hits found a more appropriate home, and proceeded to establish a style that’s still a touchstone for many young producers and DJs around the country today.

As a label, Do Hits was invested in scene-building from the beginning. Its first three releases were a series of compilations, and some of its more memorable have been annual Zodiac-themed comps remixing vintage Mandopop and holiday classics for Chinese New Year. Though quiet of late, and eclipsed somewhat by the individual successes of members Howie Lee and Guzz, Do Hits remains a template in the DNA of Beijing’s club culture and the labels that it has spawned since, like S!LK and the soon-to-launch Out of Fashion Boys.

As mentioned above, the blueprint provided by label SVBKVLT and venue ALL has had a ripple effect on scenes around the country over the last few years. Few have organized into as distinct a local flavor as FunctionLab out of Hangzhou. Though only an hour from Shanghai by high-speed rail, Hangzhou, a large and prosperous but culturally conservative city, lacks many nightlife options. Into this void has loudly roared the FunctionLab set, largely composed of students and graduates from the progressive China Academy of Art. Frequently crossing antennae with likeminded souls in Shanghai, such as the Genome collective, FunctionLab has been one of the most exciting new labels to crop up on the Chinese scene/internet of late.

More on Hangzhou:

CITY MIX: Something in the Hangzhou WaterArticle Aug 14, 2018

CITY MIX: Something in the Hangzhou WaterArticle Aug 14, 2018

See also:

- Wild Records: Launched in 2015 as the house label of long-running Wuhan rock’n’roll venue VOX, Wild Records has maintained a steady output of bands from the region, most notably big-in-Japan emo rockers Chinese Football.

- RAN Music: While the edgier and more avant-garde frontiers of club music have tended to get the most ink lately, Beijing-based label RAN Music has been holding it down in the solid, 4/4, house and techno pocket since 2015. Launched by Xinjiang-born producer Shen Lijia, RAN has built a strong scene in Beijing and, through offshoot imprints like Ran Rad, created a platform of exchange between China and kindred clubgoers in Germany and elsewhere in Europe.

The Rap Boom

The History of Rap in China, Part 2: Hip Hop Goes Mainstream (2010-2019)From humble origins as a niche pastime in constant conflict with the authorities, hip hop rises to become a mainstream art (and industry)Article Feb 08, 2019

The History of Rap in China, Part 2: Hip Hop Goes Mainstream (2010-2019)From humble origins as a niche pastime in constant conflict with the authorities, hip hop rises to become a mainstream art (and industry)Article Feb 08, 2019

When it comes to hip hop labels, things get a bit complicated. In the early days of hip hop in China, rap lovers could only find some scattered, “free” beats online to practice rapping along with. Most releases were mixtapes shared online; very few rappers got real label backing to produce an album, like Yin Ts’ang’s debut on Scream Records. Even in Noisey’s 2017 documentary The Rise of Trap in Southwest China, we see Higher Brothers and GO$H making tracks from their home studios, which are rather shabby.

The Chinese word for “record label” is changpai (厂牌), which literally means “factory brand.” So the question for hip hop becomes: can changpai only describe a traditional record label, or can we expand the meaning to cover crews?

Some longstanding Chinese rap “brands,” like CHEE Production Records in Guangzhou, Pact‘s NOUS Underground (N/U) in Xi’an, C-Block and Sio’s Sup Music in Changsha, MC Guang‘s Free-Out in Nanjing, and HHH (before they disbanded this year) started as rap crews, then transformed into independent record labels. Following the surprise success of The Rap of China in 2017, these crews-turned-labels have not only attracted new blood to their ranks, but also been able to invest in producers and professional promotion and marketing teams.

Some labels are only established to serve certain crews, or by the musicians themselves, like Purple Soul’s Undaloop, Dragon Well from Beijing, and All That Records by AR.

Chinese Rap Wrap: AR Puts Clout Rappers on Blast with “Pop Rap”“Just sing Chinese like it’s English / Then add some bad English in the Chinese bars / They’re made for foreigners so it doesn’t matter”Article Dec 04, 2019

Chinese Rap Wrap: AR Puts Clout Rappers on Blast with “Pop Rap”“Just sing Chinese like it’s English / Then add some bad English in the Chinese bars / They’re made for foreigners so it doesn’t matter”Article Dec 04, 2019

Quite a few crews/labels that have cropped up in recent years, like Walking Dead, Cloudy Tunnel and Seven Gurus, are made up of members based in different cities, or even different countries. In those cases, the concept of “record label” is far more abstract, rather than a company with a specific working place or point of origin.

A few more professional hip hop labels have appeared over the past two years, including AFSC, which shares the same mother company as AYO! Music Festival and signed Pharaoh, Toy Wang, Lil Jet, PAVEL and crew HAS. Fat Shady and entertainment company Show City Times co-founded No.4 Music, which has signed Wang Yitai, Pact, Cream D, BB-Eight and Lil Castle$. And WR/OC, based in Chengdu, brought their acts NINEONE# and Gen-Z rapper lows0n to SXSW last year.

Some bigger, more entrenched players have also entered the game over the last two years. We’ve reported on a lot of rappers signing with MDSK — Modern Sky’s hip hop sub-label, established in 2017 — including Tizzy T, Vinida, Young Jack, BooM, OB03, Saber and many more.

Mintone Records, a Chengdu-based, actual record label that has signed talents including Cee, Lu1 and Dizkar, has been going since 2009, and recently became affiliated with music giant Taihe. The same goes for GVO (Good Vibes Only), another urban music label from Chengdu established last year.

Overseas Undergrounds

While 88rising has been the most visible brand promoting Asian music abroad in recent years, Eternal Dragonz has been our preferred actual-label creating a pan-continental, diasporic, artist-focused conception of “Asian music” in the 2010s.

Sound Between Worlds: Eternal Dragonz InterviewArticle May 23, 2018

Sound Between Worlds: Eternal Dragonz InterviewArticle May 23, 2018

Though admittedly not a “China thing,” Eternal Dragonz has worked with some artists we know and love at RADII, like Kelvin T of Hong Kong label/crew Absurd TRAX, Taipei-born, Shanghai-based Scintii, Do Hits affiliate W.Y. Huang, London visual artist and composer Lawrence Lek, and UnderU label head Sonia Calico. With a decentralized structure and outposts in Australia, the US, and Taiwan, Eternal Dragonz provides a globe’s-eye perspective on some of the undercurrents from China that we report on, informing on how they fit in to a larger geographical and cultural picture.

WV Sorcerer, launched in France in 2015 by Nanjing-born metal/doom/drone aficionado Shen Ruotan (aka ruò tán), could fit in several categories on this list. It’s carefully curated, identifying a common thread connecting the guitar improvisations of Li Jianhong, sax freakouts of Red Scarf’s Lao Dan, Kazakh-inflected dark industrial folk of Mamer and IZ, purist black metal of Nanchang’s Be Persecuted, blown-speaker club shredders of Zaliva-D, ritualistic drone dirges of Taipei’s Scattered Purgatory, and a host of similarly attuned solo and group projects from ruò tán’s adopted home in Europe.

Related:

Club Seen: The8Immortals Blends Classical Art with Radical CountercultureClassical tradition steeped in performative ritual — Qian Geng draws on Tang dynasty poetry and the folk traditions of northeast China in his provocative calligraphic paintingsArticle Oct 31, 2019

Club Seen: The8Immortals Blends Classical Art with Radical CountercultureClassical tradition steeped in performative ritual — Qian Geng draws on Tang dynasty poetry and the folk traditions of northeast China in his provocative calligraphic paintingsArticle Oct 31, 2019

The operation is DIY to the bone, often coming with handmade pins and patches in odd editions numbering fewer than 50. While not specifically focused on a certain local “scene,” ruò tán has worked tirelessly throughout the label’s existence to promote tours for Chinese and Taiwanese artists in Europe, and vice versa, most recently completing a lap of China in 2018 with Scattered Purgatory and Beijing experimental scene legend Wang Ziheng.

See also:

- Chinabot: Despite the name, not really China-focused, but that’s kind of the point. If China’s economic rise is helping to precipitate what one might call the Han-ification of “Asian culture,” Chinabot is providing an antidote, releasing music from across South/East Asia and regularly organizing events in label-runner Saphy Vong’s home base of London with like-minded groups like Eastern Margins.

- Danse Noir: Co-founded in 2013 by Swiss producer (and frequent Asian Dope Boys collaborator) Aïsha Devi, Danse Noir has put out some very interesting releases for a few China-adjacent artists on our radar, including Berlin-based artist bod [包家巷] and Taiwanese producer Meuko Meuko.

- Zoom Lens: This LA-based label has been issuing “emotive electronic post-pop” since 2012, but only really caught our attention this year with the release of Alex Wang’s brilliant, brittle concept album, 0%. Dig in to that one here, and, to end this list on an unsettling note of dystopian futurism, learn more about the bleak visual aesthetics that animate Wang’s sonic worldview via RADII’s recent interview with 3D artist chillchill.

—

Contributions from: Josh Feola, Jake Newby, Fan Shuhong